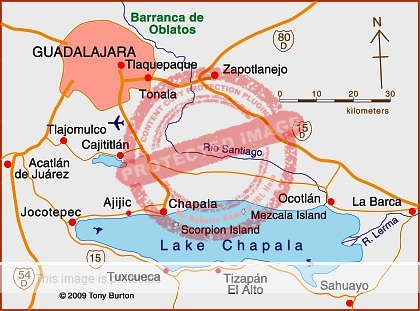

English-language newspapers at Lake Chapala may have a longer history than I thought. At the time I wrote about the Chapala Blade, I was fairly sure that that short-lived tabloid from the early 1960s was likely to be the earliest local periodical ever published at Lake Chapala. But, by an amazing coincidence, I recently stumbled across a one-line reference to an even earlier newspaper, The Chapala Profile.

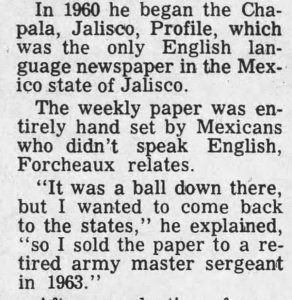

This was in a 1967 article about a Mr Joseph Forcheaux, then 38 years of age, who was combining a career as a minister with living a full-time carnival life. Forcheaux explained to the journalist interviewing him that, finding himself in Mexico, and wanting his ministry to reach a wider audience, “he founded, edited and published his own newspaper in Mexico…. In 1960 he began the Chapala, Jalisco, Profile, which was the only English language newspaper in the Mexico state of Jalisco.” The Chapala Profile was a weekly paper, “entirely hand set by Mexicans who didn’t speak English,” and that when he decided to leave Mexico and return to the U.S., he “sold the paper to a retired army master sergeant in 1963.”

Whether or not this is entirely accurate is unclear. I’ve been unable to locate any corroborating evidence, and a quick dive into Forcheaux’s life suggests that he often lived on the edge and may sometimes have stretched the truth.

Joseph George Forcheaux was born in 1929 in the Bronx, New York. After graduating from Haaran High School, he served with the U.S. Army in Japan and Korea (1948-1952). In Japan he helped found the Okinawa Boys Scouts organization, which had 1200 members by 1950. But in 1951 he was one of several men the draft board was reportedly trying to locate.

Only a few months after marrying Betty Jane Baumgardner (1931–2001) in April 1952, Forcheaux was arrested by Salinas police on an AWOL charge. He then began taking classes, under the G.I. Bill, at Pasasdena City College in California, where he majored in juvenile psychology.

In 1955 he was arrested and detained for driving a stolen car. In 1956 he started traveling with carnivals. But in 1957, Forcheaux turns up in Canada, where he was released from Toronto’s Don Jail in October with 37 cents and a seven-day notice to leave Canada. He appealed the decision on the grounds that he couldn’t “return to the United States, the land of his birth, having forfeited U.S. citizenship by joining the Canadian Army without U.S. permission.”

From 1958 to 1959, Forcheaux was apparently in Central America, before moving to Mexico in about 1960, where he started The Chapala Profile.

According to the 1967 article about him, Forcheaux returned to the Universal Church of God in Los Angeles every winter, to study theology in a small seminary of 11 brothers. He became a minister and started the House of Mercy, a rehabilitation center there for alcoholics and drug addicts.

Joseph Forcheaux died at age 81 on 10 December 2010. I think he might have had some great stories to share if only I’d heard about him sooner!

A brief history of English-language periodicals related to Lake Chapala

The two longest-running English-language periodicals reporting on events at Lake Chapala are The Guadalajara Reporter and El Ojo del Lago. The first issue of the weekly Guadalajara Reporter (formerly The Colony Reporter) left the presses in December 1963. Over the years a series of fine correspondents ensured good quality Lakeside content. They included Anita Lomax (1915–1987), a Texan who arrived in Ajijic in 1956 and started her column in 1964; Joe Weston; Beverly Hunt, who with her husband, Allyn, purchased the paper in 1975); Joan Frost; Ruth Netherton; Ruth Ross-Merrimer, Tim Hogan; Merry Barrickman; Teresa Kendrick; Jeanne Chaussee; and last—but certainly not least—the incomparable Dale Hoyt Palfrey, whose grandparents had lived at Lake Chapala in the early 1950s, and who moved to Ajijic (with her late husband Wayne) more than fifty years ago.

El Ojo del Lago, a free monthly, started in September 1984. Published by Richard Tingen, at the instigation of Cody and June Nay Summers, Diane Murray was its first editor. Tod Johnson was appointed editor-in-chief in 1988, when the publication organized its first annual El Ojo del Lago Awards Show. In 1992, award-winning writer Rosamaría Casas, recently retired from the Mexican Foreign Service, took over as editor; she was succeeded by Hollywood screenwriter Alejandro Grattan-Domínguez at the end of 1994.

Other relatively short-lived English-language publications over the years have included the Chapala Riviera Guide (1989–1993), edited by Jorge Romo, and the Lake Chapala Review (1999–2014), founded by Helyn Bercovitch, and edited by Darryl Tenenbaum and Judy King.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission. Learn more.

Sources

- The Globe (Worthington, Minnesota). 1967. “Joseph Forcheaux,” The Globe, 5 August 1967, 11.

- Guadalajara Reporter: 25 February 1967, 10; 25 November 1978, 17.

- Dale Hoyt Palfrey. 1994. “In the beginning were the words.” El Ojo del Lago, September 1994.

- The Kalamazoo Gazette: 12 Jan 1950, 32.

- The Miami Herald: 30 Sep 1951, 19; 12 Dec 1964, 6.

- The Californian: 23 Aug 1952, 2,

- Tallahassee Democrat: 27 Jan 1955, 2.

- The Standard (Toronto): 26 Oct 1957, 2.

Comments, corrections and additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

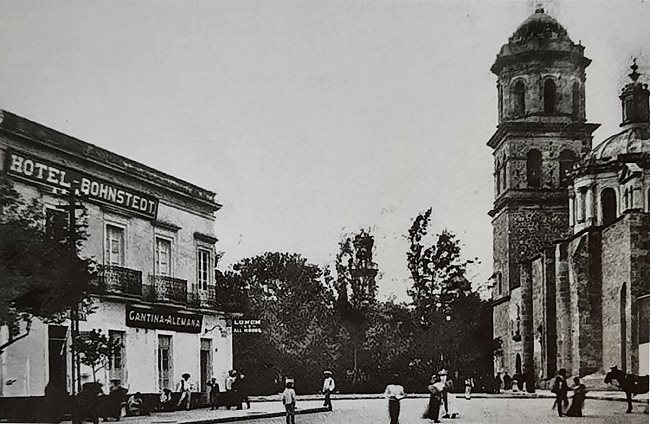

Its publication was timed to coincide with the designation of the City of Chapala as a “Ciudad Señorial e Insigne” (Stately and Distinguished City). The book has contributions by various writers and historians on a wide range of topics, from the early (precolonial) history and evangelization, to the events on Mezcala Island during the fight for independence, as well as details of the lives and contributions of certain key individuals to projects that established Chapala’s enduring appeal.

Its publication was timed to coincide with the designation of the City of Chapala as a “Ciudad Señorial e Insigne” (Stately and Distinguished City). The book has contributions by various writers and historians on a wide range of topics, from the early (precolonial) history and evangelization, to the events on Mezcala Island during the fight for independence, as well as details of the lives and contributions of certain key individuals to projects that established Chapala’s enduring appeal.

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.