José Edmundo “Pepe” Sánchez Rojas (c. 1888-1933), the son of Juan Sánchez and Ceferina Rojas, was born and raised in Chapala. His paternal grandparents were the exceptionally long-lived J. Guadalupe Sánchez (1806-1896) and María Dolores Pantoja (c 1799-1905), who died in Chapala on 22 May 1905, aged 106, according to her death registration. Jose Edmundo’s immediate family included individuals who served as mayor of Chapala (on more than one occasion) and as administrator of the local postal service, a position of some prestige at the start of the twentieth century.

We know nothing about José Edmundo Sánchez’s early life, education, or how he gained proficiency as a photographer. But he is the first professional photographer born in Chapala, and he appears never to have taken photographs anywhere else. Over a relatively short but productive career, he produced hundreds of real photo postcards, at a time when the town’s tourism attractions were gaining international attention.

He did have sidelines. In 1920, Sánchez and a friend—the renowned architect Guillermo de Alba—opened a bar named the Pavilion Monterrey in Chapala where food and drinks were served in an open-air pavilion facing the lake. The bar was just back from the beach, mid-way between the Arzapalo Hotel and the Casa Braniff (now the Cazadores restaurant). De Alba helped run the bar until 1926 when he moved to Mexico City.

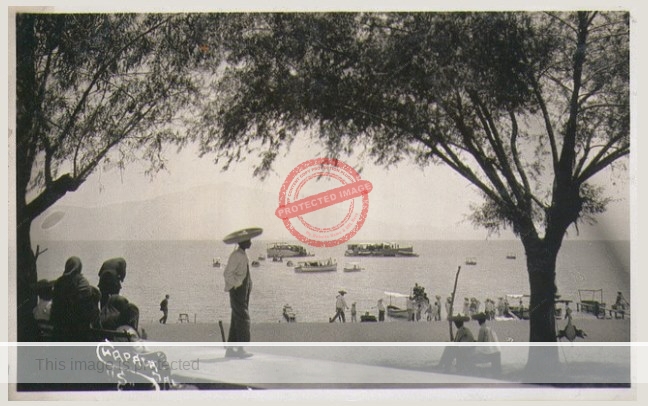

José Edmundo Sánchez. Lakefront, Chapala, c. 1920.

By happy coincidence, both Sánchez and de Alba were keen and skilled photographers. Their discerning eye and considerable talent resulted in numerous sensitive and artistic images of Chapala, among the finest images of the town ever taken. While de Alba does not appear to have ever commercialized his photographic work, Sánchez certainly did. He took a large number of views of Chapala and was keen to sell them, going so far as to emblazon “tarjetas postales” in paint across the wall of his lakefront bar. Sanchez also sold photography-related items, and developed and printed films for others. In addition, he showed movies on Saturday afternoons, years before any formal cinema was established in the area, and at a time when the town only had one power plant.

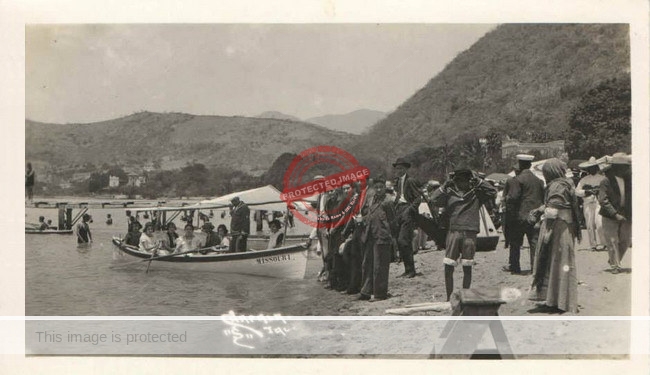

José Edmundo Sánchez. Beach and boat trips, Chapala, c. 1920.

Sánchez married María Guadalupe Nuño in about 1920; the couple made their home at Calle San Miguel (now Lopez Cotilla) #18. She helped run the bar, perhaps to make sure her husband and his pals did not drink all the profits.

