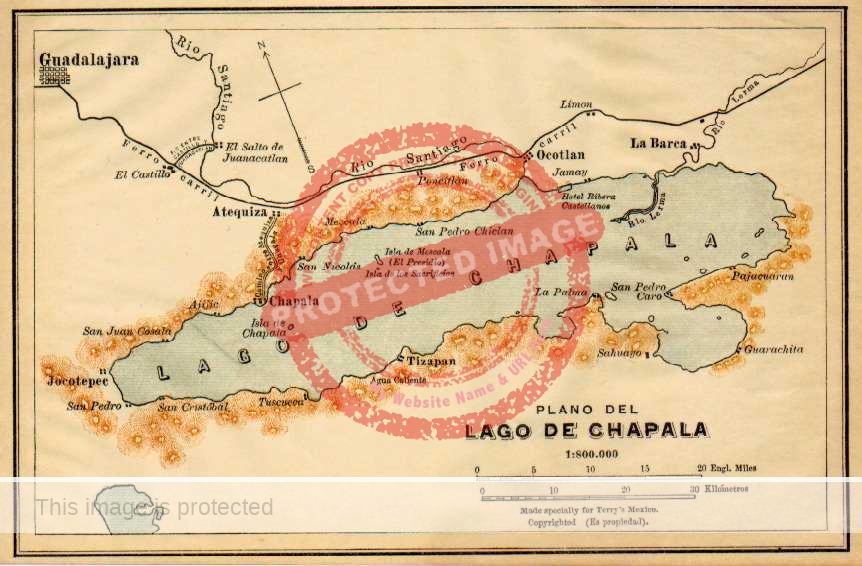

From the 1930s onward, several architects, most of them graduates of the Guadalajara engineering school, undertook modernist projects in Chapala. They included Pedro Castellanos Lambley, Juan Palomar y Arias and Ignacio Díaz Morales. But the one who became by far the most famous was Luis Barragán.

Who was Luis Barragán?

