Ajijic’s sister city connection to Studio City in California had already been going five years by the time journalist Bill Reed wrote about it in 1967. The sister city program was part of the People to People initiative begun a decade earlier by former US president Dwight D. Eisenhower.

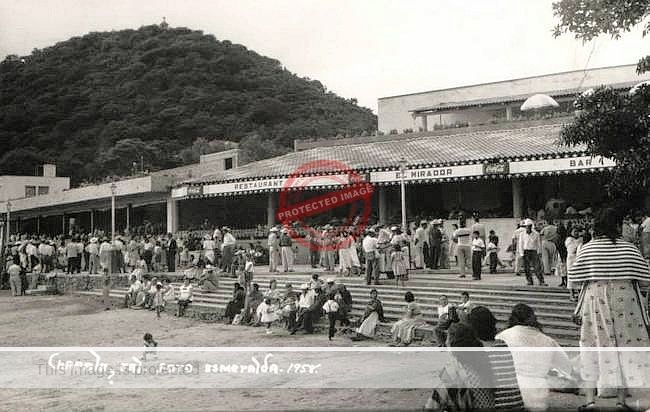

In 1964 the executive board of People to People held a lunch meeting at the Villa Montecarlo in Chapala, a meeting attended by Eisenhower’s son (John D. Eisenhower), Mexican President Adolfo López Mateos, former president Miguel Alemán, the Jalisco state governor Juan Gil Preciado, and other guests who listened to a keynote address by Walt Disney (in which he claimed “Jalisco” was his favorite song).

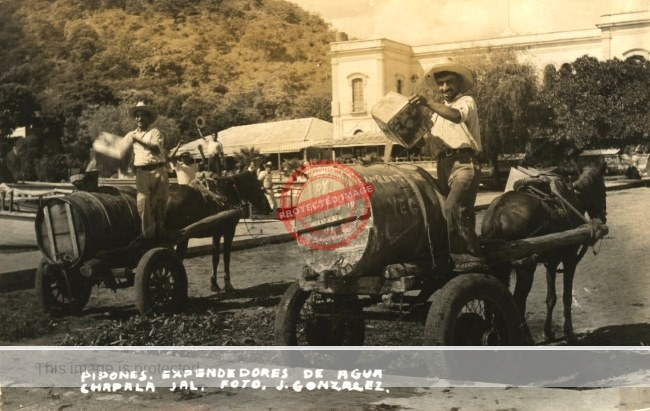

According to the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (in January 1963), the idea to twin Ajijic and Studio City came from Eric Lindhe, a retired US Army colonel who had lived seven years in Ajijic and suggested the idea to Jim Hawthorne, Studio City’s honorary mayor. Lindhe undertook to liaise with villagers and help organize a formal sister city relationship. The press report also mentioned that a more recent Ajijic resident, retired civil engineer Don Savage, “has been working on a project to get water into the town’s homes for the first time.”

Press Telegram, 1962

The first tangible impact of the sister city connection was in September 1962 when a Studio City resident, the uncle of Ann Mosher, visited Ajijic and presented donated poster paints to the children taking art classes in Neill James’ library. That program grew into the Children’s Art Program, now held under the auspices of the Lake Chapala Society.

Mosher explained to fellow donors that the children made cards which tourists bought for a peso each, with part of the proceeds going direct to the aspiring young artists.

The Chamber of Commerce in Studio City had initially wanted to send medicines and children’s clothing to Ajijic, before learning that customs regulations might be an issue, so they sent large bottles of poster paint instead.

Despite knowing the potential problems, in October the Kiwanis Club in Studio City organized a major clothing drive for Ajijic children and collected close to a ton of clothes and shoes! Simultaneously, the Studio City Chamber of Commerce (SCCC) announced a 10-day tour to Mexico, to include Ajijic, Guadalajara, Mexico City, Taxco and Acapulco.

