Everett Gee Jackson (1900-1995), the renowned American painter, illustrator and art educator, lived at Lake Chapala, apart from some short breaks, from 1923 to 1926 (and returned there in 1950 and 1968). Jackson loved Mexico and during his first visit to Chapala he became intimately acquainted with the artistic creativity of Mexico’s ancient pre-Columbian civilizations, later teaching and writing on the subject.

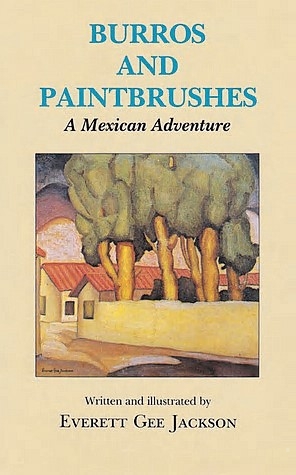

Unlike so many other early foreign visiting artists who have left very little trace of their presence, Jackson wrote entertaining accounts of his experiences in Chapala and Ajijic in his two memoirs —Burros and Paintbrushes, A Mexican Adventure (1985) and It’s a Long Road to Comondú (1987), both published by Texas A&M University Press. Both memoirs are informative and beautifully illustrated.

Given the wealth of available material on Jackson’s life and art, this post will focus on the personal and wider significance of his earliest extended trip to Lake Chapala.

Cover painting is “Street in Ajijic”, ca 1924

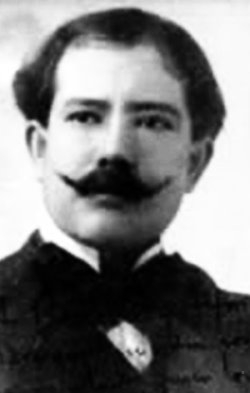

Jackson was born in Mexia, Texas, on 8 October 1900. He enrolled at Texas A&M to study architecture but was persuaded by one of his instructors that his true talents lay in art. In 1921 Jackson moved to Chicago to study at the Art Institute where impressionism was in vogue. At the end of the following year he eschewed another Chicago winter in favor of completing his art studies at the San Diego Academy of Art in sunnier California. He eventually completed a B.A. degree from San Diego State College (now San Diego State University) in 1929 and a Masters degree in art history from the University of Southern California in 1934.

As an educator, Jackson taught and directed the art department at San Diego State University (1930-1963) and was a visiting professor at the University of Costa Rica (1962).

Prior to his first visit to Chapala in 1923, Jackson had already undertaken a brief foray into Mexico, traveling just across the border from Texas into Coahuila with Lowell D. Houser (1902-1971), a friend from the Art Institute of Chicago.

In summer 1923, Jackson and “Lowelito” (Houser) ventured further into Mexico, to the city of Guadalajara. As Jackson tells the story in Burros and Paintbrushes, A Mexican Adventure, they had been there about a month when they heard about “a wonderful lake” from “an old tramp, an American.” On the spur of the moment they took a train to Chapala and loved what they saw:

“We walked from the railroad depot, which was on the edge of the great silvery lake, down into the village with its red-tile-roofed houses. All the little houses that lined the streets were painted in pale pastel colors, and most of the men we met in the streets were dressed in white and had red sashes around their waists and wide-brimmed hats on their heads. The women all wore shawls, or rebozos, over their heads and shoulders. Soon we came to the central plaza, which had a little blue bandstand in the middle. Walking east from the plaza, we found, in the very first block, a house for rent. A boy on a bicycle told us that it had just been vacated. He said an English writer had been living there, and had only recently moved away.”

Jackson and Lowelito had been renting the house for several months before they realized that the English writer was D. H. Lawrence (who left Chapala in mid-July). The two artists had few distractions in Chapala. According to Jackson, the train at that time only ran twice a week, and the main hotel was the Mólgora (formerly the Arzapalo) which faced the lake.

