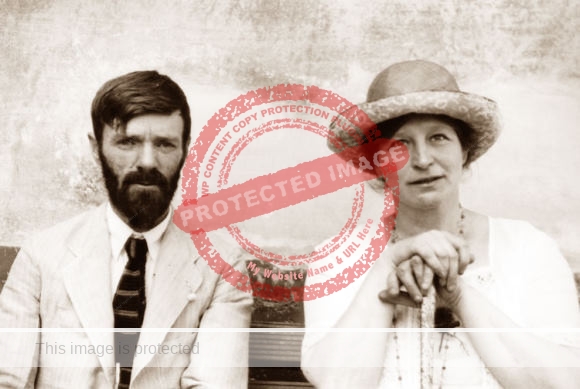

English novelist, poet and essayist David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930) was 37 years of age in summer 1923 when he spent three months in Chapala writing the first draft of the work that eventually became The Plumed Serpent (1926).

Early years

Lawrence was born in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, England, on 11 September 1885, and died in France on 2 March 1930. He studied at Nottingham High School and University College, Nottingham, where he gained a teaching certificate, and then taught for three years, but left the profession in 1911, following a bout of pneumonia, to concentrate full-time on his writing career. In 1914, he married Frieda Weekley (née von Richthofen) (1879-1956), the former wife of one of his university French teachers.

Lawrence was deemed medically unfit to serve in the first world war (1914-18). During the war, the couple lived in near destitution on account of suspicion engendered by Lawrence’s anti-war sentiments and Frieda’s German background. Accused of espionage while living at Zennor, on a secluded part of the Cornish coast, they were forced to move to London.

As soon as was practical after the war, they left the U.K. to live abroad. Lawrence only ever returned to the U.K. on two occasions after that, each time staying for as short a time as possible. Lawrence and Frieda began an itinerant existence as the novelist sought the perfect place to live and work; this quest took them to Australia, Italy (where he acquired the nickname Lorenzo, used by wife Frieda and others from that time), Sri Lanka, the U.S., Mexico and France, but no single location ever satisfied Lawrence for long.

From New Mexico to Mexico City and Chapala

In September 1922, Lawrence and Frieda were invited by Mabel Dodge Luhan, to spend the winter in New Mexico. En route to her ranch near Taos, they spent a night in Santa Fe at the home of Witter Bynner the poet. Bynner and his secretary (and lover) Willard (“Spud”) Johnson would travel with the Lawrences to Mexico the following year. (We look at them in relation to Lake Chapala in separate posts).

In March 1923, Lawrence, Frieda, Bynner and Johnson arrived in Mexico City and took rooms in the Hotel Monte Carlo, close to the city center. This hotel became the basis for the Hotel San Remo in The Plumed Serpent.

By the end of April, Lawrence was getting restless again, and still looking for somewhere to write. The party had an open invitation to visit Idella Purnell, a former student of Bynner, in Guadalajara. Lawrence read about Chapala in Terry’s Guide to Mexico and, taking into account its proximity to Guadalajara, decided to explore the village for himself.

Curiously, there is some uncertainty among biographers as to how (and precisely when) Lawrence first arrived in Chapala. It is usually claimed that he left the Mexico City-Guadalajara train at Ocotlán, stayed at the Ribera Castellanos hotel, and then took a boat to Chapala. This version is given by Clark (1964)—who specifies that Lawrence left the hotel and arrived in Chapala on 29 April—and by Bynner in Journey with Genius (p 124), and this manner of arrival was clearly the basis for the trip to “Lake Sayula” described in chapters V and VI of The Plumed Serpent.

However, it has been claimed elsewhere that the house Lawrence subsequently rented in Chapala was recommended to him by a consular official in Guadalajara. If that is true, it seems more likely that Lawrence met the official face-to-face in Guadalajara. He would then have had several alternative ways to reach Chapala: by train back to Ocotlán, followed by boat; or by train to La Capilla and then the La Capilla-Chapala railway (which operated on a limited schedule); or by bus (camion) all the way from Guadalajara.