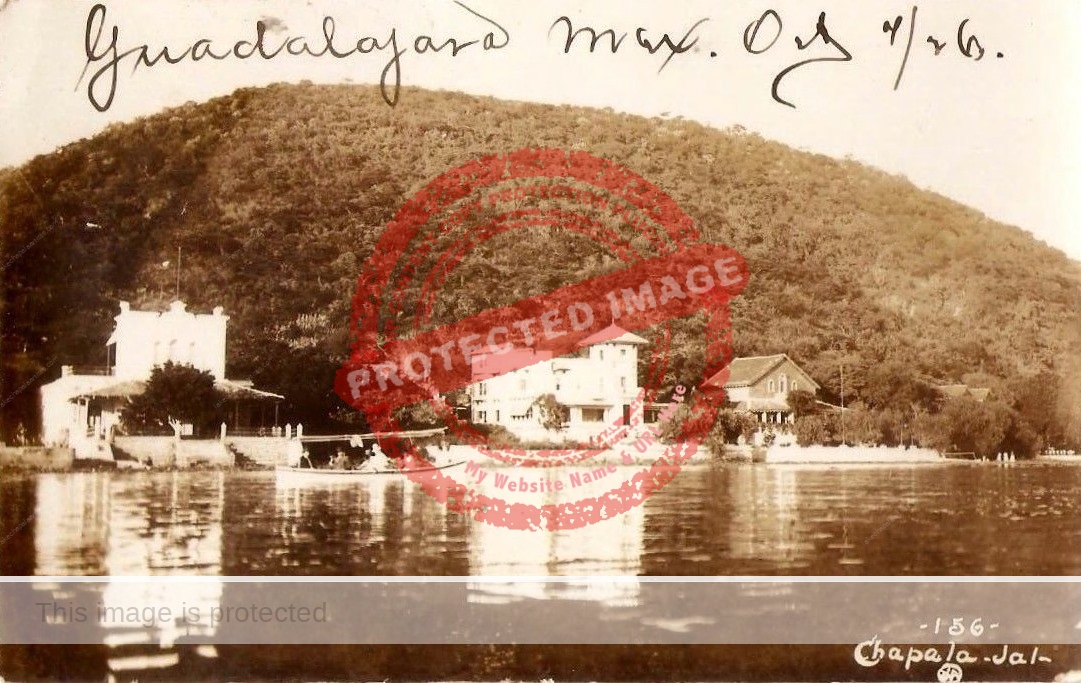

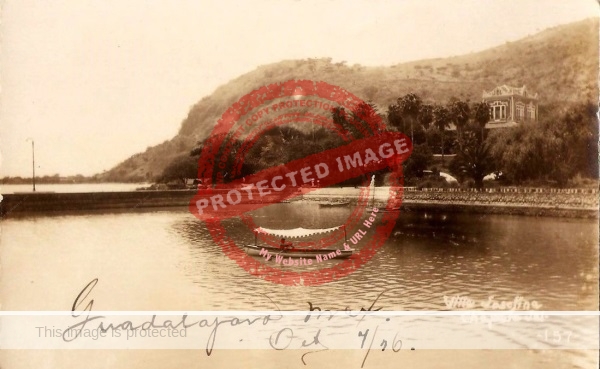

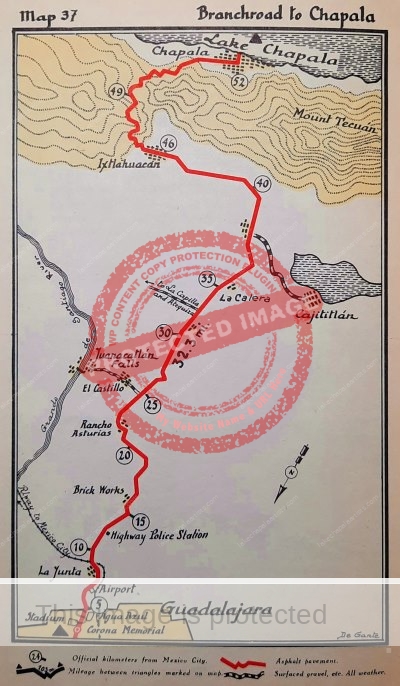

Often described as the most influential Mexican architect of the twentieth century, Luis Barragán Morfín (1902–1988) was raised in Guadalajara and graduated as an engineer from the city’s Escuela Libre de Ingenieros in 1923. During an extensive trip to Europe and Morocco, Barragán heard lectures by Le Corbusier and became familiar with the ideas and work of Ferdinand Bac. Inspired by their modernist approach, he returned to Guadalajara in 1926, where he initially worked alongside his brother—Juan José (who had worked with Birger Winsnes as an engineer building the La Capilla-Chapala railroad line and who later developed a close business association with Castellanos Lambley)—before establishing his own architectural practice.

In 1936, after about a decade of projects in Guadalajara and Chapala, Luis Barragán moved to Mexico City, where he designed and developed the residential area of Jardines del Pedregal. His house and studio, completed in 1948, are now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Barragán was also responsible, with partners, for Torres de Satélite (1957) and the residential areas of Las Arboledas and Lomas Verdes, all in the proximity of Ciudad Satélite in the state of México.

In his seventies, Barragán was granted a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (1976) and won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize (1980), the only Mexican ever to do so.

Following his death in 1988, Barragán’s ashes were interred in the Rotunda de los Jaliscienses Ilustres in Guadalajara. In a macabre twist, some of his ashes were later turned into a diamond ring by American conceptual artist Jill Magid, whose documentary, The Proposal, details her bizarre attempt to exchange the ring for the Barragán archives, currently in private hands in Switzerland, and repatriate them to Mexico.

Here is a list of proven or suspected Barragán works in Chapala, as well as some Barragán proposals that were never acted upon:

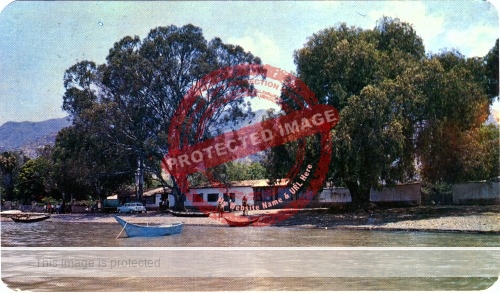

Casa Barragán (aka the Bynner house), Chapala, 2016. Photo: Tony Burton.

1. Avenida Madero #411 (Casa Barragán, aka the Witter Bynner house)

A few buildings north of the main church, and on the same side of Avenida Madero, Casa Barragán had belonged to the Barragán family, who owned a hacienda in the hills on the south side of the lake, since the end of the nineteenth century. The family used their Chapala house as a staging point on trips to and from Guadalajara. In 1931-32, Luis Barragán, ably assisted by colleague Juan Palomar y Arias, transformed the original residence here into an interesting two-story modernist home. Eight years later, Casa Barragán was bought as a vacation home by the American poet Witter Bynner. Though the house has been remodeled several times since, including by Bynner—who installed large windows in his study and added a rooftop mirador to get a view of the lake—it retains several distinctive Barragán design elements.

