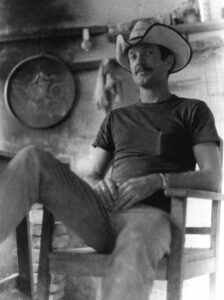

Following an initial conversation some months ago about his time in Jocotepec, Tom Brudenell, who lived in Jocotepec from 1967 to 1970, reviewed his notes and journals from that time, together with later drawings, paintings, and murals, to consider how Mexico has influenced his later work.

The following extracts offer fascinating insights into the mind, thoughts and personality of this hugely talented artist:

In 1967… I drove to Mexico but could not escape myself… I left for Mexico at a troubled time in my life to reflect and immerse myself in an “inward” journey. I came alone and stayed solitary for most of that time. Some friends and visitors followed. Except for brief periods of intense activity and exchange of ideas, solitude, to the point of losing touch with what one calls “reality”, describes my period in Mexico, before Susie came to live with me.

Before Jocotepec, I had already spent time with Len Foote in Tlaquepaque and on digs and explorations around La Barca. I recall staying at a rancho/ejido where my job was to screen for pot shards, and explore some caves for pre-Columbian artifacts, for Len’s work with the Universidad Autónoma in Guadalajara. There, too, I was alone most of the time. However, living in the bodega next to my two-room quarters were the caretakers, an ancient (to me) couple, Don Ambrosio and Doña Angelita.

If I were to describe the most powerful influences Jalisco (and to some extent Michoacán) had on me as a person, and as an artist, I would certainly include the quiet strength and dignity of this ancient, diminutive couple, Don Ambrosio and Doña Angelita. It was said that they had fought together with Emilio Zapata in Michoacán.

“From them I learned to make pulque from the maguey and speak a little campesino Mexican with a Jalisco accent. At night, sleeping on the roof of my house with the stars overhead and the coyotes singing in the distance, or yapping as Golondrino, Don Ambrosio’s big dog, kept them away from the bodega.

Earth, Cosmos and this simple unadulterated couple were united in a timeless flow of life. This was the same wordless message that came to me when living [earlier] among the Navajos, where I also lived alone.”

[Another] powerful influence on me as a person and artist was the light. The natural light of the Mexican sun at the latitude of Jocotepec. The sun’s yellow light warms the ambiente [ambiance] of one’s surroundings as well as Father El Sol providing secure feelings of heat.

Color-vibrations are seen everywhere in Mexican and Indian designs. The natural flora exude purples in sharp contrast with lime greens, reds flashing next to blues. Intense sunlight can dominate flat surfaces and color-vibrations, strong forms and colors shout back so that they find a happy balance. In the north, the light is bluer and the palette changes to take advantage of the subtle depth of the hue, the richness of color saturation. On the northwest coast I became enthralled with the silver of a flat sea and the copper and bronze of the forest floor. But this did not cancel out the forms, bold use of color and color-vibration learned in Jocotepec.

Another big influence of Jocotepec [was] once again, the dignity and strength of the village people – my neighbors – the weaver next door who spoke in a Veracruz dialect so fast that I struggled to keep up. He invited me for ponche one hot day. He cut off the tip of a pepper from his hottest plant and we dipped it a few times in our drinks. As the alcohol and picante took its effect we talked more personally, as best as I could manage. His loom and yarns and whole business surrounded us outside underneath his sombra [shade]. I asked him how he liked the organic garbage I’d give him over the wall for his pigs. He told me that he fed his pigs only grains. I asked him what he did with my garbage. He said that he gave it to Chuy, the garbage man, who also came to my house. We laughed heartily at this ridiculous miscommunication.

Chuy, the garbage man, another inspiration and influence. He did not wear gloves. He’d pick up the swept-up piles of street debris with his bare hands. When I asked him about the dangers of scorpions, he showed me his leathery hands and stabbed at them, saying “No pica; no pica!”

[Similarly], a leather maker in a tiny shop near the mercado in Guadalajara who replaced my broken boot string – from a whole steer hide – and to smooth off the edges of the cut-out string, he ran it through his extra-strong and long thumb and finger nails. Like Chuy, he was his work. His personhood and his work were one.

This strength and integration of the ordinary people with their environment and life was an honor to experience. Even today, in Canada, I buy early strawberries only [if they come] from Watsonville, California, where my Jocotepec neighbor convenience shop’s proprietor worked several months out of the year.

Finally, and sadly, but not surprisingly, I was again reminded of racism that is part of all cultures, when I enjoyed some late evenings in Jocotepec’s plaza with Indian fishermen from the nearby villages on the lake. When I wanted to continue our conversation, they informed me that it was midnight and they were not allowed in town after that hour…

Another influence of Mexico generally on me as a person and as an artist was the grandness and fearlessness of artisans tackling larger than life projects with minimal equipment and on-the-spot creative solutions to the problems placed in front of them, the grand scale and ease with large drawings that I witnessed in Orozco’s murals in Guadalajara, I also found in the Mexican agricultural workers’ children that worked on my people’s murals in the Yakima Valley of Washington State. Watching construction of a high-rise in Guadalajara, I saw concrete mixed in a hole on site rather than bringing in a cement truck; in Jocotepec, I was always amazed at the elaborate fireworks constructions and the emptying of the jail to add to the “volunteer” workers.

In Mexico’s villages and city centers, I was always comforted by the presence of art, mostly public art and Indigenous people’s art, worn or carried. Most of all, Mexico always provided me with incongruous experiences, like Yaqui soldiers guarding the train from Nogales to Guadalajara [while] reading comic books and shooting at jackrabbits from the windowless chandeliered car.

Then picture a soldier in battle gear and camouflaged helmet on maneuvers in Parque Azul [Guadalajara], drinking a refresco and reading a comic.

At the same time, there were nightmarish “unreal” experiences at times in and around the Lake area. But this is to be expected, where life is not sanitized, standardized, ordered and regulated, and where the culture and people are more directly touched by the fundamental beauty and tenor that underlies the thin layer of gentrification and order we rely upon for our contentedness and security. Unfortunately, that security can lull us to sleep so that we miss the middle to the last part of the show. Some might want to; I have learned, partly due to my lesson in Chula Vista (1969) that one cannot change the world or another person unless you first change yourself. Then you have changed the world. As Krishnamurti has said, “You are the world and the world is you.”

I go further now as I combine Krishnamurti with quantum mechanics and astrophysics and consciousness: “You are the Universe, and the Universe is you.”

I no longer see “hypnotic” narrowing of focus to be the same as “quieting the brain” and observing the Present.

Copyright Tom Brudenell, 1968, 1969, 2015

My sincere thanks to Tom Brudenell for allowing the publication of these photographs and extracts from his private journals.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

This man has always been my idol, from early childhood I admired him for his minds eye of the world. Uncle Tommy gave me my first fabulous art supplies, chalks in every color, the christmas gift he gave me in 1971 as a 7year old girl validated me somehow. Sparked my creativity and the way I saw nature. I’m very proud of him for always following his dreams, staying true to himself and sharing his beautiful art. Uncle Tommy continues to be inspiring. Much Love, MOE