In addition to raising several children, María Guadalupe accidentally hit upon the recipe to ensure the family’s future financial security. By the time D. H. Lawrence and the American poet Witter Bynner arrived in Chapala in 1923, she had perfected a chaser for tequila, made of freshly-squeezed orange juice, spiced up with salt and powdered red chile peppers. Vegetable coloring was later added to heighten the chaser’s blood-red color. The chaser, christened sangrita (“little blood”), quickly became the preferred accompaniment for tequila drinking sessions, and its fame spread nationwide.

Tragically, José Edmundo Sanchez’s photographic career came to an abrupt end when he died of gunshot injuries at his home in Chapala on 15 July 1933; he was only 45 years old.

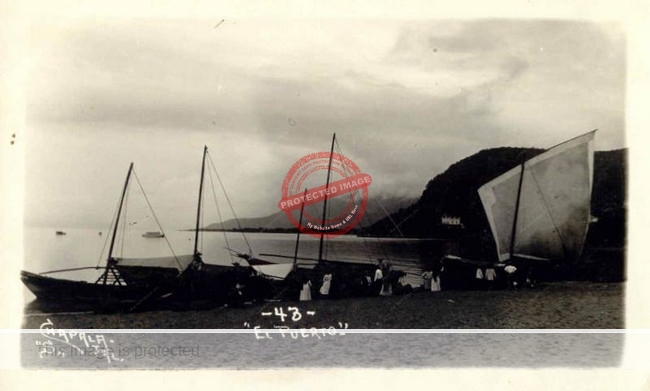

José Edmundo Sánchez. El puerto, Chapala, c. 1920.

[Aside: At about the time Sánchez died, a specially commissioned plinth was placed alongside the bar for a unique twenty-year-old sculpture of a lioness, created by master stonemason Faustino Gil, using volcanic ash collected from the streets of Chapala after the major eruption of Colima Volcano in January 1913. Later photos show only an empty plinth, and the plinth itself was destroyed when Avenida Francisco I. Madero was created in about 1950. Does the sculpture still exist somewhere in Chapala? Is the lioness prowling the streets at night?]

Sánchez’s photographs

American poet Witter Bynner, who knew a thing or two about art, described Pepe Sanchez as “an expert photographer, whose prints of Chapala are a selective and artistic record of its aspects in those years.” Another American who lived in Chapala in the 1920s, the artist Everett Gee Jackson, also knew Sr. and Sra. Sánchez at that time and was delighted to be instantly recognized by Widow Sánchez when he and his friend Lowelito paid a return visit to the town in 1950 and visited her bar for a drink: “I was surprised at the reception she gave me. She greeted me as an old friend, although I had known her but slightly, as the wife of Mr. Sánchez, the village photographer.”

José Edmundo Sánchez. Chapala, c. 1910. Postcard, courtesy of Ing. Mario González García.

Among the early photos taken by Sánchez is one of the Gran Hotel Victor Huber, which was located across the street from the Hotel Arzapalo. The hotel was only in operation under this name for a short time, from 1908-1909, before it was renamed Hotel Francés. It is likely, though, that (as is the case for several other old buildings in Chapala) the sign on the upper story remained in place for some years after the hotel had been renamed. All known Sánchez photographs were taken in, or very near, Chapala.

Most of Sánchez’s photographs, including those reproduced and sold as picture postcards, almost certainly date from the 1920s and start of the 1930s. From an historical viewpoint, noteworthy images include panoramic views from Cerro San Miguel, showing how modern villas sprawled along the lakeshore west of town, and several superb images taken under trying circumstances in October 1926 when the lake level rose so high that it flooded all the low-lying areas of the town, including the Chapala Railroad Station.

José Edmundo Sánchez. Casa Capetillo, Chapala, 1926.

Sánchez used several different photographic papers for his postcards, and added several distinct signatures, ranging from his initials J.E.S. to a flowery, elaborate cursive script spelling “Sánchez”, and, most commonly, a single “S„ alongside a distinctive initial C (with an elongated tail) for “Chapala.” Only a very small number of his cards include a date. The wide range of cards he produced begs for further research to try to establish if the various signatures were used sequentially or concurrently.