2. Avenida Madero #232

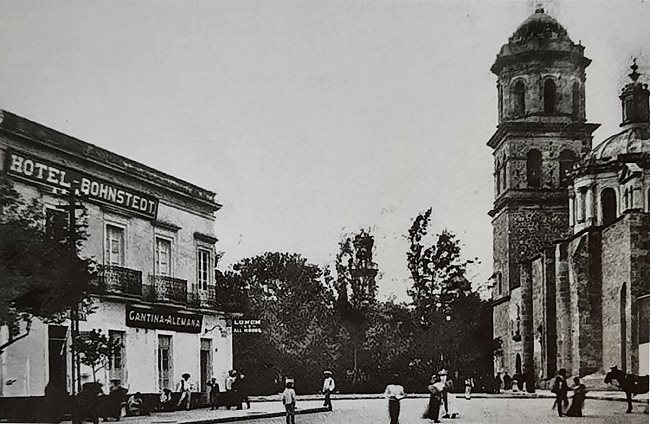

Definitive attribution of this building to Luis Barragán is, as yet, unproven. At the end of the nineteenth century, this property was the site of a rustic inn called Mesón de la Purisima. In April 1932, when Luis Barragán and his siblings were settling their father’s estate, five of the six siblings—engineers Juan José and Luis, lawyer Daniel, and their two sisters, Luz and Paz—sold Mesón de la Purísima to their brother, Alfonso. Three years later, in October 1935, when Alfonso sold it to Carlota Bohnstedt de Monteverde, the new deed stated that the original building had been torn down and replaced by a new house. It seems fairly likely, in my opinion, that this would have been designed by Luis Barragán, perhaps assisted by his brother Juan José. This property, remodeled more than once since the 1930s, became the Plaza Hotel Chapala in 2019.

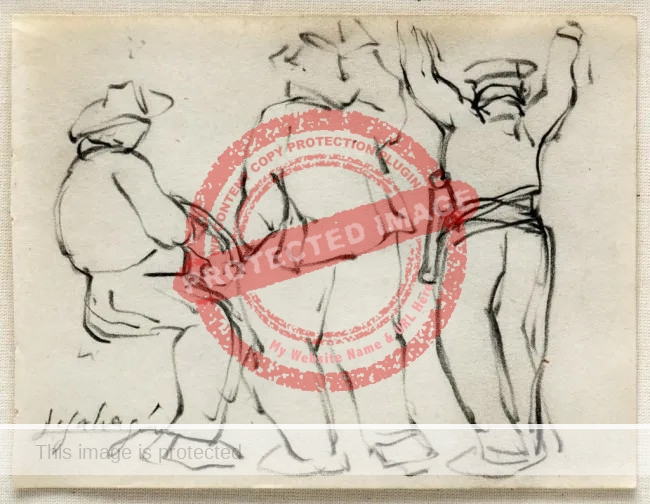

Sketch by Luis Barragán for Casa Newton. (Federica Zanco: “Luis Barragán: la revolución callada,” p 55)

3. Avenida Hidalgo #250 (Villa Niza, later known as Casa Newton)

This elegant residence, dating from 1919, was originally designed by Guillermo de Alba for Andrés Somellera, a Guadalajara businessman. Its strong geometric design boasts only minimal exterior ornamentation. The ideas proposed in 1934 by Luis Barragán (sketch above) were never carried out.

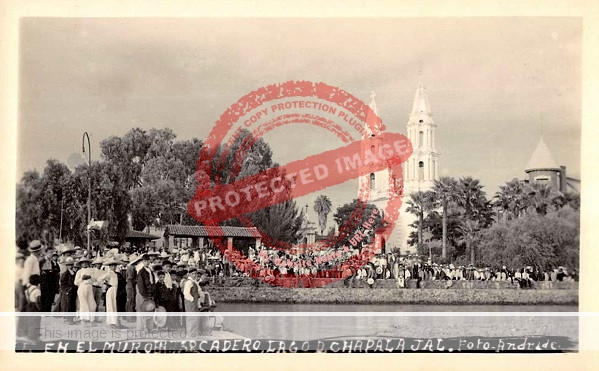

4. Kiosk, Central Plaza

In that same year, 1934, Barragán designed a new kiosk (below) for the main plaza in Chapala, then located about a block south of the current central plaza. Though I’ve never seen any supporting documentary evidence (beyond a brief mention in Barragan: The Complete Works), the kiosk was apparently constructed and installed. The original plaza was relocated during the extensive remodeling of the town center at the end of the 1940s. The kiosk was not installed in the new plaza, and its current whereabouts, if it survived, are unknown.

