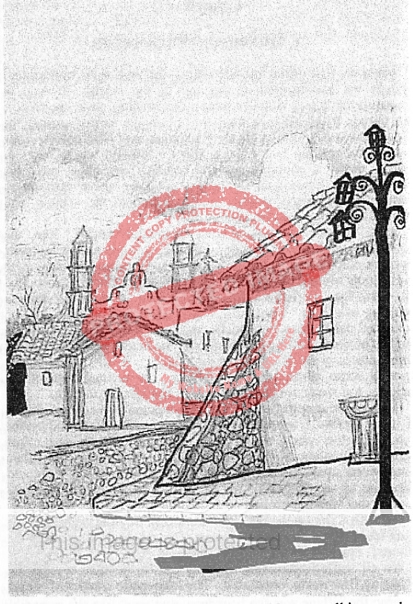

Gail Michel, as she was then known, arrived in Ajijic in 1961. Her talents as a businesswoman and dress designer, enabled her to start a store, El Ángel, close to the Posada Ajijic, that became so successful it was featured in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue Paris. Alongside her boutique, Gail continued to develop her own art and was a regular exhibitor in local group shows. Seventeen years and four children later, she moved back to the U.S.

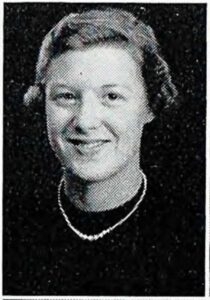

Born Julia Gail Hayes on 3 March 1935 in the small South Dakota town of Wasta, her university education at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, was interrupted by falling in love with a fellow student, Frank Clifford Michel, a psychology major. The young couple were married in Pullman on 12 December 1955 and had a son, David, but the relationship did not last. Gail, a competitive swimmer, gave swimming lessons to help finance university, completed her degree, obtained a divorce and, in 1961, after receiving a letter from a Colorado friend about the beauties of Ajijic, traveled to Mexico with David to start a new life.

Gail Hayes. 1955. (University Yearbook photo)

In Ajijic, she quickly found employment at Los Telares, Helen Kirtland’s handlooms business which had begun operations in the late 1940s. She also soon made many very good friends and decided to stay in the village, starting a serious, long-term relationship with a local contractor, Marcos Guzman, with whom she had four children.

During her time in Mexico, Gail was usually known as Gail Michel or Gail Michael (sometimes Michaels) before she opted for Gail Michel de Guzmán.

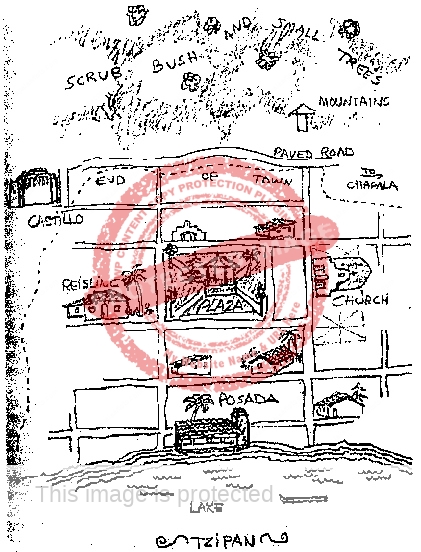

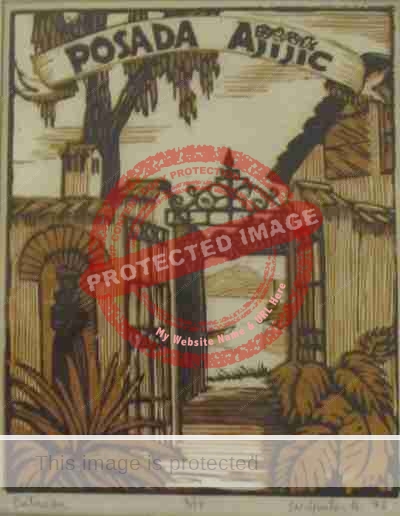

Gail credits Jane and Sherm Harris, the then managers of the Posada Ajijic, with persuading her to branch out on her own in 1964 and open a store selling her embroidered, hand-loomed dresses, original jewelry, paintings, and select Mexican handicrafts. The Harrises even provided the fashion boutique’s first venue: a room in the Posada. Its name, El Ángel, was in honor of her oldest daughter, Angelina. (The title of Al Young‘s 1975 novel Who is Angelina?, set partly in Ajijic, is apparently purely coincidental.)

