Carl Sophus Lumholtz (1851–1922), born in Lillehammer, Norway, was a scientist, traveler and anthropologist in the generalist Humboldtian tradition. After graduating from the Theology department of the University of Christianía in Oslo, Lumholtz went to Australia as a naturalist. While living with cannibalistic aborigines in northern Queensland, he became fascinated by the study of primitive peoples, and spent the rest of his life enthralled by the anthropology and ethnology of native tribes in many different parts of the world.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

His visits were supported by generous, wealthy patrons, as well as by the American Geographical Society and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Helped by letters of introduction from politicians in Washington, Lumholtz was able to obtain logistical support from President Porfirio Díaz, who Lumholtz considered to be “not only a great man on this continent, but one of the great men of our time.” Díaz helped organize a translation of Lumholtz’s work into Spanish. This was published, in 1904, only two years after the original English edition.

Lumholtz first entered Mexico with a team of some thirty scientists, with specializations ranging from geography to physics and from botany to mineralogy, and 100 horses. By the fourth trip, he had abandoned the team approach in favor of traveling alone, since this allowed him to explore some of the remotest parts of north and west Mexico, and live for extended periods of time with isolated Indian tribes. His respectful, patient attitude allowed him to gain the confidence of his hosts, and be permitted to take some of the earliest known photographs of them and their activities.

He was particularly impressed by the Indians’ practical skills:

“In all kinds of handicraft, for instance, in carving on stone, wood, and so forth, the ancient people of Mexico have no equal today for accuracy of execution and beauty of outline.” His sense of priorities is perhaps summed up best by his statement that he felt he had to protect the “Indians from the Mexicans, the Mexicans from the Americans”.

To his eternal regret, Lumholtz’s work in Mexico was interrupted by the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, and he felt forced to turn his attentions to other parts of the world, including India, Borneo and south-east Asia.

A prolific author, with dozens of works to his credit, Lumholtz died in 1922 while planning a research trip to New Guinea.

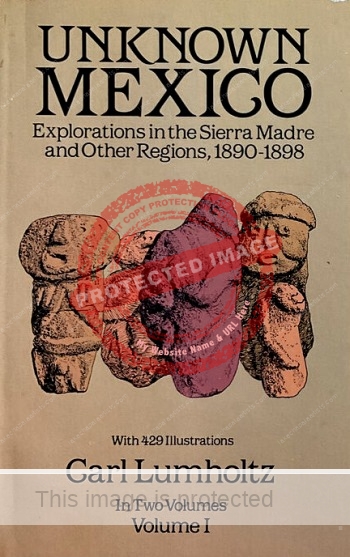

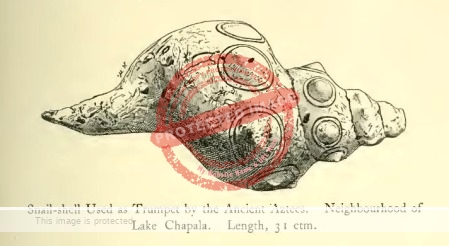

Unknown Mexico is an account of Lumholtz’s first four trips to Mexico, representing a total of five years in the country between 1890 and 1900. Even today, it remains a classic of anthropological literature. Illustrated with dozens of drawings and photographs, it provides a wealth of detail about the lifestyles, customs, native remedies, music and beliefs of some of the indigenous tribes.

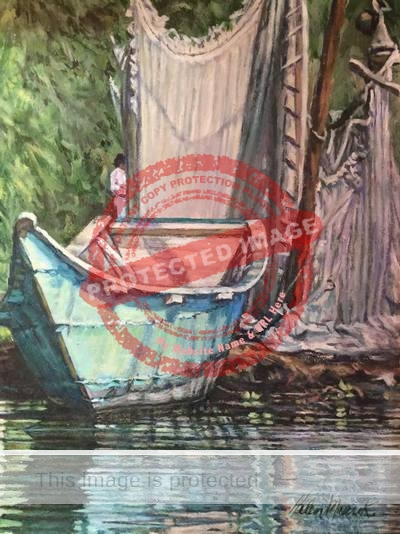

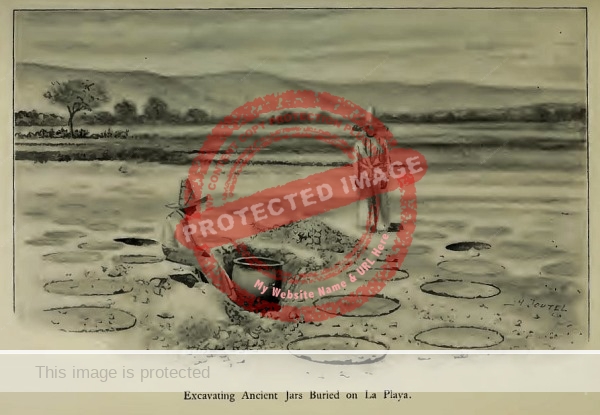

This illustration from Unknown Mexico shows the excavation of ancient jars near Atoyac (a short distance west of Lake Chapala):

Lumholtz. Unknown Mexico, vol 2, opposite page 318.

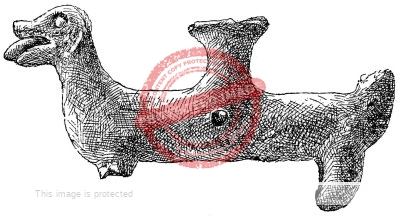

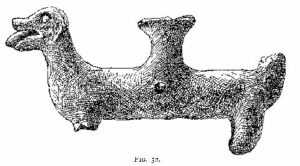

The book includes drawings of two ceremonial hatchets “used at sacred sites” and found in the “neighbourhood of Chapala”:

Lumholtz: Two ceremonial hatchets found near Chapala

I made also an excursion to the beautiful lake of Chapala, the largest sheet of fresh water in Mexico, fifty miles long and from fifteen to eighteen broad. Its name is Nahuatl, which should really be Chapalal, in onomatopoetic imitation of the sound of the waves playing on the beach. The stage runs to a small village of the same name, lying on the shore, where some pretty country houses have been built.

In this lake, especially at its western end, are found great quantities of ancient, roughly made, diminutive jars, and a number of other objects. Near the village of Axixic (Nahuatl, “Where water [atl] pours forth”) the people make a business of diving for them, threading them on strings, and selling them to visitors to the village of Chapala. I gathered several hundreds of them, and the supply seemed inexhaustible. No one knows when or why they were thrown into the lake. Most likely they were votive offerings to the deity of this water, to secure luck and health and other material benefits.

Lumholtz. Unknown Mexico. Illustration from Vol 2, page 357

Note: This is based on chapter 48 of my Lake Chapala Through the Ages: An Anthology of Travelers’ Tales.

Sources

- Carl Sophus Lumholtz. 1902. Unknown Mexico. 2 vols. 1973 reprint: New Mexico: Rio Grande Press.

- Luis Romo Cedano. “Carl Lumholtz y el México desconocido.” Ch. 13 of Ferrer Muñoz, Manuel (coordinator) La Imagen del México Decimonónico de los Visitantes Extranjeros: ¿Un Estado nación o un Mosaico Plurinacional? Mexico: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, Serie Doctrina Jurídica, Núm. 56.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.