Barragan. 1934. Design for Chapala kiosk. (Credit: Raúl Rispa, et al, 2003)

5. Paseo Ramón Corona #10

Guadalajara architect Juan Palomar Verea (grandson of Juan Palomar y Arias, who worked closely with Luis Barragán on the transformation of Casa Barragán) has identified this building (sandwiched between two properties remodeled by Pedro Castellanos Lambley in the 1930s) as a project undertaken by Barragán in about 1934 for Gustavo R Cristo, a former mayor of Guadalajara. Numerous renovations since mean that few signs, if any, of Barragán’s input remain today.

6. Paseo Ramón Corona #14 (Villa Robles León)

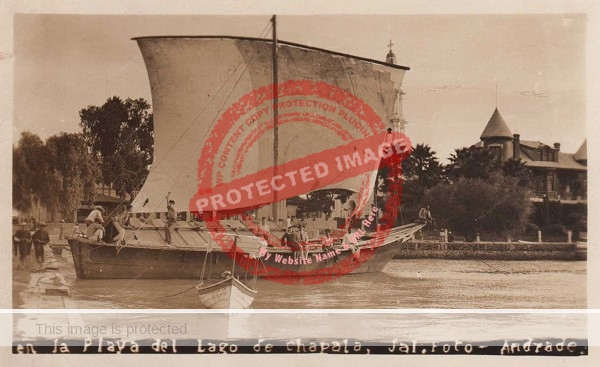

Villa Robles León, which still stands, was an existing older building remodeled in a joint project in the 1930s by Luis Barragán and Ignacio Díaz Morales into a modernist residence, readily identifiable by its highly distinctive rounded sides. It was the vacation home (looking directly onto the beach at the time) of Emiliano Robles León (1888–1961), a notable lawyer, notary and academic in Guadalajara. Barragán made extensive changes and added a third story to create the equivalent of a master bedroom (with its own bathroom) on the top level. Unlike most homes in Chapala, the arched entrance way to the property is positioned off-center at one extremity of its southern boundary wall, a wall made of long, thin bricks arranged as a series of “V”s forming a geometric wave design. Several aspects of Barragán’s redesign were apparently inspired by a boat.

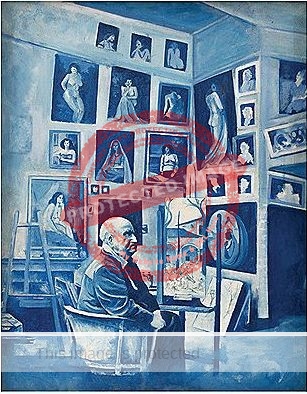

Casa de las Cuentas, 1941. (Credit: Goldsmith, 1941)

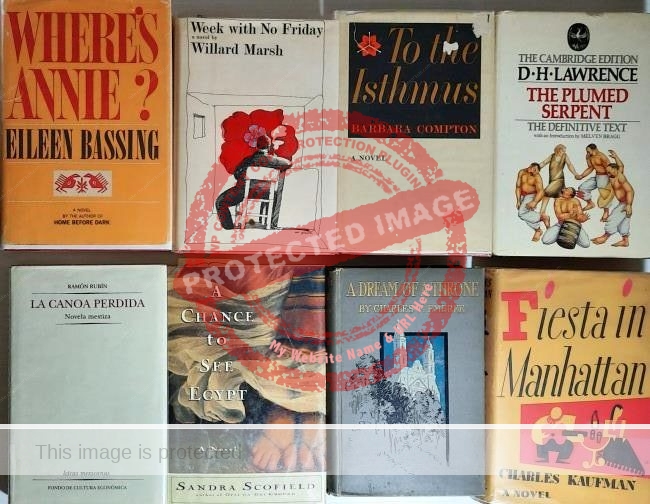

7. Calle Zaragoza #307 (Casa de las Cuentas, aka the D. H. Lawrence house)

Casa de las Cuentas is where D. H. Lawrence resided for a few weeks in 1923 while writing the initial draft of The Plumed Serpent. This originally nineteenth century residence was remodeled by Barragán in about 1940, when it was owned by Gustavo R. Cristo. Barragán’s work here was featured the following year in House and Garden. His striking “halfmoon entrance gateway, with heavy wooden grill work painted red outside and French blue inside” added an Oriental touch, characteristic of much of his work of this period. He also designed a spectacular rounded bay window for the dining room, with built-in steel shelves for a collection of hand-blown glass. The house was since been extensively remodeled more than once, gathering links to several other famous writers and artists along the way. Today, it is the Hotel Villa QQ.