Periodic fashion shows ensured that the El Ángel boutique quickly outgrew its temporary residence in the Posada. In April 1966, it moved a short distance away to the building (occupied later by La Flor de la Laguna) at the south-west corner of the Morelos/Independencia intersection. The boutique’s opening was attended by more than 250 people, an impressive turn-out given the size of Ajijic at that time. The store remained in that property for more than a decade before returning to its roots in the Posada Ajijic shortly before Gail returned north.

Veteran journalist Jack McDonald opened his informative and enthusiastic profile of Gail Michel in 1968 for the Guadalajara Reporter by describing her as “One of most creative, versatile gals in all Ajijic.”

“Her enchanting place offers passing tourists and permanent residents a variety of items such as art works, jewelry, rugs, bright hand-woven mantas, colonial furniture and antiques in stone, wood and metal.

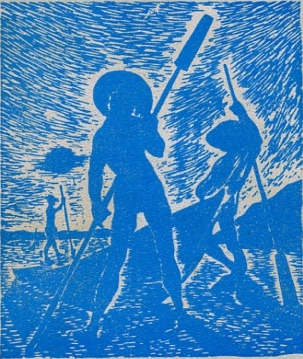

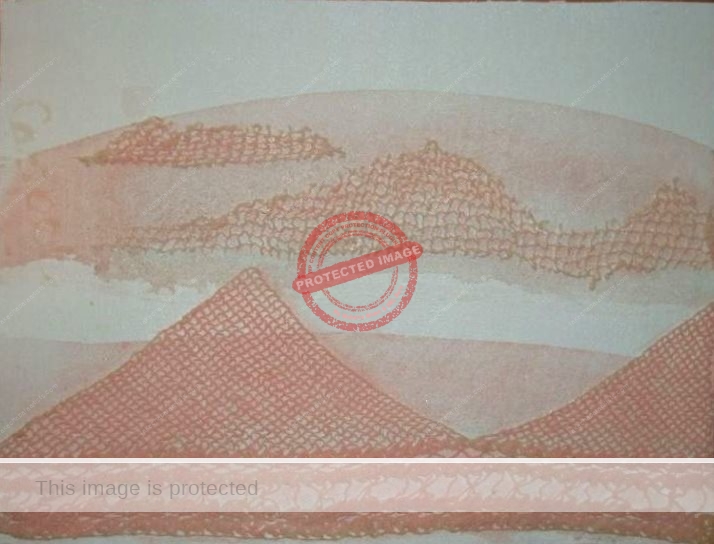

And dresses. As an outlet for her creative energies, which include her own paintings on rice paper with ink, she employs a dozen seamstresses and a staff of wood and stone carvers who cut anything from small figurines to water fountains.”

The El Ángel boutique, described later by long-time Ajijic resident Kate Karns as “the most beautiful of Ajijic’s three shops” at the time, was featured in Vogue Paris and recommended in the August 1970 issue of Harper’s Bazaar.

By December 1969, Gail, now described as “a well known expert on Mexican arts and crafts” was also managing the gift shop at the Villa Montecarlo in Chapala.

In 1974, Gail was one of only four “members of the Ajijic business community” invited to participate in a program for Guadalajara TV Channel 6 to celebrate the first anniversary of the state’s “Conozco Jalisco” (“Know Jalisco”) campaign. (The other invitees were Jan and Manuel Ursúa of the Tejabán Restaurant and Boutique, and Antonio Cardenas, the owner of La Canoa boutique.)

