Josefa, the fashion designer credited with showcasing Mexican styles on the world haute couture stage, lived and worked for many years at Lake Chapala. She successfully melded indigenous Mexican colors and elements with functional design to produce elegant and original dresses and blouses. Josefa designs were never mass-produced but made by local women in small villages near Guadalajara.

Josefa Ibarra and her business partner, Ana Villa, built up a brand known as El Aguila Descalza (The Barefoot Eagle). Based in Tlaquepaque, The Barefoot Eagle opened retail stores in several major Mexican cities and one in Boston, while simultaneously supplying numerous high-end department and fashion stores in the USA and elsewhere.

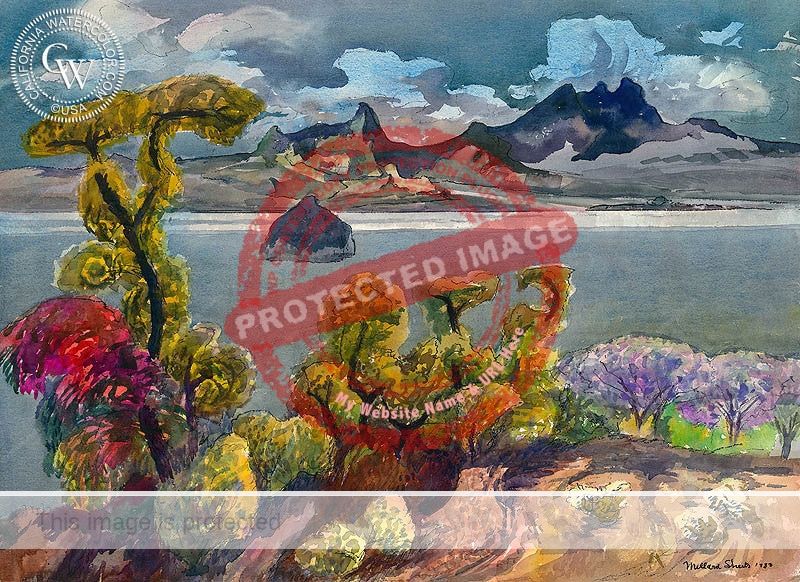

Design by Josefa

Josefa followed her own intuition as regards fashion and her success resulted from a series of serendipitous encounters. Her first lucky break came while she was living in Puerto Vallarta in the late 1950s. Josefa and her husband, Jim Heltzel, lived near the beach in a thatched hut, from where Josefa sold jewelry made of coconuts and seashells. The couple’s hippie lifestyle extended to Josefa designing and making her own dresses and beachwear.

Walking along the beach one day in 1959, Josefa struck up a conversation with Chris and Lois Portilla. They were far more interested in the clothes she was wearing than her jewelry and suggested that they help her market her dress designs. Lois, who remained friends with Josefa for decades, ran the ‘Latin Imports’ store at the Disneyland Hotel in California, and Josefa’s designs were soon being sold there.

Josefa began to make more designs and sell her creations to visiting tourists. Her second big break, in 1963, involved American superstar Elizabeth Taylor, who was visiting Puerto Vallarta, then only a small village, while Richard Burton was filming The Night of the Iguana, directed by John Huston and co-starring Ava Gardner.

One afternoon, in a break from filming, Taylor was with the cast and crew exploring the village when they came across a selection of beautiful dresses hanging from the branches of a tree outside a typical small hut. The visitors bought every last one of Josefa’s dresses and the famous American movie star subsequently added numerous additional Josefa designs to her wardrobe during her repeat visits to Puerto Vallarta over the next decade.

Even with Taylor’s support, it is unlikely that Josefa would have become as famous as she did had it not been for a third lucky break. This came when she was introduced by a friend, Lou Foote, to Boston-born Ana Konstandin Villa, who worked in Tlaquepaque alongside her husband, Edmondo Villa, for Arthur Kent, owner of El Palomar, the famous stoneware factory. Ana and her husband wanted to open their own retail store. Ana, a graduate of the Academy Moderne of Fashion in Boston, had an eye for style and was a buyer for the city’s Filene’s Department Store. Ana loved Josefa’s designs and realized that they presented a unique business opportunity. The two ladies got on famously together and their complementary skill sets ensured the success of The Barefoot Eagle, the Villas’ store in Tlaquepaque.