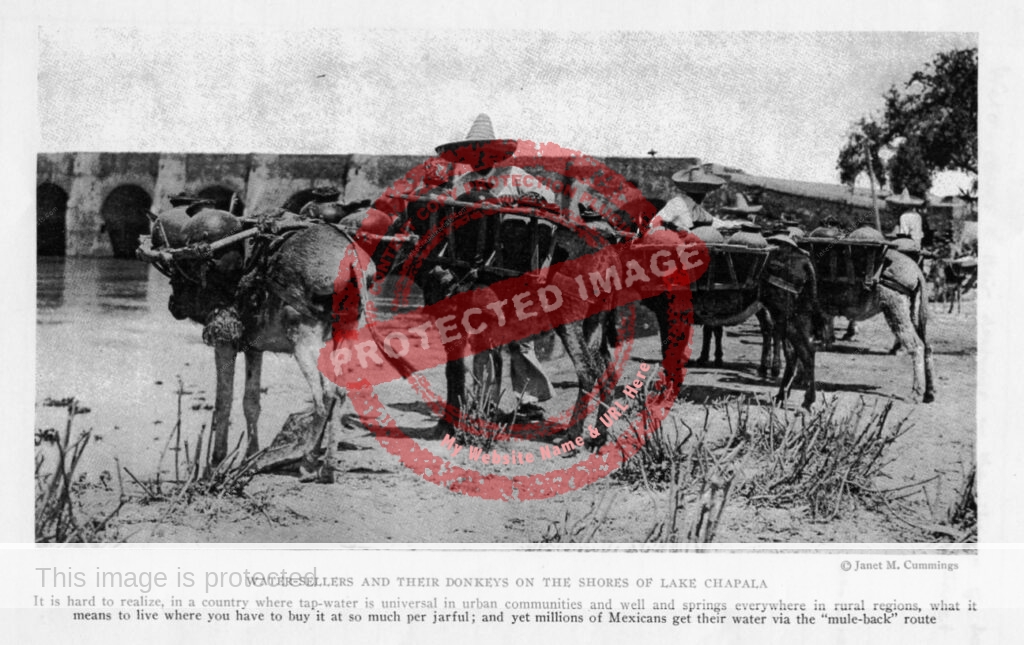

“We were both eager to get to work. We had come to Chapala to draw and paint what we saw, and what we were seeing around us was a visual world of magic: bright sunshine and blue shadows up and down the streets, red tile roofs and roofs made of yellow thatch, banana trees waving above the red tile roofs, bougainvillaea of brilliant color hanging over old walls, the gray expanse of the lake, and a sky in which floated mountainous clouds. Finally, there were the beautiful people, in clothes of all colors-beautiful, happy, smiling, friendly people-and donkeys, horses, cows, hogs, and dogs of all sizes, colors, and shapes.”

Jackson and Houser were among the earliest American artists to paint for any length of time at Lake Chapala and Ajijic, though they were not the first, given that the Chicago artist Richard Robbins and Donald Cecil Totten (1903-1967), among others, had painted Lake Chapala before this. So, too, had many artists of European origin. Mexico, though, exerted a much more powerful influence over Jackson’s subsequent art than it did over any of these earlier visitors.

Jackson and Houser stayed in Chapala until the summer of 1925 when they decided to move to Guanajuato to experience a different side of Mexico. En route, they stopped off in Mexico City to view some of the famous Mexican murals, by Diego Rivera and others, that they had heard so much about.

After a few months in Guanajuato, the two young artists briefly parted ways. While Jackson went back to El Paso to meet his girlfriend, Eileen Dwyer, face-to-face for the first time (following a lengthy correspondence), Lowelito returned to Chapala, where he happened to meet the well-connected young author and art critic Anita Brenner (1905-1974). (This chance encounter led to Houser being invited a couple of years later to join a trip to Mayan ruins in Yucatán as an illustrator. It also led to Jackson and his wife becoming close friends with Brenner after they moved to Mexico City in November 1926.)