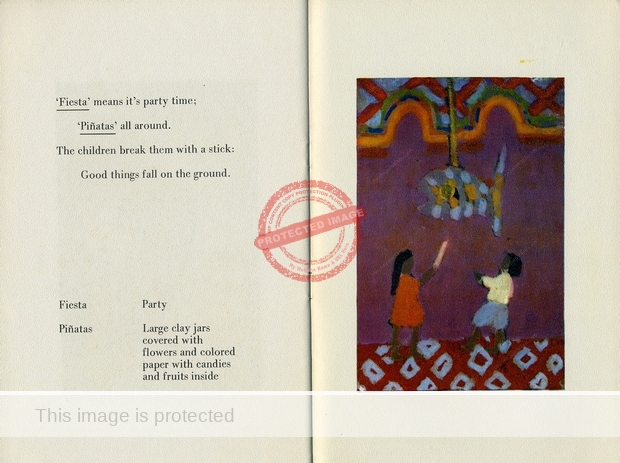

In November 1962 the Studio City Merchants Association joined with SSCC to host a Mexican Fiesta to raise funds, and at the end of month, thirteen Studio City residents left Los Angeles for Mexico. According to press reports, Mexicana airline assisted with the transportation of the donated clothing.

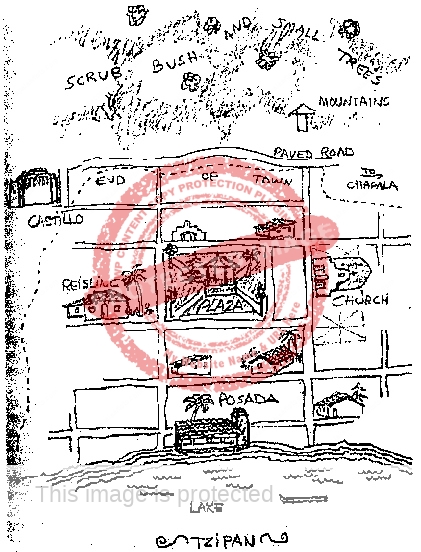

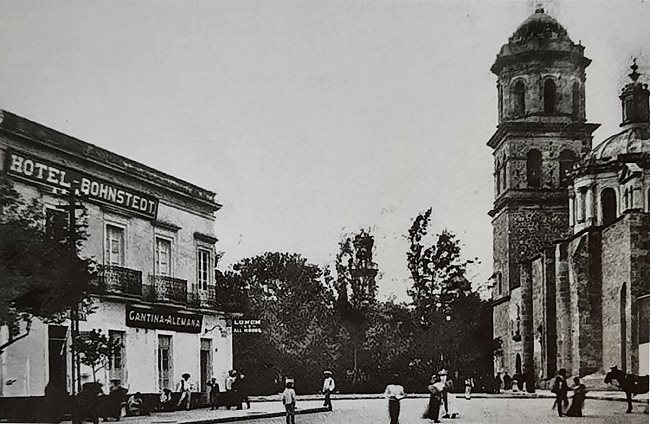

All thirteen visitors were overwhelmed by the “extraordinary cordiality of their hosts south of the border.” The group traveled to Ajijic from the airport in a “special bar-equipped bus.” Some sixty charros in multicolored serapes met the bus on the outskirts of Ajijic to escort the Studio City group to the plaza, where an estimated 4000 villagers gathered to cheer and welcome the group with music, folkloric dancing, church bells and confetti. “Torchlights blazed on all sides (there are no street lights in Ajijic).” This was the start of a three-day whirl of receptions, visits, parties and dancing. The visitors encountered no anti-US sentiments in the village, which “may be partly because the Americans residing in Ajijic have taken a special, helpful interest in the town and its problems.”

The following March the Los Angeles Times reported that plans were underway for a return visit by a group of Ajijic villagers to Studio City in April (via bus to Tijuana), and that Studio City residents had started to fund raise for a “long-needed” school in Ajijic, which “could be built for as little as $1,500.” This visit was subsequently postponed more than once, in part because a school teacher from Ajijic was acting as the group’s interpreter, so it needed to take place during a school holiday.

In April it emerged that the six large boxes of clothing that had been held at Guadalajara airport since the previous December had finally been granted duty-free status and had been released, following the personal intervention of the President, to Col. Eric Lindhe for onward transport to Ajijic.

Los Angeles Times, 23 July 1963.