Journalist Sheryl Kornman who interviewed Josefa in 1970 found her just “as exciting, as articulate, as vivid as the costumes she designs.” Kornman described Josefa as casually dressed, wearing a “flimsy blue and red short shift” with her “long brown hair in a braid tossed forward over one shoulder,” and sandals on her feet. The designer said she had started by making jewelry in Puerto Vallarta a little more than a decade earlier before beginning to sew her own clothes and making some for friends. She then taught her “house girl” and others how to sew, and began to produce designs inspired by indigenous Huichol and Oaxacan handicrafts and art. At the time of Kornman’s interview, Josefa and her husband were living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, from where Josefa returned to Guadalajara at least twice a year, timing the visits to prepare for a summer line released in April and a fall/winter line released a few months later.

The Barefoot Eagle grew rapidly and became Mexico’s leading producer of internationally famous high fashion women’s apparel. Chris Adams (Ana Villa’s brother-in-law) provides a detailed case study of The Barefoot Eagle in his book, Up Your Sales in Any Economy. At its peak, the company employed several hundred women in three outlying villages near Guadalajara to undertake all the embroidery and decoration, with everything done by hand to maintain the artesanal quality. Most of the cotton fabric used came from Mexico City; the steadfast dyes were imported.

The Barefoot Eagle opened retail stores in several major Mexican cities: Acapulco, Cancún, Manzanillo, Mexico City, Puerto Vallarta, Monterrey, San Miguel de Allende, Tijuana, and Zihuatanejo. It also opened one in Boston’s famed Faneuil Hall Marketplace. Overseas stores that stocked Josefa designs included Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor and Macy’s, in addition to specialist boutiques in Denmark, England, the Netherlands and France.

The celebrity effect was contagious. Besides Elizabeth Taylor, those photographed wearing Josefa dresses or blouses included Lady Bird Johnson (who wore a Josefa dress for the cover of McCall’s magazine in August 1974), Glenda Jackson (in the movie A Touch of Class), Sophia Loren, Diana Ross, Loretta Young, Princess Grace of Monaco, Nancy Reagan, Deborah Kerr and Farah Diba, the wife of the former Shah of Iran. A Josefa-designed shirt was worn by Bo Derek’s onscreen husband in the Movie 10, which was filmed at Las Hadas in Manzanillo.

Josefa was, according to various sources, the first Mexican dress designer to have her work grace the cover of Vogue Paris. Interestingly, not long afterwards, another designer—Gail Michel de Guzmán—who lived at Lake Chapala at the same time as Josefa, had her own work featured in Vogue Paris.

According to Adams, Josefa considered it a compliment that she was the most copied designer in Mexico. Adams played a part in the commercialization of The Barefoot Eagle brand, producing a factsheet and sales pointers for all the salespeople in the various retail stores. Among other things, salespeople were instructed to ensure that prospective clients understood that even if they thought the items were pricey, they were definitely worth every centavo because they were hand-embroidered designer creations and works of art.

The Barefoot Eagle and Josefa’s brand continued to grow. Josefa was one of the first designers in Mexico to export on a large-scale. The extraordinary export success of Josefa was recognized by Mexico’s federal government which awarded her company a National Export Prize seven years in a row. With the sponsorship and support of the Mexican Embassy in the US, Josefa held a special Mexican fashion show in 1974 in Washington D.C. for all the ambassadors stationed there.