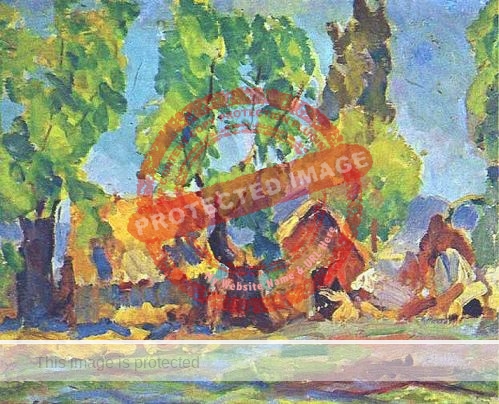

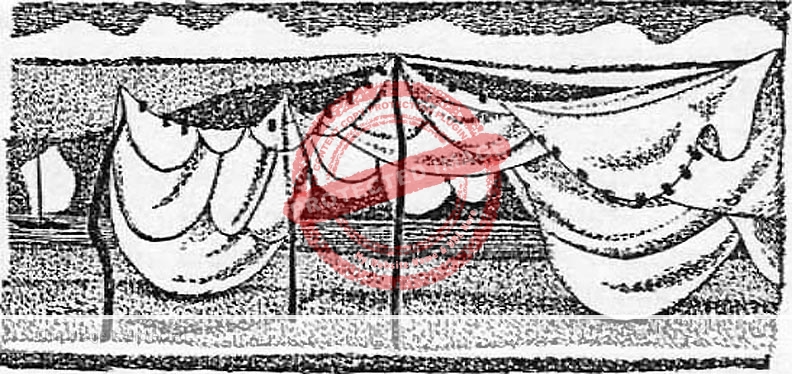

Everett Gee Jackson. ca 1923. Fisherman’s Shacks, Chapala. (from Burros and Paintbrushes: A Mexican Adventure, 1985)

When Jackson, newly engaged to Eileen, returned from El Paso, he discovered that Lowelito had decided to rent another house not in Chapala but in the smaller, more isolated, village of Ajijic.

Jackson is almost certainly correct in writing that they were the “first art students ever to live in Ajijic”, but there may be a hint of exaggeration in his claim that they were, “the only Americans living in Ajijic.”

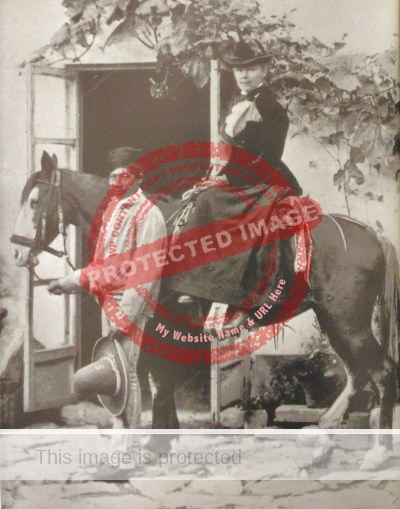

In July 1926, Jackson returned to the U.S. to marry Eileen and then brought his wife to Mexico for an unconventional honeymoon, sharing a house in Chapala with Lowelito and another boyhood friend. The house the group rented, for the princely sum of $35 a month, was none other than El Manglar, the then semi-abandoned former home of Lorenzo Elizaga, a brother-in-law (via their respective wives) of President Porfirio Díaz, who had stayed in the house on several occasions in the early 1900s.

Among Jackson’s Chapala-related works from this time (and exhibited in Dallas and San Angelo, Texas, in 1927) are “The Lake Village,” which won first prize at the Texas State Fair in Dallas (October 1926) and “Straw Shacks in Chapala.” These two paintings were glowingly described by art critic Dorcas Davis: “Here the art lover finds a blending of beauty and almost startling truth. These two pictures catch the glaring yet softening influence of the light of the sun upon the sand and adobe that is typically Mexican. The very blending of pastels and light and shadow create the illusion of southern atmosphere.”

Also exhibited in 1927 were “The Mariache” (aka “The Mexican Orchestra”), painted in 1923, and several portraits including “Eileen”, “Aztec Boy” and “Ajijic Girl.” In addition, Jackson showed a painting of “The Church of Muscala” (sic), The village of Mezcala had clearly made an indelible impression on Jackson (as it has on many later visitors), with one reporter writing: “The painter has told many interesting stories of Muscala where these isolated and primitive Indians, who have never heard of socialism and Utopia, have formed a government where everything is owned in common.”

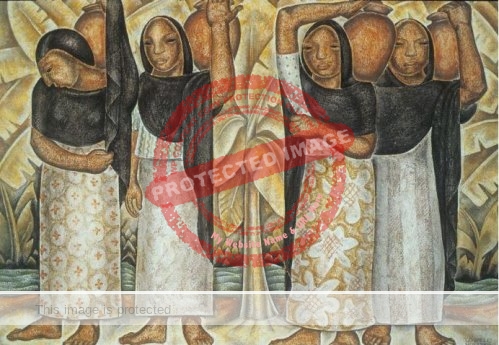

After numerous adventures in Chapala, in November 1926 the group moved to Mexico City, where the connection to Anita Brenner ensured they were welcomed by an elite circle of young artists and intellectuals that included Jean Charlot (1898–1979). They were also visited by the great muralist José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949). Early the following year, at Brenner’s insistence, Jackson and his wife visited the Zapotec Indian area of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec before returning home to San Diego.