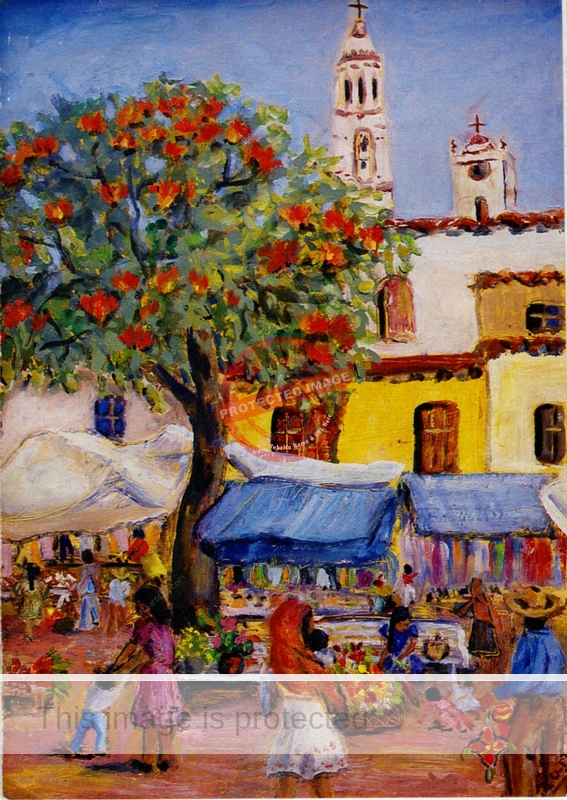

Fund raising continued apace in Studio City, including a Bowling Tourney for the “rehabilitation of a boys’ school” in Ajijic, and the auction of a Tink Strother oil painting of an Ajijic woman preparing tortillas. Strother had lived in Ajijic the previous year.

In July an “advance party,” comprised of Ajijic residents Don Savage and his wife, and their 22-year-old maid, Mariana Yañez (the niece of Ajijic mayor José Serna Flores), arrived in Studio City. Savage persuaded Studio City officials that any funds raised by SCCC to affray the expenses of a visit by Ajijic children could be far better utilized to help pay for the expansion of Saúl Rodilas Pina boys’ school in the village. The school, for grades 1 to 6, was attended by 400 boys at the time, and needed to expand but had run out of money. Villagers wanted to buy bricks and steel beams to add two classrooms and a kitchen. Savage pointed out to his SCCC hosts that the expense of obtaining passports and visas for Ajijic students would be considerable. The SCCC sent a check for $650.00 to Ajijic for the school and continued to fund raise. Eric Lindhe gave a talk in Studio City in December and raised a further $105.00 to outfit junior soccer teams in Ajijic.

In March 1964 the SCCC voted to provide $300.00 to bring two boys, two girls and two teachers from Ajijic to visit Studio City. At the end of the academic year, the Ajijic students finally arrived.

The four students named in newspaper reports were Rafael Chávez (13 years old), “Frederico” (Federico) López (11), María del Rosario Díaz (14) and María Guadalupe Reyes (13). They were chaperoned by teacher Martha Zuñiga (20) and school principal Velia Hugo. Born in Toledo, Ohio, Hugo had moved to Ajijic with her family as a 10-year-old and spoke perfect English. Also accompanying the group was delegado José Ramos Pérez and the village padre, Ramón Barba. Their Studio City hosts financed an itinerary that included visits to Disneyland, a beauty salon, shopping for clothes, a baseball game at Dodger’s Stadium, Revue Studio, boating and the naval air station at Long Beach. In their honor, Los Angeles mayor, Sam Yorty, officially proclaimed the week of July 9-16 “Ajijic Week in Studio City.”

Two years later a second group from Studio City, about 20-strong, stayed in Ajijic for several days at the end of November 1966. They toured the village boys’ and girls’ schools, and the new vocational school to which SCCC had contributed funds. By then, SCCC had plans to raise at least $1,000 to launch a food program of breakfasts for 200 needy Mexican youngsters in Ajijic. Blaine Hodgson, a retired US army officer living in Ajijic, had offered to oversee the program.