8. Avenida Hidalgo #251 (Jardín del Mago)

Almost opposite Villa Niza is Jardín del Mago, a small residence nestled in a terraced garden. A stone dog guards the gate of this interesting property. The unpretentious house and garden, thought to date from about 1940, has a close link to Luis Barragán: it was the Chapala vacation home of his sister Luz and her husband, Alfredo Vázquez Tello, an architect turned antiquities dealer based in Guadalajara. Architect Juan Palomar Verea believes that Luis Barragán personally oversaw the creation of this garden with its extensive terraces and plantings covering around 5000 square meters of the lower slopes of Cerro San Miguel, and it is possible that Barragán also had some input into the simple, functionalist, multilevel residence. Palomar considers this is “one of the most important Mexican gardens of all time,” and represents a key link in style and date between the gardens of Ferdinand Bac (under whom Barragán studied in Europe in 1922) and Barragán’s own internationally acclaimed Jardines del Pedregal de San Ángel (1948) in Mexico City. If Palomar is correct, the Jardin del Mago shows how Barragán, even early in his career, had already begun to develop the individual style that would later lead to world fame.

9. Avenida Hidalgo #246 (Villa Adriana)

Villa Adriana, designed by Pedro Castellanos Lambley, was completed by Luis Barragán in about 1947 for its then owners: Jesús González Gallo (Jalisco state governor, 1947–1953) and his wife, Paz Gortázar (sister of María Luisa Gortázar, the wife of Luis’s brother Alfonso). This magnificent building, created by two of the region’s most famous architects, has been impeccably maintained to this day.

10. Subdivision of a lot on Calle Guerrero (1963)

Along with #1, #3 and #7, this is one of four Barragán projects in Chapala included on the List of Works published by The Barragán Foundation, based in Switzerland. The Curator of the Foundation, Martin Josephy, kindly responded to my email query about this entry to explain that it comprised “a small number of variants for the subdivision of a plot of ca. 1500 square meters along Calle Guerrero.” While its precise location remains to be determined, there is no evidence that this project was ever carried out.

Most existing listings of the ‘complete works’ of Luis Barragán, Mexico’s greatest twentieth century architect, clearly need to be revised to reflect the rightful place of Chapala in the history of Mexican architecture!

Note: Despite its name, the location of the hotel-restaurant named “Casa Barragán,” (Paseo Ramón Corona #13, Chapala) has no known connection to the architect. This property was originally the site of the distinctive two-story Villa Carmen, built by Roberto de la Mora in the final decade of the nineteenth century; its later names included Villa Margarita and Villa Sergio. The original building was demolished prior to the 1950s.

Six chapters of If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants —translated into Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes— relate to residences designed or modified by Luis Barragán. They include more detailed accounts of Casa Barragán (the Witter Bynner house), Villa Adriana, Villa Niza (Casa Newton), Jardín del Mago, Villa Robles León and Casa de las Cuentas (D.H. Lawrence house).

Sources

- Anon. 1935. “Recent Work of a Mexican Architect- Luis Barragán.” Architectural Record (New York), January, 1935, 33-46.

- Jose Alvarez Checa, Luis Barragan, Manuel Ramos Guerra. 1991. Obra construida. Luis Barragán Morfín. 1902-1988. Sevilla, Spain: Junta de Andalucía. Consejeria de Obras Publicas y Transportes.

- Goldsmith, Margaret O. 1941. “Week-end house in Mexico.” House and Garden, vol 79 (May 1941), 44-45.

- Rispa, Raúl and Antonio Toca. 2003. Barragan: The Complete Works. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Palomar Verea, Juan. 2019. “Chapala: primera de las cuatro casas que Luis Barragán hizo para sí mismo.” El Informador, 10 July 2019.

- Zanco, Federica. 2014. Luis Barragán: la revolución callada. SKIRA.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.