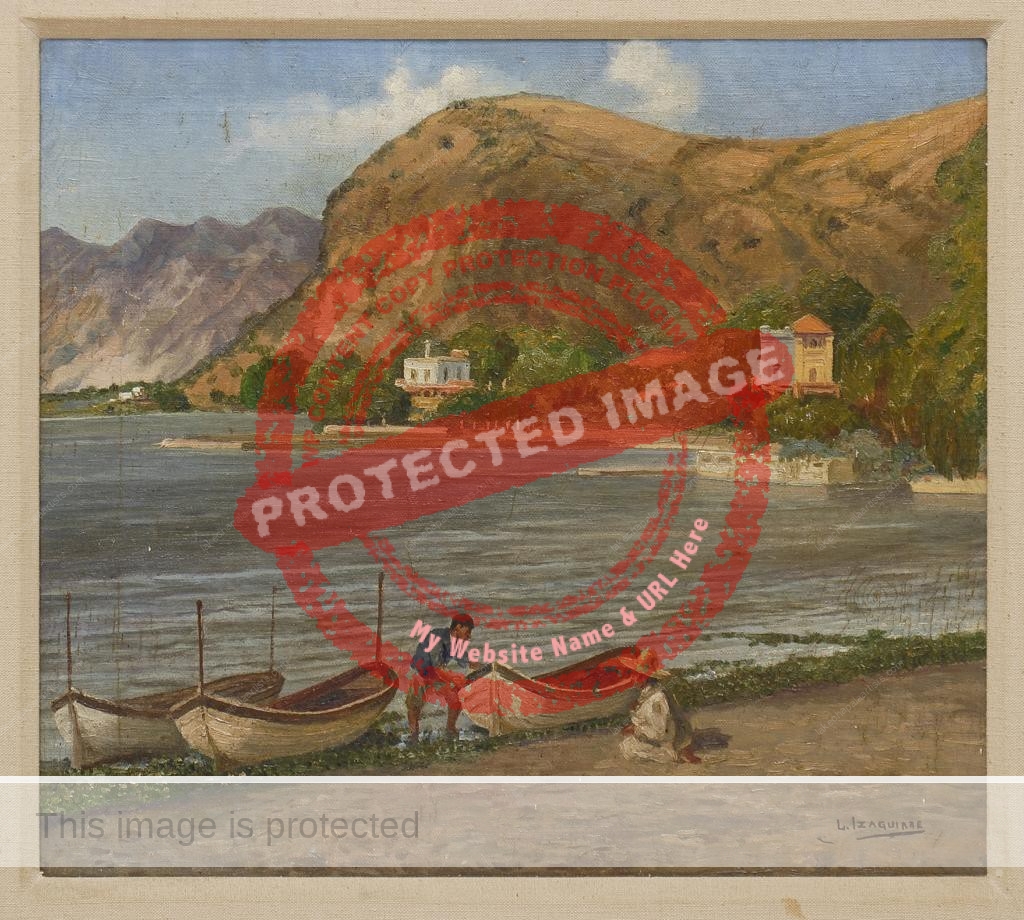

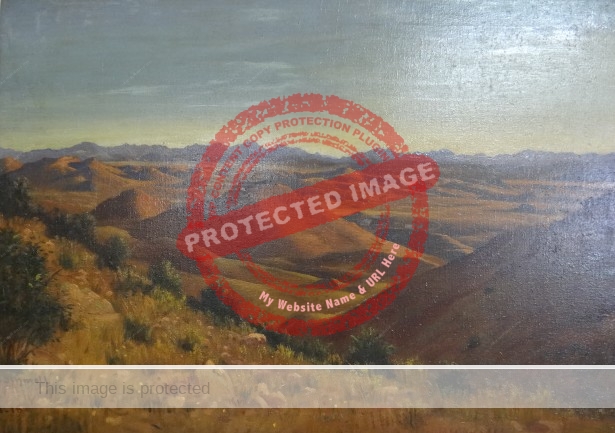

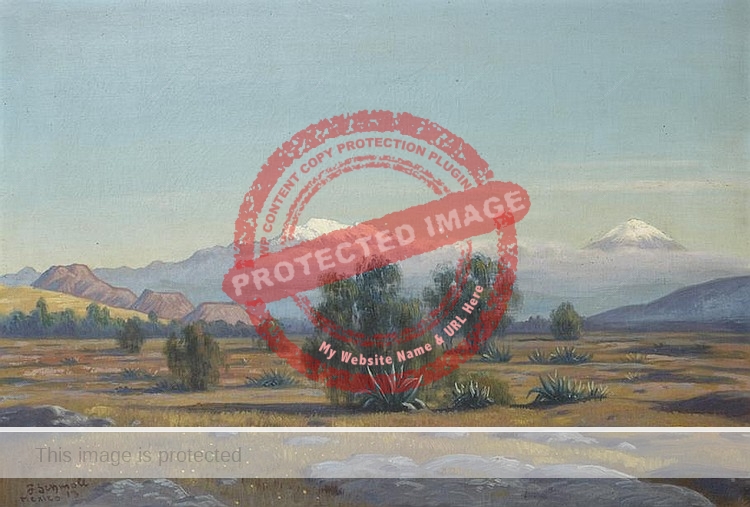

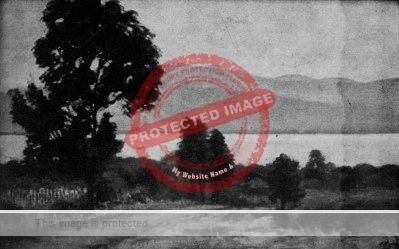

Everett Gee Jackson. 1926. Lake Chapala. (Hirshl & Adler Galleries, New York)

Even before their return, fifty of Jackson’s Mexican paintings had been exhibited at the “The Little Gallery” in San Diego. The exhibit was warmly received by critics and art lovers and further showings of his “ultra-modern canvasses” were planned for venues in Dallas and New York. Among the paintings that attracted most attention in The San Diego exhibition were “The Lake Village,” (Chapala), which had won first prize at the Texas State Fair in Dallas in October 1926, and “Straw Shacks in Chapala”.

There is no question that Jackson’s subsequent artistic trajectory owed much to his time in Chapala at the start of his career. His encounter with Mexican art — from pre-Columbian figurines to modern murals — transformed him from an impressionist to a post-impressionist painter. He was one of the first American artists to be so heavily influenced by Mexican modernism, with its stylized forms, blocks of color and hints of ancient motifs. Jackson’s work remained realist rather than abstract.