[Aside: Jan Ursúa, better known as Jan Dunlap, recently published her first novel, Dilemma, set in 1970s Ajijic.]

Everyone I’ve interviewed who knew Gail Michel de Guzmán in Ajijic has expressed their fond memories of her. Many have also shared favorite anecdotes. Eunice Huf, for example, recalled Gail as a young blonde girl with freckles who designed both jewelry and dresses with simple, elegant, lines. She chuckled as she told me how Gail had once dressed her up in a crocheted top that was so sexy it made even their fellow artist Abby Rubenstein jealous!

The late Tom Faloon openly expressed his admiration for Gail’s art, and then laughed as he remembered how on one occasion Gail, on learning that Marcos had a new girlfriend, had once deliberately driven her car into the girlfriend’s vehicle. The next day, a contrite Gail went to the police station to admit her wrong-doing but found, to her pleasant surprise, that the police had no interest whatsoever in this or any other “crime of passion”!

As an artist, Gail participated in numerous shows during her time in Ajijic. Perhaps the earliest was in 1962 at the 1st Annual Exhibition of Paintings and Sculptures on Ajijic Beach, organized by Laura Bateman’s Rincón del Arte gallery. Other artists from Ajijic in this juried show with prizes included Antonio Cárdenas, Mary Cardwell, Juan Gutiérrez, Dick Keltner, “Linares” (Ernesto Butterlin), Carlos López Ruíz, Betty Mans, John Minor, Eugenio Olmedo, Florentino Padilla, Alfredo Santos, Gustavo Sendis, Tink Strother, Digur Weber, Doug Weber, Rhoda Williamson, Sid Williamson, Javier Zaragoza and Paul Zars.

One of the earliest was the Posada Ajijic’s Easter exhibit in April 1966. Other artists on that occasion included Jack Rutherford; Carl Kerr; Sid Adler; Allyn Hunt; Franz Duyz; Margarite Tibo; Elva Dodge (wife of author David Dodge); Mr and Mrs Moriaty and Marigold Wandell.

In January 1968 Gail’s paintings were shown in an exhibition at El Palomar in Tlaquepaque, alongside works by Hector Navarro, Gustavo Aranguren, Coffeen Suhl, John K. Peterson, Don Shaw, Peter Huf, Rodolfo Lozano and Eunice Hunt. The following month, a group of Ajijic artists (Gail Michel and the members of “Grupo 68” – John K. Peterson, Eunice Hunt, Peter Huf, and Don Shaw) were reported to be exhibiting weekly, every Friday, at El Palomar, and also most Sunday afternoons at the Camino Real hotel in Guadalajara.

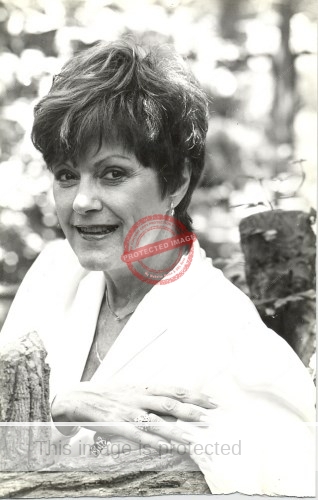

Gail Michaels. ca 1971. Photo by Beverly Johnson. (Reproduced by kind permission of Jill Maldonado.)

An appliqued wall-hanging by Gail was shown in a collective fine crafts show at Galeria Ajijic (Marcos Castellanos #15) in May 1968. Among the other artists at that show were Mary Rose, Hudson Rose, Peter Huf and Eunice Hunt (with their miniature toy-like landscapes complete with tiny figures and accompanying easels), Ben Crabbe, Joe Rowe, Beverly Hunt and Joe Vine.