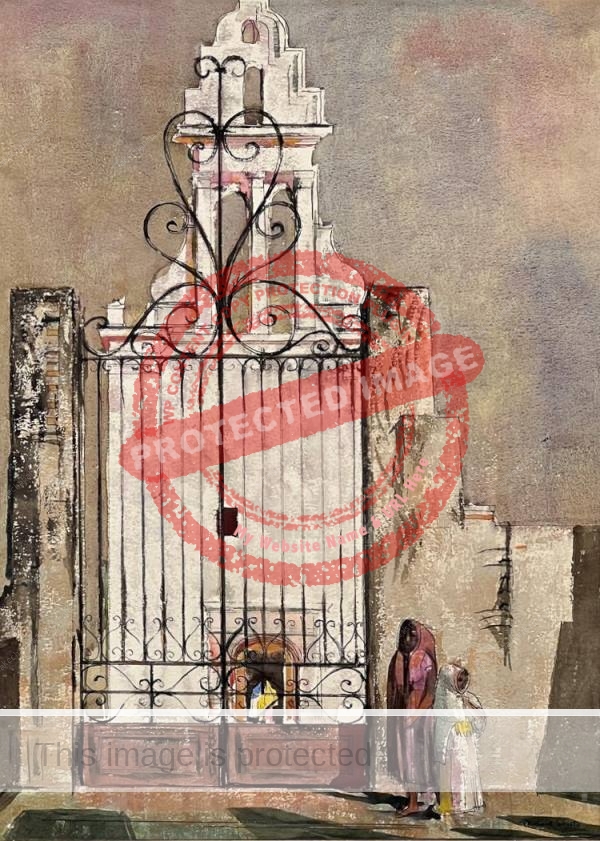

2004 exhibition of Mexican textiles and designs by Josefa

The extraordinary quality of Josefa’s designs and workmanship led to her work being the focus of a major exhibition in Mexico City at the Museo de la Indumentaria Luis Marquez Romay in 2004. A stunning display (250 designs in all) showcased Josefa’s manta kaftans in their distinctive Mexican textures and colors (turquoise, green, fuchsia, rose and yellow). Decorated with embroidered flowers, designs influenced by Mexico’s indigenous peoples, butterflies and geometric patterns, the exhibit was a kaleidoscope of color. Josefa had cemented her reputation as “an icon of national fashion design.”

Josefa’s designs were also included in 2009 in a second major Mexico City exhibition at the Mexico City Popular Art Museum (Museo de Arte Popular de la Ciudad de México). Curated by Mario Méndez, “México de autor, historia en color” juxtaposed Josefa’s “modern” designs alongside indigenous textile items from the Mapelli collection, emphasizing what they had in common and how one influenced the other. Josefa’s “Mexicanized” designs, celebrating bright colors, owed much to, and simultaneously increased the appeal of, indigenous textile patterns and clothing.

Josefa retired from designing clothing in the late 1980s.

While several earlier designers, such as Jim and Rita Tillet, had successfully established smaller operations and exported Mexican fashions, they had never succeeded in scaling up production to the levels reached by The Barefoot Eagle. Others, such as American Charmin Schlossman, who lived in Ajijic in the 1940s, took their creativity back home and established successful firms north of the border.

Mysterious early life

Relatively little is known for sure about her life story outside fashion. Adams described Josefa as Mexican born and residing in Tlaquepaque and the state of Oregon. According to a 2004 news piece, Josefa claimed to have been born in Chihuahua more than 80 years ago, while friends claimed she had arrived in Puerto Vallarta 30 years ago from the state of Oregon.

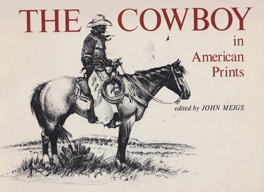

Label in Josefa blouse

According to the registration of her birth, Josefa Ibarra García was born on 12 April 1919 in Ciudad Sabinas Hidalgo in the state of Nuevo León. However, her birth was only registered in that city on 10 March 1928 when she was 9 years old! Her parents were Rafael Ibarra Valle (Rafael Ybarra-Valle in the USA) and Isidra García. The plaque on the grave of Josefa’s parents in a Fort Worth, Texas, cemetery, reads “Rafael Ybarra-Valle (1883-1968) / Isidra (1889-1981).” Both of Josefa’s parents were born in Mexico. The couple had at least four children: three girls and a boy. Even before the arrival of Josefa, the family had apparently been living on-and-off in Fort Worth, where their only son, Ray, was born in 1915.

According to Rubén Díaz, a friend of Josefa’s and now the editor of Mexico City-based Fashion News, Josefa returned to Mexico at age 18 (ie in about 1937) and traveled all over the country as a flight attendant with Mexicana de Aviación. After meeting and marrying Jim Heltzel (previously married to Eleanor Reed), the newly weds lived among the indigenous communities of various states in Mexico, including Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco, Veracruz and Guerrero, before settling in Puerto Vallarta.