Jackson’s work was widely exhibited and won numerous awards. His major exhibitions included Art Institute of Chicago (1927); Corcoran Gallery (1928); Whitney Museum of American Art; School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1928; 1946); Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (1929-30); San Francisco Art Association; San Diego Fine Arts Society; and the Laguna Beach Art Association (1934). Retrospectives of his work included a 1979 show at the Museo del Carmen in Mexico City, jointly organized by INBA (Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes and INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia); and an exhibit at San Diego Modern in 2007-2008.

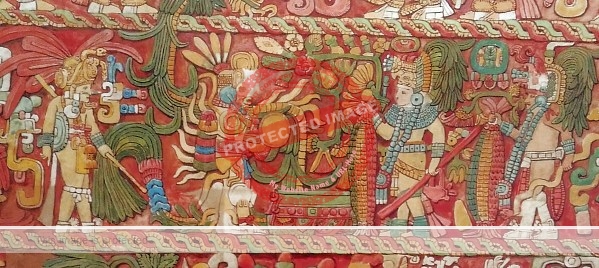

Jackson’s wonderful illustrations enliven several books, including Max Miller’s Mexico Around Me (1937); The Wonderful Adventures of Paul Bunyon (1945); The book of the people = Popol vuh : the national book of the ancient Quiché Maya (1954); the Heritage Press edition of Prescott’s History of the Conquest of Peru (1957); Ramona and other novels by Helen Hunt Jackson (1959); and American Indian Legends (1968) edited by Allan Macfarlan.