Not surprisingly, Gail’s art was included in the large group show, Fiesta de Arte, in May 1971 at the private home of Mr and Mrs E. D. Windham (Calle 16 de Septiembre #33, Ajijic), along with paintings and sculptures by Daphne Aluta; Mario Aluta; Beth Avary; Charles Blodgett; Antonio Cárdenas; Alan Davoll; Alice de Boton; Robert de Boton; Tom Faloon; John Frost; Fernando García; Dorothy Goldner; Burt Hawley; Michael Heinichen; Peter Huf; Eunice (Hunt) Huf; Lona Isoard; John Maybra Kilpatrick; Bert Miller; Robert Neathery; John K. Peterson; Stuart Phillips; Hudson Rose; Mary Rose; Jesús Santana; Walt Shou; Frances Showalter; ‘Sloane’; Eleanor Smart; Robert Snodgrass; and Agustín Velarde.

In March 1975, three Ajijic painters – Gail Michel, Rocky Karns and Synnove (Shaffer) Pettersen – held a group show at the Villa Montecarlo in Chapala.

These three artists joined with Tom Faloon, Hubert Harmon, John K. Peterson, Adolfo Riestra, Sidney Schwartzman, to form a new group known as Clique Ajijic, a group of eight artists who formed a loosely-organized collective for three or four years in the mid-1970s. The group’s exhibitions included two in Ajijic – at the Galería del Lago (Colón #6, Ajijic) in August and at the Hotel Camino Real in September – as well as shows at Galeria OM in Guadalajara (October 1975); Club Santiago in Manzanillo (October 1975), the Akari Gallery in Cuernavaca (February 1976) and at the American Society of Jalisco in Guadalajara (also February 1976).

Gail’s first solo show of artwork was at Ajijic’s Galeria del Lago in April 1975. In February of the following year, the same gallery hosted an invitational group show – the so-called “Nude Show” – with works by Gail Michel, Guillermo Guzmán, John Frost, Jonathan Aparicio, Synnove (Shaffer) Pettersen, Dionicio Morales, John K. Peterson, Georg Rauch, Robert Neathery and others.

Gail’s work also formed part of a Jalisco state-sponsored show entitled “Arte-Artesania de la Ribera del Lago de Chapala” in October 1976 at the ex-Convento del Carmen. In addition to Gail, exhibitors on that occasion were Guillermo Gómez Vázquez; Conrado Contreras; Manuel Flores; John Frost; Dionicio Morales; Gustel Faust; Bert Miller; Antonio Cardenas; Antonio Lopez Vega; Georg Rauch; Gloria Marthai and Jim Marthai.

In December 1976, Gail also had work in a group show organized by Katie Goodridge Ingram for the Jalisco Department of Bellas Artes and Tourism, held at Plaza de la Hermandad (IMPI building) in Puerto Vallarta. The show ran from 4-21 December and also included works by Jean Caragonne; Conrado Contreras; Daniel de Simone; Gustel Foust; John Frost; Richard Frush; Hubert Harmon; Rocky Karns; Jim Marthai; Bob Neathery; David Olaf; John K. Peterson; Georg Rauch; and Sylvia Salmi.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and copies of Gail Michel de Guzmán’s original dress designs can still be found in some Ajijic stores.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to Gail Michel de Guzmán for her help compiling this profile of her time in Ajijic, and to Judy Eager, the late Tom Faloon, Katie Goodridge Ingram, Peter and Eunice Huf, and Enrique Velasquez for sharing with me their personal memories from that time.

Sources

- Guadalajara Reporter: 2 Dec 1964; 2 April 1966; 13 Jan 1968; 3 Feb 1968; 25 May 1968; 22 Jun 1968; 6 Dec 1969; 12 Sep 1970; 24 April 1971; 15 May 1971; 18 May 1974; 20 July 1974; 14 Dec 1974; 15 Mar 1975; 12 Apr 1975; 12 Apr 1975; 31 Jan 1976.

- El Informador (Guadalajara): 2 June 1962, 11; 25 Oct 1976.

- Kate Karns. 2010. “Old Ajijic”, Lake Chapala Review, Volume 12 #1, February 14, 2010.

- Jack McDonald. 1968. “Ajijic Woman Carved out Business for Herself …” (a profile of Gail Michel), Guadalajara Reporter 22 June 1968, p 15.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.