During the 1980s and 1990s, The Barefoot Eagle’s prime years, Josefa lived at Lake Chapala. Her home (with one room devoted to a working studio) was designed by her good friend Jorge Wilmot, the famous potter. Wilmot added many personal touches to the home, located in El Limón, just west of San Juan Cosalá, including a special hand-made foot bath in the ensuite since Josefa, as her company name suggested, was accustomed to going barefoot most of the day.

Josefa’s success enabled her to travel more widely and she was particularly inspired by a trip to China. Unfortunately, in retirement, she experienced both health and financial problems. She came out of retirement to work for a while, offering designs for others to produce and market. Eventually, though, her declining health meant she could no longer focus on her passion. In a letter to a friend in May 2002, Josefa complained about three terrible months of ill health while waiting to have cataract surgery on the IMSS (Mexican Social Security) and admitted she was “getting fed up at waiting and not knowing a date.” Meanwhile, she wrote, she had accepted a job with

“a couple who will make up dresses from my designs…. I never thought I’d go back to those working days EVER – they were great days (while it lasted) but egods this is not the time to try and start up ANYTHING – it’s insane, that’s what it is but the peso isn’t worth a damn and with the bottom having fallen to NADA – things couldn’t be worse. (At least here in Chapala).”

Exhibition of Mexican textiles and designs by Josefa

In about 2006, as her health and finances continued to decline, Josefa sold her house and moved into a nursing home. When she abandoned her home, she left behind a decorated trunk full of personal photos, documents and design memorabilia. The new owner, a Canadian woman, kept the trunk in the house for years in homage to Josefa. When the house was eventually resold, she offered me the trunk for safe keeping to prevent it from being destroyed. If you can suggest a suitable permanent home for the trunk and contents, where it will be readily accessible to future researchers, please let me know.

Among Josefa’s effects in the trunk was a clearly-treasured, much folded and faded handwritten extract from Witter Bynner’s translation of Lao Tzu “The Way of Life.” It is unclear how well Josefa knew Bynner, who had a house in Chapala from 1940 to his death in 1968.

Before it move, hold it,

Before it go wrong, mould it,

Drain off water in winter before it freeze,

Before weeds grow, sow them to the breeze.

You can deal with what has not happened, can foresee

Harmful events and not allow them to be.

Though– as naturally as a seed becomes a tree of arm-wide girth-

There can rise a nine-tiered tower from a man’s handful of earth

Or here at your feet a thousand-mile journey have birth,

Quick action bruises,

Quick grasping loses.

Therefore a sane man’s care is not to exert

One move that can miss, one move that can hurt.

Most people who miss, after almost winning,

Should have ‘known the end from the beginning.’

A sane man is sane in knowing what things he can spare,

In not wishing what most people wish,

In not reaching for things that seem rare.

The cultured might call him heathenish,

This man of few words, because his one care

Is not to interfere but to let nature renew

The sense of direction men undo.

By 2008, Josefa was confined to a wheelchair while waiting for a hip replacement operation. A fashion fund raiser was held that year in Ajijic to help pay for her medical treatment.

Josefa Ibarra, artist, entrepreneur and mother of Mexican fashion, died in Ajijic on 30 June 2011. Her decision to develop designs incorporating folkloric motifs and her insistence on incorporating artisanal workmanship prodded Mexican fashion design into a direction still evident today.

Her continued influence on young Mexican designers was highlighted by an exhibit in Guadalajara in 2016. Examples of Josefa’s work formed the backdrop to an end of course display of work by young students graduating from UTEG (Universidad Tecnológica Empresarial de Guadalajara).

Several Josefa designs were chosen for inclusion in “El Arte de la Indumentaria y la Moda en México (1940-2015),” a Mexico City show held in 2016 at the Palacio de Cultura Banamex (Palacio de Iturbide) to commemorate 75 years of Mexican fashion design.

International interest in Josefa’s designs has also continued unabated. For example, her work was showcased north of the border in a December 2016 exhibit, “La Familia”, at Friends of Georgetown History (6206 Carleton Ave S) in Seattle, Washington. The show was of selected pieces from the collection of Allan Phillips, a grandson of Josefa’s sister, Olivia.