However he arrived, Lawrence liked what he saw and, within hours of arrival, sent an urgent telegram back to Mexico City pronouncing Chapala “paradise” and urging the others to join him there immediately.

Frieda, Bynner and Johnson narrowly caught the overnight train and met the Purnells in Guadalajara the following morning. According to Bynner, Frieda then caught a camion (bus) to Chapala to join her husband, who had already rented a house in Chapala, at calle Zaragoza #4 (later renumbered #307). Lawrence told Bynner by letter that the house was ‘pleasant,’ belonged to the Hotel Palmera, and was near the first corner after Villa Carmen. The manager of the Hotel Palmera at the time was an Italian hotelier, Antonio Mólgora, and a 1919 map shows that Mólgora owned the house on calle Zaragoza. The Italian connection probably appealed to Lawrence, who had lived in Italy a few years earlier.

Bynner and Johnson opted to stay a few days in the city before joining the Lawrences at the lake. When they did arrive, they chose to enjoy the comforts of the nearby Hotel Arzapalo.

Lawrence sets up home in Chapala

Lawrence and Frieda soon established their home for the summer in Chapala, at Calle Zaragoza #4 (later renumbered #307). In a letter back to two Danish friends in Taos, Lawrence described both the house and the village:

“Here we are, in our own house—a long house with no upstairs—shut in by trees on two sides.—We live on a wide verandah, flowers round—it is fairly hot—I spend the day in trousers and shirt, barefoot—have a Mexican woman, Isabel, to look after us—very nice. Just outside the gate the big Lake of Chapala—40 miles long, 20 miles wide. We can’t see the lake, because the trees shut us in. But we walk out in a wrap to bathe.—There are camions—Ford omnibuses—to Guadalajara—2 hours. Chapala village is small with a market place with trees and Indians in big hats. Also three hotels, because this is a tiny holiday place for Guadalajara. I hope you’ll get down, I’m sure you’d like painting here.—It may be that even yet I’ll have my little hacienda and grow bananas and oranges.” – (letter dated 3 May 1923, to Kai Gotzsche and Knud Merrild, quoted in Merrild.)

Lawrence’s stay at Lake Chapala proved to be a highly productive one. His major achievement at Chapala was to write the entire first draft of a new novel set in Mexico. Initially called Quetzocaoatl (after the feathered serpent of Mexican mythology), the draft was completely rewritten the following year in Oaxaca as The Plumed Serpent.

Writing beside the beach

After a couple of false starts, Lawrence began his novel on 10 May and, writing at a furious pace, completed ten chapters by the end of the month. Within two months, the first draft was essentially complete.

Lawrence did not do very much writing in the house, but preferred to sit under a tree on the edge of the lake. Willard “Spud” Johnson recalled that:

Mornings we all worked, Lawrence generally down towards a little peninsula where tall trees grew near the water. He sat there, back against a tree, eyes often looking over the scene that was to be the background for his novel, and wrote in tiny, fast words in a thick, blue-bound blank book, the tale which he called Quetzalcoatl. Here also he read Mexican history and folklore and observed, almost unconsciously, the life that went on about him, and somehow got the spirit of the place. There were the little boys who sold idols from the lake; the women who washed clothes at the waters’ edge and dried them on the sands; there were lone fisherman, white calzones pulled to their hips, bronze legs wading deep in the waters, fine nets catching the hundreds of tiny charales: boatmen steering their clumsy, beautiful craft around the peninsula; men and women going to market with baskets of pitahayas on their heads; lovers, even, wandering along the windy shore; goatherds; mothers bathing babies; sometimes a group of Mexican boys swimming nude off-shore instead of renting ugly bathing-suits further down by the hotel. ..Afternoons we often had tea together or Lawrence and I walked along the mud flats below the village or along the cobbled country road around the Japanese hill—or up the hill itself. We discovered that botany had been a favorite study of both of us at school and took a friendly though more or less ignorant interest in the flora as we walked and talked. Lawrence talked most, of course. (quoted in Udall)