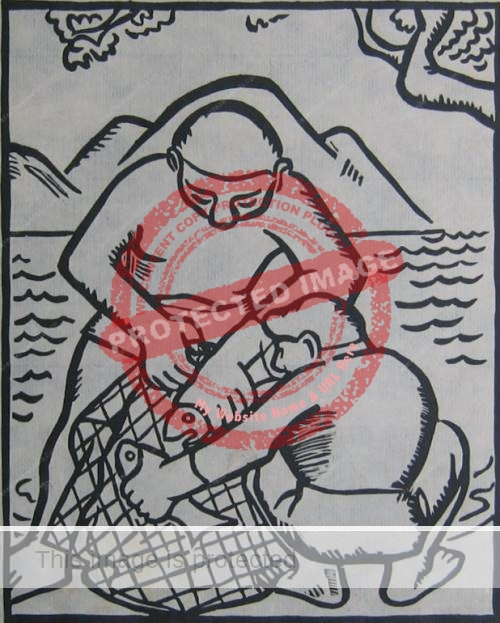

Everett Gee Jackson, Drying Nets, ca 1924., pen and ink. (from Burros and Paintbrushes: A Mexican Adventure, 1985)

In addition to his two volumes of memoirs, Jackson also wrote and illustrated Goat tails and doodlebugs: a journey toward art (1993).

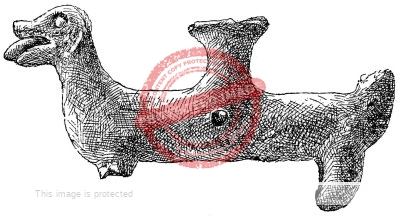

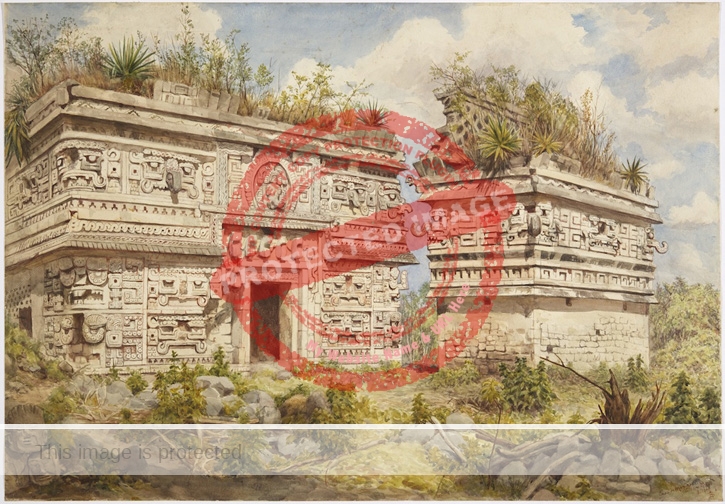

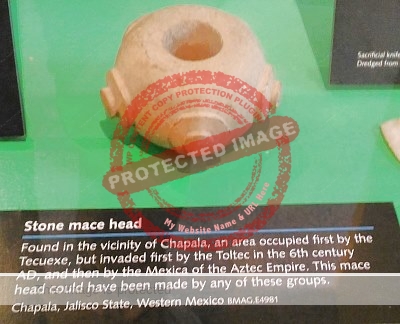

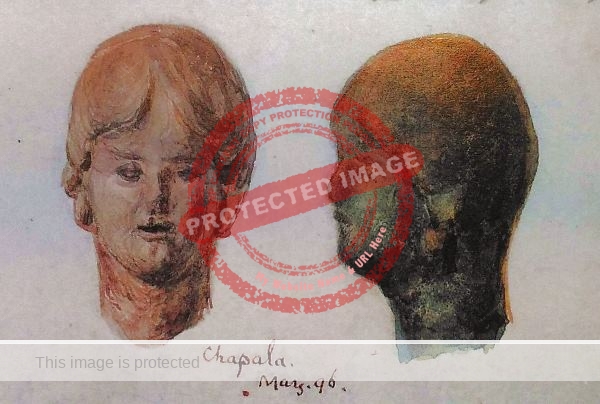

Jackson’s time in Mexico led to a lifelong interest in pre-Columbian art, as evidenced by his short paper, “The Pre-Columbian Figurines from Western Mexico”, published in 1941, and his book, Four Trips to Antiquity: Adventures of an Artist in Maya Ruined Cities (1991). In his 1941 paper, which included images of two figurines found at Lake Chapala, Jackson considered the varying degree of abstraction or expressionism in different figurines.