In 2017, Mexico was the featured country at the VII Congreso Bienal Latinoamericano de Moda in Cartagena, Colombia. An accompanying exhibit—“México Mágico”— took a retrospective look at the history of Mexico’s fashion industry, and how Josefa had set what had been only a nascent industry on the path to global success. The exhibit included contemporary work by students from the Universidad de Guadalajara that echoed the path laid down by Josefa.

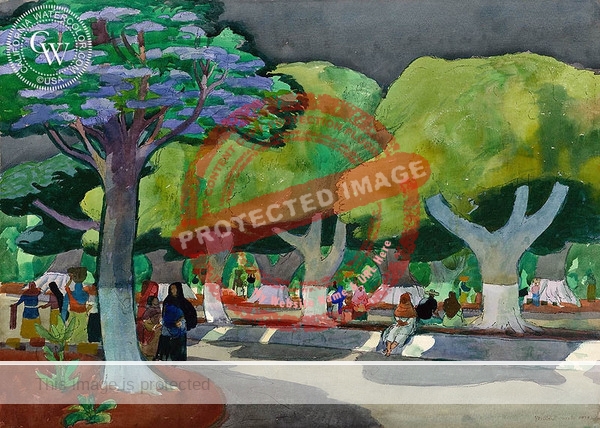

Josefa exhibit at Museo de Arte Popular de Yucatán, Merida. Photo: Marjorie Skouras.

In 2022, designer Marjorie Skouras sponsored an exhibit featuring her extensive collection of famed designers, including Josefa, at the Museo de Arte Popular de Yucatán in Mérida, Mexico. Josefa’s trunk and contents (see comments) were included. The trunk and contents are also part of the major show of Josefa’s career in fashion organized by Linda Mireles at the Costumes of the Americas Museum in Brownsville, Texas. This exhibit, which includes more than thirty dresses from Mireles’ private collection, opens 19 November 2024 and closes 16 May 2025.

Josefa’s legacy lives on. Her story has been shared with succeeding generations of fashion students in Mexico and she is justly referred to as “the mother of Mexican fashion” or as “Mexico’s Coco Chanel”. Students are taught that it is perfectly possible—indeed fashionably current and profitable—to bring elements of indigenous, local design to the global fashion scene.

Note: This is an expanded (and corrected) version of a post first published on 12 September 2018.

Acknowledgment

- My sincere thanks to Sherry Hudson for her assistance with compiling this profile, and to Marjorie Skouras and Linda Mireles for including Josefa memorabilia in exhibitions in Mérida and Brownsville, respectively. And heartfelt thanks, too, to Sra. Maricruz Ibarra (no relation to Josefa) for arranging to collect and store the trunk and contents following the house sale.

Sources

- Chris Adams. 2005. La Gran Josefa: Designer Emeritus International. First edition (2005) printed Guadalajara: Ocho Columnas, 2008; Xlibris edition has US copyright of 2010.

- Chris Adams. 2009. Up Your Sales in Any Economy: A Salesman’s Success Story @ Boston’s Historic Faneuil Hall Market Place. Xlibris Corporation.

- Lupita Aguilar. 2004. “‘Vuela’ de nuveo el Aguila Descalza.” Reforma (Mexico DF), 14 de Febrero de 2004.

- Artes Visuales ICL. 2009. “México de autor, historia en color” (Mario Mendez, Curator). Blog post. (8 April 2009) [15 Oct 2020]

- Ruben Diaz. 2010. “Josefa Ibarra,” in Adams, La Gran Josefa, 15.

- Sheryl Kornman. 1970. “Josefa: Designing for Living.” Guadalajara Reporter, 25 July 1970, 20.

- Lydia Lavín. 2016. “Magna Exposición El Arte de la Indumentaria y la Moda en México (1940-2015)”. Mexcostura #76 (July-Sep 2016), 53-55.

- Publimetro Colombia. 2017. “Vuelve Ixel Moda, el Congreso Bienal Latinoamericano de Moda.” 4 May 2017.

Comments, corrections or additional material are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.