Velia Hugo kept in close contact with Studio City and the local newspaper reported in January 1968 that she was raising funds for a basketball court and that members of the SCCC also hoped to build a clinic in Ajijic, and start a kindergarten. A letter exchange was organized between students in Studio City and Ajijic, and in May the SCCC was planning to expand the small library in Ajijic and was considering establishing a retail outlet in Studio City to sell wares from Ajijic.

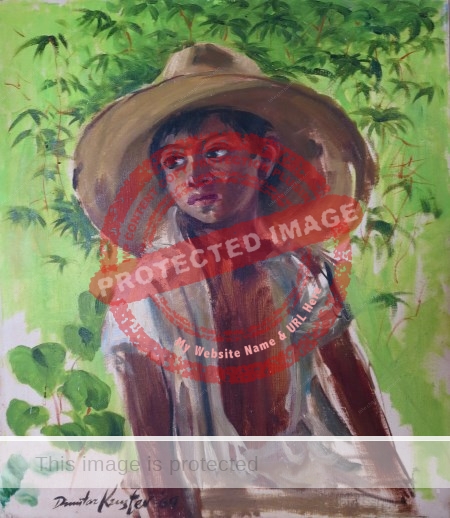

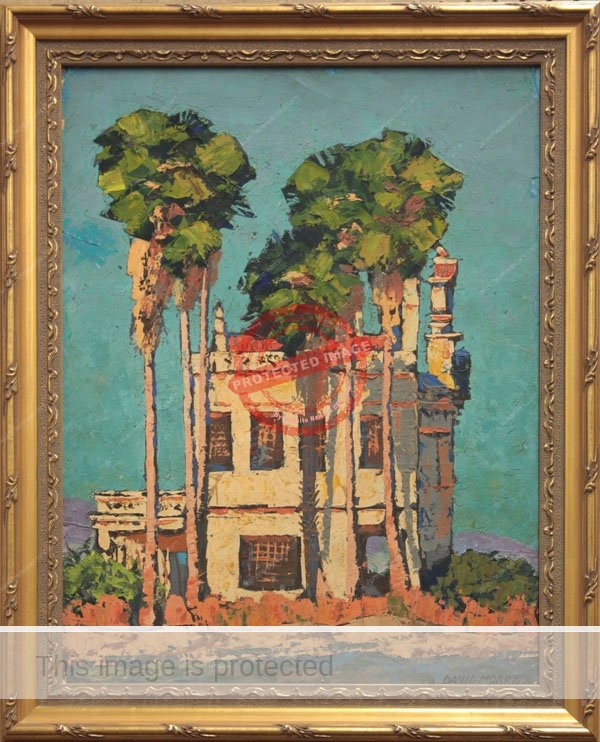

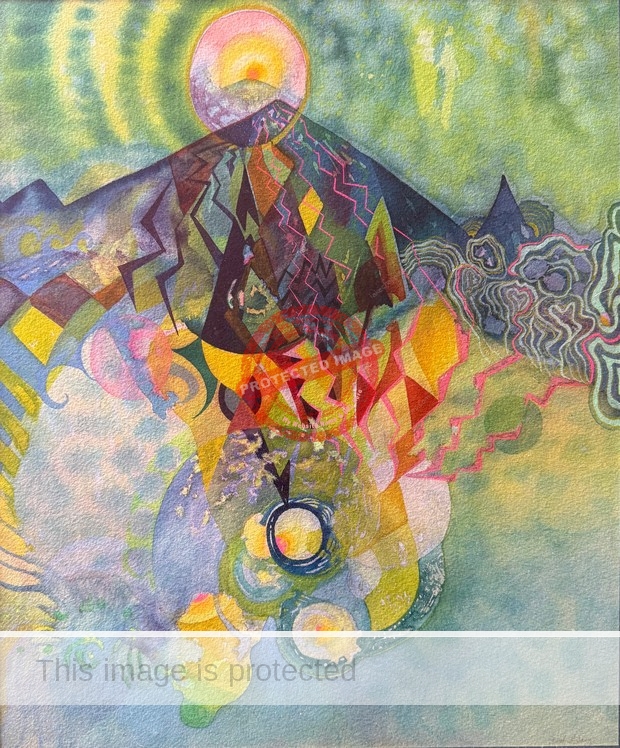

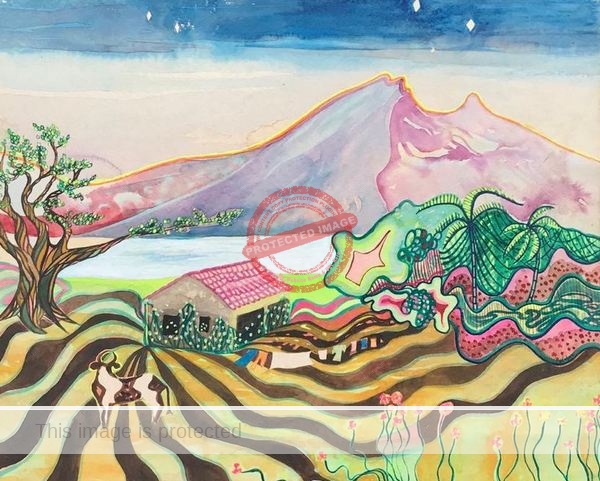

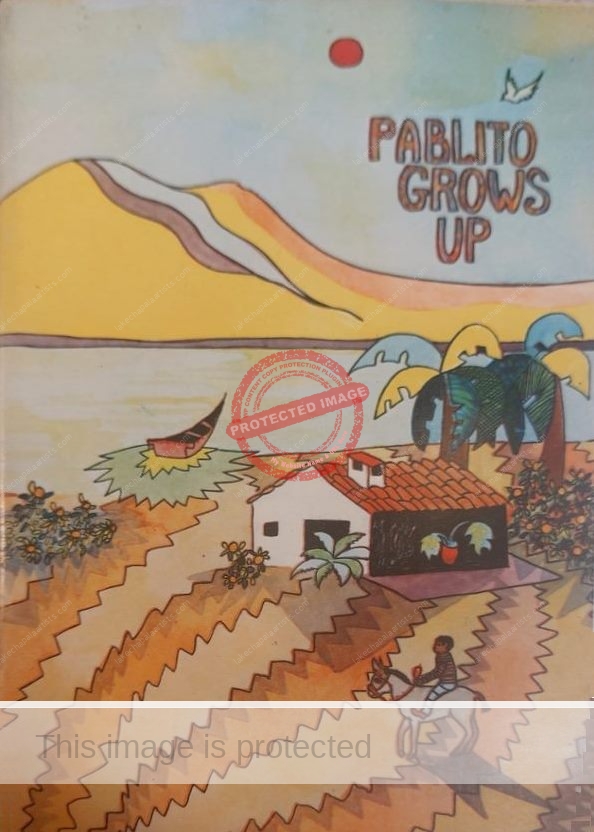

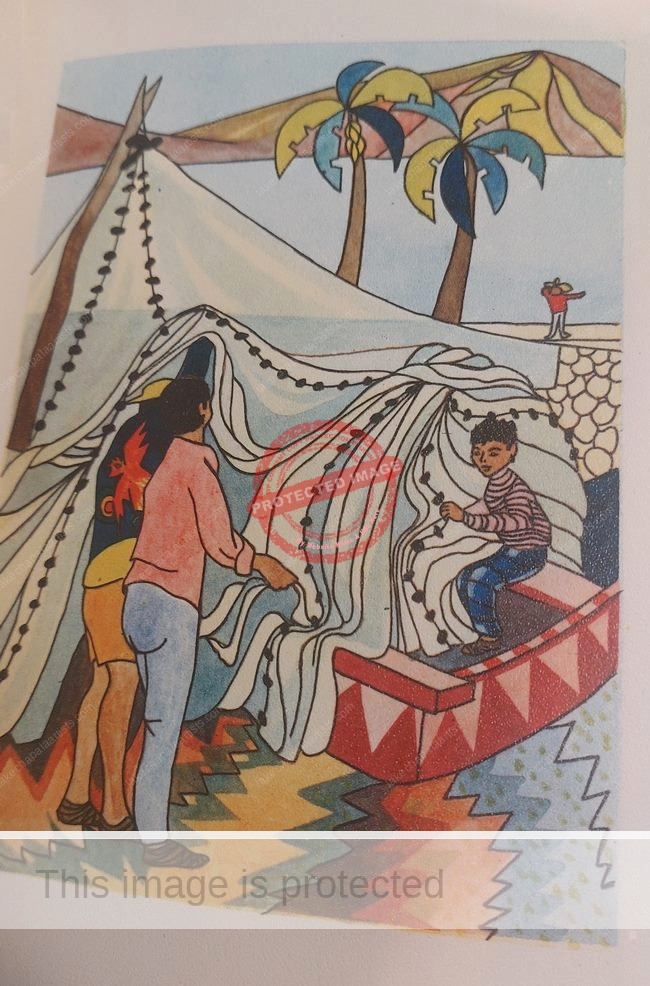

The SCCC also helped sponsor a 13-year-old Ajijic artist, Ramón Navarro, to leave Ajijic and live with an aunt in Los Angeles to take formal art classes. According to press reports, Navarro was, in August 1968, “exhibiting his oil paintings and watercolors at an art show in Guadalajara” and his talent had been discovered by Irma McCall, a former resident of Ajijic residing in Long Beach. (McCall’s article, “Ajijic–Paradise Under the Mexican Sun,” was published in the 11 March 1962 issue of the Independent Press-Telegram.) Studio City support for Navarro continued for several years. In 1973 the Women’s Division of SCCC gave him a scholarship to complete his education in the US.