At least one Sánchez photograph—of shoreline villas as seen from the lake—was reprinted by Mexico City photographer Hugo Brehme in the late 1920s. It is unclear whether or not Brehme purchased the rights, though the reverse side of the reprint carries the typical Brehme handstamp: “Propriedad Asegurada Hugo Brehme.”

Of the postally used examples of Sánchez postcards I’ve seen, the prize for the most poignant message goes to a young girl named Hilda, who wrote on a card showing sailboats in Chapala, which she then mailed to her father in Tampico: “Dear Daddy, How are you? I am waiting for a letter from you or I won’t send another card. Love from Hilda.”

Photographs taken by Sánchez have rarely appeared in print media, but are frequently reproduced—almost invariably uncredited—in social media posts relating to Lake Chapala. The surviving work of pioneering local photographer José Edmundo Sánchez is an important part of the cultural heritage of Mexico’s first international tourist destination, and deserves our recognition and respect.

If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants, translated into Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes, has more about Sánchez and the early history of tourism in Chapala, while Lake Chapala: A Postcard History—which gives a broader sweep of the area’s development—includes several additional Sánchez photographs.

Note. Several descendants of José Edmundo Sánchez were apparently also keen photographers, though attempts to locate examples of their work have so far been largely unsuccessful.

Sources

- Witter Bynner. 1951. Journey with Genius. New York: The John Day Company.

- Aurelio Cortés Diáz. 1988. Semblanzas tapatías, 1925-1945. Guadalajara: Gobierno de Jalisco.

- Chente García. 2002. “Chapala.” Chapter in Jaime Alvarez del Castillo (coordinator). 2002. Arquitecto Guillermo de Alba. Guadalajara: Editorial Agata/Fotoglobo.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1987. It’s a long road to Comondú: Mexican adventures since 1928.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

A wonderful read today.

Hola Tony. Wonderful story about the “sangrita” . i heard that when la señora Guadalupe help her husband in the Monterrey Cantina she served some botana for free with the first tequila that they order

That consist of a bowl with Orange, Jícama and cucumber with lemon Salt and crush Chile. “Pico de Gallo” it is call. So on one ocasión a regular customer when the fruit was finish got the bowl and drink the remanents of the liquid of the fruits mixed with the lemon and chile whiile ziping his “caballito” de tequila and found that both complement very good.

So Doña Guadalupe notice that and she begin preparing the wonderful Sangrita now Viuda de Sánchez.

Salud!

Jorge, Thanks for this interesting and informative recollection. ¡Salud!

Thank You for the Article on Jose Edmundo Sánchez

Hi,

Thank you so much for your article about Jose Edmundo Sánchez. I’m his great-granddaughter. My grandfather, Ignacio Sánchez Ruíz, also knew how to make Sangrita. He passed away when I was six years old and never spoke about his father, so there’s a lot I don’t know about his life.

I’ve been researching my family’s history, and your article was truly meaningful to me. I live in Mexico and hope to visit Chapala sometime soon.

If you have any more information or stories you’d be willing to share, please feel free to contact me.

Warm regards,

Pranam Diana Sánchez

Hi Pranam, Thanks for your kind and informative comments. If I ever find out more about your great grandfather, I’ll be sure to let you know. Equally, if you come across any additional material in your research which you think would be interesting to me, do please get in touch! Warm regards, Tony Burton.

Hi Tony, thank you for the acknowledgement of the Sanchez legacy in your article. A couple of dates for the grandparents of Jose Edmundo Sanchez Rojas.

Per their marriage records of 1828 Doña Maria Dolores Pantoja Ponce was 14 years old at the time of her marriage, she married Jose Guadalupe Sanchez Pantoja 16 years old and an orphan (they shared a grandfather 3 and 4 generations respectively). Warm regards Carmen Mosqueda

Hi Carmen, Thanks for these details. I’ll get back to you if I have any related queries. Warm regards, Tony.