Seeking a permanent home

For much of their stay in Chapala, Lawrence was hoping to find a property suitable for long-term residence, as evidenced by this letter, dated 17 June 1923, from Frieda to their Danish artist friends Knud Merrild and Kai Gøtzsche back in Taos, New Mexico:

“We are still not sure of our fate–but if we see a place we really like, we will have it and plant bananas–I am already very tired of not doing my own work.–Lawrence does not want to go to Europe, but he is not sure of what he wants. –The common people are also very nice but of course really wild–And I think we could have a good time, Merrild would love the lake and swimming, we could have natives to spin and weave and make pottery and I am sure this has never been painted—–” (quoted in Merrild)

It is unclear whether or not Frieda intended the last comment, about the lake never having been painted, to be taken literally. The truth is that many artists had painted Lake Chapala long before the Lawrences ever stayed there, including Johann Moritz Rugendas (who painted there in 1834), Ferdinand Schmoll (1879-1950), watercolorist Paul Fischer, and August Löhr (1843-1919). Moreover, only days after the Lawrences left their home in Chapala, it was rented by two young American artists, Everett Gee Jackson and Lowell Houser.

Late in June, Lawrence himself writes to Merrild, explaining that despite looking for a new home, they have now given up hope of finding somewhere suitable:

“We were away two days travelling on the lake and looking at haciendas. One could easily get a little place. But now they are expecting more revolution, & it is so risky. Besides, why should one work to build a place & make it nice, only to have it destroyed.

So, for the present at least, I give it up. It’s no good. Mankind is too unkind.” (quoted in Merrild)

In July 1923, a few days before Lawrence and Frieda left Chapala, they arranged an extended four-day boat trip around the lake with friends including Idella Purnell and her father, Dr. George Purnell. The trip, aboard the Esmeralda, began on 4 July. Two of the party returned early, but the others endured some very rough weather, before their return to port.

Lawrence returns to Chapala (briefly) in October 1923

On 9 July, the Lawrences left Chapala for New York via Guadalajara, Laredo, San Antonio, New Orleans and Washington D.C. The following month, Frieda went to Europe, leaving Lawrence behind in the U.S. In October, Lawrence returned to Mexico, traveling with the Danish painter Kai Gotzsche down the west coast, with plenty of unanticipated adventures, to spend a month in Guadalajara. They stayed most of the time in the Hotel García (where Winfield Scott, former manager of the Hotel Arzapalo in Chapala, was now in charge). From Guadalajara, they visited Chapala for a single day on 21 October 1923, before traveling to Mexico City in mid-November, before sailing from Veracruz for England.

The following year (1924), Lawrence and Frieda came back across the Atlantic to New Mexico in March, bringing with them the painter, the Hon. Dorothy Brett (who later wrote her own memoir of Lawrence). The Lawrences returned to Mexico in October 1924 and spent the Fall of 1924 in Oaxaca, where Lawrence focused on reworking Quetzacoatl into the manuscript for The Plumed Serpent. The Lawrences left Mexico in February 1925. They did not revisit Chapala during this trip.

The lake looks like urine?

Did Lawrence really like Lake Chapala? That remains an open question, and no doubt depended on his mood when asked. Playwright Christopher Isherwood, when interviewed by David Lambourne, credited D. H Lawrence with having taught him that for best effect you don’t need to describe things as they are, but as you saw them:

“Lawrence… was so intensely subjective. I mean his wonder at the mountains above Taos, you know, and then his rage at Lake Chapala. And the characteristic methods of his attack were so marvelous. I mean, he was in a bad temper about Lake Chapala, so he just said, ‘The lake looks like urine.’ He meant, ‘It looks like urine to me,’ you see…”

Lawrence Myths

Inevitably, many misconceptions have arisen about Lawrence’s time in Chapala. It is often assumed, for instance, that he spent far more time in Chapala than just ten weeks. It is sometimes claimed that he spent “one winter” there, whereas in fact he visited from May to July, witnessing the very end of the dry season and the start of the rainy season.