The SCCC announced plans to invite Navarro and several residents of Ajijic to a block party in September. The Ajijic group was comprised of four adults—J. Trinidad Ramos Jr, president of the Ajijic Chamber of Commerce; businessman Rufino Palacios; Velia Hugo and Esperanza Briones, both teachers at the Girls’ School; and four 6th grader students: Rosemaría Jiménez (13), Antelma Plasencia (12), Rubén Romero (12) and Arnulfo Beas (13).

Velia Hugo addressed teachers at a luncheon at Riverside Drive Elementary school, telling them that, in Ajijic: “The number of children in our classes varies with about 100 children in first grade, 62 in fourth grade and 32 in sixth grade…. These children have only one teacher in each class.” She also explained that, with DIF support, hot breakfasts were being provided to about 500 village children.

J. Trinidad Ramos told the local press that after 6th grade in Ajijic, boys received “manual training” and girls studied sewing and dressmaking. He estimated that there were “more than 300 American families” living in the village, and stated that the resident Americans, spearheaded by Mr and Mrs Booth Waterbury of the Posada Ajijic, were interested in starting a medical center.

Studio City helped another young Ajijic artist in 1970 when the SCCC sponsored 24-year-old “Juan Olverez” (= Juan Olivarez) to study art for a month in Studio City. American artist Jack Rutherford, who had been living in Ajijic for several years and recognized the young man’s talent, had contacted the SCCC, which arranged for Olivarez to become the house-guest of Mr and Mrs Robert Hecker for the summer, while Mr and Mrs Rutherford and their four children enjoyed a working holiday in Laguna Beach.

- Note: Juan Olivarez was born in 1944 and would have been 26 in July 1970. Sadly he died in 2022 before I was able to ask him about his memories of Studio City and about his later artistic career, which centered on photography, as detailed in this profile.

As Ajijic grew, so contacts with—and financial support from—Studio City became more sporadic, though they continued until at least the mid-1980s. In 1971, for example educator Margaret Hyatt spent several days in Ajijic and returned later that year to give a month-long literacy tutor-training and demonstration course to young adults in Ajijic. A group of Studio City residents visited Ajijic in November 1973, to begin arrangements for a return trip for a 30-member delegation from Ajijic, including a youth soccer team, the following year. In 1976, SCCC organized the donation of medical equipment for Ajijic’s first public health clinic, which opened in May 1977. The SCCC also raised funds in 1977 for “school and church supplies” in Ajijic, and were still supporting a Scholarship Fund for Ajijic as late as 1984.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Several chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village offer more details about the history of Ajijic’s art community and its health and education facilities.