In 1950, Jackson (without Eileen) and Lowelito returned to Chapala for the first time since they had lived there. During their trip, the purpose of which was to find materials for teaching the history of Middle American art, they met up with various old friends, among them Isidoro Pulido:

“Isidoro had become a maker of candy and a dealer in pre-Columbian art in the patio of his house on Los Niños Héroes Street. I did not teach him to make candy, but when he was just a boy I had shown him how he could reproduce those figurines he and Eileen used to dig up back of Chapala. Now he not only made them well, but he would also take them out into the fields and gullies, bury them, and then dig them up in the company of American tourists, who were beginning to come to Chapala in increasing numbers. Isidoro did not feel guilty when the tourists bought his works; he believed his creations were just as good as the pre-Columbian ones.”

Jackson also revisited Chapala, this time accompanied by Eileen and their younger grandson, in summer 1968, when they rented the charming old Witter Bynner house, then owned by Peter Hurd, in the center of Chapala:

“We always called the house “the Witter Bynner house” because that American poet made it so beautiful and so full of surprises while he was living in it.”

Everett Gee Jackson, author, pioneering artist, illustrator and much more besides, died in San Diego on 4 March 1995.

[Jackson’s wife Eileen Jackson, who had studied journalism, was published in The London Studio and became the society columnist for the San Diego Union and San Diego Tribune for more than fifty years.]

Acknowledgment

- My thanks to Texas art historian James Baker for his interest in this project and for sharing his research about Everett Gee Jackson.

Sources

- Anon. 1927. “Talented Artist Of Mexia To Have Dallas Exhibition”, Corsicana Daily Sun, 29 Jan 1927, p 13.

- Archives of American Art. 1964. Oral history interview (by Betty Hoag) with Everett Gee Jackson, 1964 July 31. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- D. Scott Atkinson. 2007. Everett Gee Jackson: San Diego Modern, 1920-1955. San Diego Museum of Art.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1941. “The Pre-Columbian Ceramic Figurines from Western Mexico”, in Parnassus, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Jan., 1941), pp. 17-20.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1985. Burros and Paintbrushes, A Mexican Adventure. Texas A&M University Press.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1987. It’s a Long Road to Comondú. Texas A&M University Press.

- Jerry Williamson. 2000. Eileen: The Story Of Eileen Jackson As Told By Her Daughter. San Diego Historical Society.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

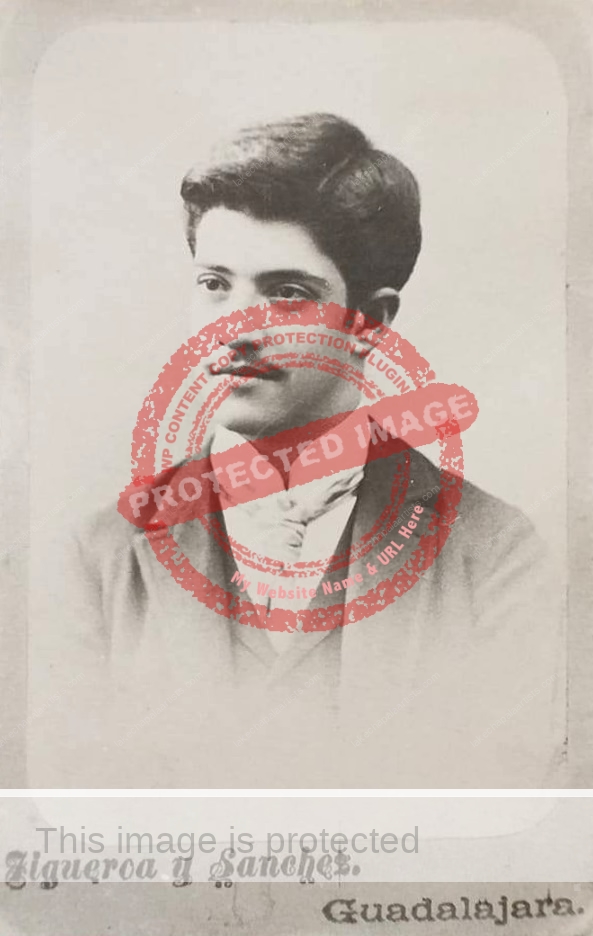

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.