Nor was Lawrence the first Anglophone writer to find inspiration at Lake Chapala, though he was quite possibly the most illustrious. The honor of writing the earliest full-length novel set at the lake in English goes to Charles Embree (1874-1905), who spent eight months in Chapala in 1898, and wrote A Dream of a Throne, the Story of a Mexican Revolt (1900).

Chapala remains a place of pilgrimage for Lawrence fans

Since 1923, many Lawrence fans have made their own pilgrimage to Chapala to see first-hand what inspired their great hero. Perhaps the most famous of these admirers is the Canadian poet Al Purdy, who visited Chapala several times in the 1970s and 1980s. Purdy was a huge fan of Lawrence, even to having a bust of Lawrence on his hall table back in Canada and wrote a limited edition book, The D.H. Lawrence House at Chapala (The Paget Press, 1980).

- Lawrence: “The Plumed Serpent” (novel)

- D. H. Lawrence’s four-day boat trip around Lake Chapala

- Quinta Quetzalcoatl, the D. H. Lawrence house at Lake Chapala

To learn more about what Lake Chapala was like when Lawrence visited, see (a) If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants (Spanish: Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes), (b) Lake Chapala: A Postcard History and (c) Hotel Ribera Castellanos and the Lake Chapala Agricultural and Improvement Company.

Sources / Further reading:

- David Bidini. 2009. “Visit to poet Al Purdy’s home stirs up more than a few old ghosts,” National Post, 30 October 2009.

- Witter Bynner. 1951. Journey with Genius. New York: John Day.

- L. D. Clark. 1964. Dark Night of the Body: D. H. Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent. University of Texas.

- David Ellis. 1998. D. H. Lawrence: Dying Game 1922-1930; The Cambridge Biography of D. H. Lawrence, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press.

- David Lambourne. 1975. “A kind of Left-Wing Direction”, an interview with Christopher Isherwood” in Poetry Nation No. 4, 1975. [accessed 2 Feb 2005]

- D. H. Lawrence. 1926. The Plumed Serpent.

- Frieda Lawrence (Frieda von Richthofen). 1934. Not I, But the Wind… New York: Viking Press.

- Knud Merrild. A Poet and Two Painters: A Memoir of D. H. Lawrence.

- Harry T. Moore (ed). 1962. The Collected Letters of D. H. Lawrence (two volumes).

- Harry T. Moore and Warren Roberts. 1966. D. H. Lawrence and his world. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Edward Nehls (ed). 1958. D. H. Lawrence: A Composite Biography. Volume Two, 1919-1925. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Vilma Potter. 1994. “Idella Purnell’s PALMS and Godfather Witter Bynner.” American Periodicals, Vol 4 (1994), pp 47-64. Ohio State University.

- Warren Roberts, James T. Boulton and Elizabeth Mansfield (eds). 1987. The letters of D. H. Lawrence, Vol 4: June 1921 to March 1924. Cambridge University Press.

- Sharyn Udall. 1994. Spud Johnson & Laughing Horse. (Univ. New Mexico)

Comments and corrections welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

excellent account. great reading and very helpful with some work I’m doing on Lawrence in Mexico. Gracias!

Mark, you are most welcome. Let me know if you need any further information about Lawrence at Lake Chapala. The blog posts are only a summary of the material I am working on.

Thank you Tony, this was very helpful for my Lawrence research!

Frances, you are most welcome. Let me know if you have specific questions that weren’t answered in my pieces about Lawrence at Chapala, and I’ll see if I can help further.