Note

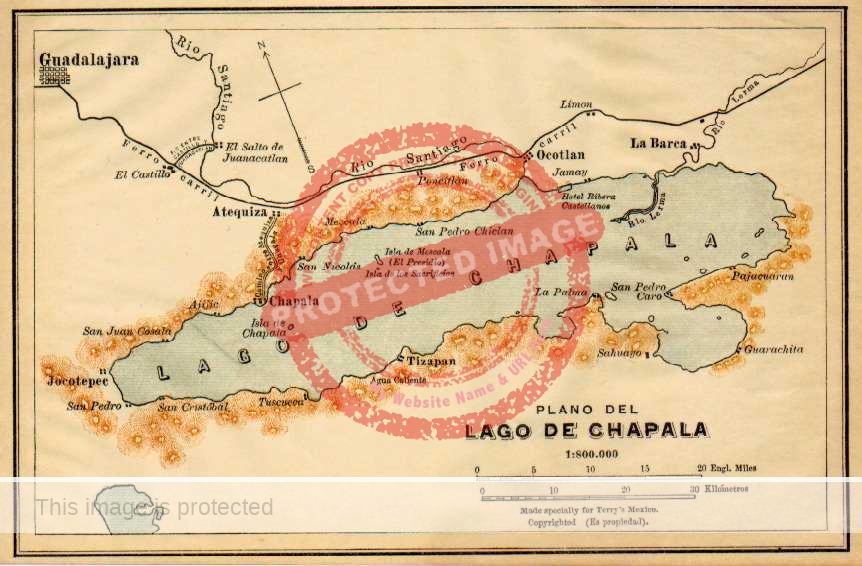

Other Lakeside communities with sister cities include:

- Chapala-Lake Arrowhead, California (included on official 1972 list of all sister cities)

- Jocotepec-Plymouth, California (begun 21 February 2014)

- Jocotepec-Watsonville, California (begun 15 September 2018)

- Chapala-Jin Xi, China (the highway through La Floresta was renamed Boulevard Jin Xi in 1994)

- Chapala-Barrhead, Alberta, Canada (from about 2007).

- Chapala-Pico Rivera, California (from June 2024)

Sources

- Guadalajara Reporter: 16 July 1964, 8; 1 March 2014, 7.

- Los Angeles Evening Citizen News: 19 Jan 1963, 4; 5 Dec 1963, 7; 3 Jul 1964, 6; 3 Jul 1964, 6; 13 Jul 1964, 6.

- Los Angeles Times: 7 Mar 1963, 138; 7 Apr 1963, 234; 15 Apr 1963, 2; 23 Jun 1963, 201; 4 Jul 1963, 107; 9 Jul 1963, 73; 27 Aug 1963, 2; 9 Jun 1964, 94; 31 Jul 1980, 209 12 Jul 1984, 211.

- Press-Telegram, 30 Sep 1962, 109.

- South Pasadena Journal: 03 Nov 1971, 10.

- Valley News: 07 Feb 1967, 99; 05 Jan 1967, 49; 29 Dec 1967, 15; 04 Aug 1968, 50; 20 Sep 1968, 35; 22 Sep 1968, 12; 04 Feb 1971, 90; 16 Nov 1973, 43; 08 Oct 1974, 25; 02 Sep 1976, 42; 31 Mar 1977, 35; 01 Nov 1977, 32.

- Valley Times, 2 Oct 1962, 15; 25 Oct 1962,17; 19 Nov 1962, 15; 27 Nov 1962, 2; 10 Jul 1964, 2; 25 Sep 1968, 8.

- Van Nuys News: 21 Jan 1968, 6; 09 May 1968, 49; 26 Jun 1970, 17; 30 Jun 1970, 13; 17 May 1973, 105; 07 Aug 1973, 12.

- Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet: 04 Jan 1966, 10; 04 Oct 1966, 47; 7 Oct 1962, 3.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

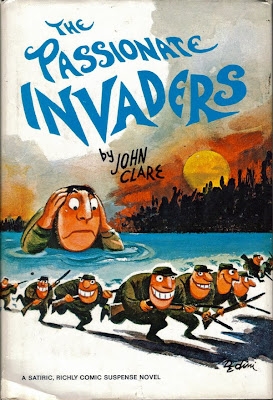

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’