As we saw in a previous post—Wilhelm Schiess described Chapala in 1899—Dr Schiess (1869-1929), a Swiss doctor, visited Chapala briefly in 1899 with his brother, Ernst, and later published a detailed account of their trip.

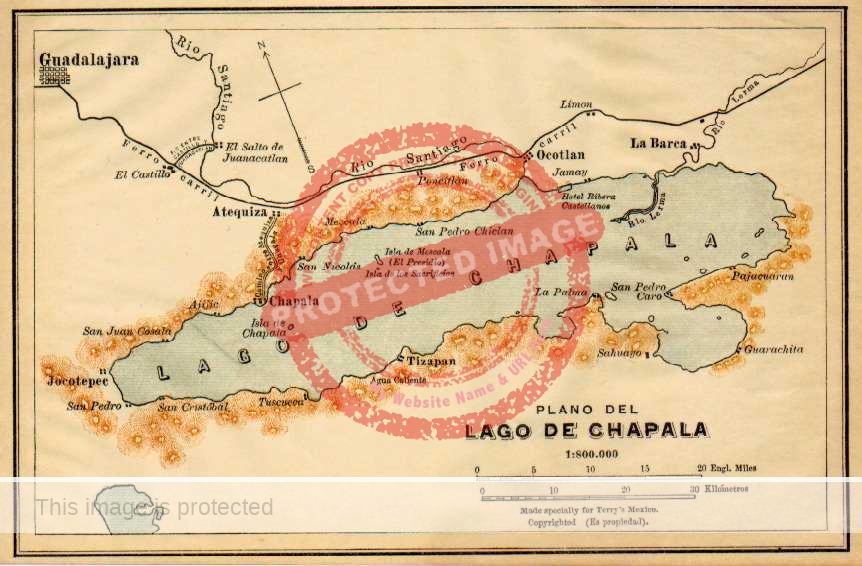

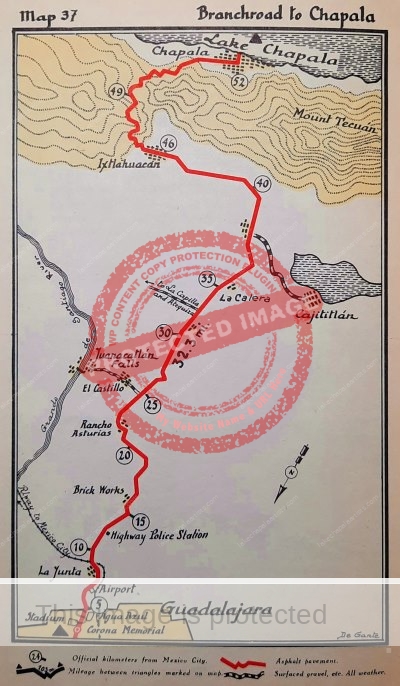

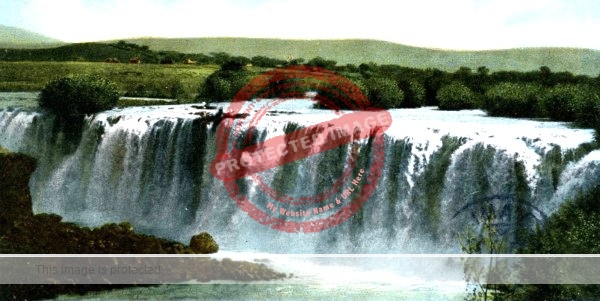

After a quick visit to Guadalajara, and seeing Juanacatlán Falls, the brothers had taken a special carriage from Atequiza to Chapala on Wednesday 6 December, where they had lunch at the Hotel Arzapalo, overlooking the lake. One bottle of red wine later, the brothers decided not to stay overnight at the hotel, but to take a boat to Ocotlán. This turned out be be far more of an adventure than they had ever imagined.

We could have stayed overnight in Chapala and taken the stagecoach back tomorrow. The steamboat arrives in Chapala only very irregularly and is mainly intended for transporting goods from the ranchos on the southern shore, so we could not rely on it…. Ernst therefore negotiated with two boatmen who agreed to take us to Ocotlán for 8 pesos [4 dollars]. The innkeeper warned us about the boat trip, as we would be completely dependent on the unpredictable whims of the wind, and an unreliable companion might leave us stranded for days along the way. But as if by a sign from heaven, a strong west wind suddenly rose, and the two sailors assured us that we would reach Ocotlán by 8.00pm.

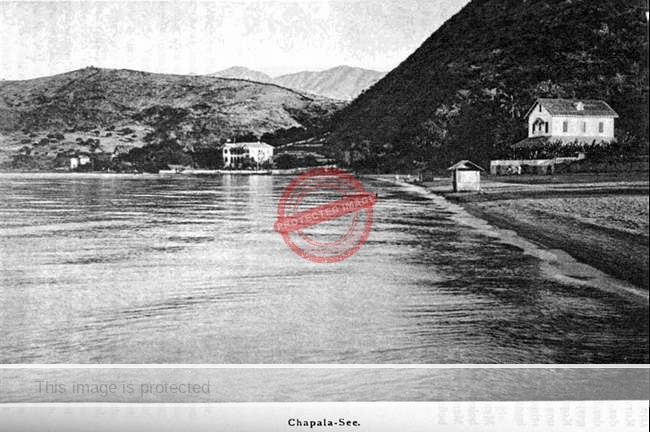

“At 3.40pm, we had loaded our luggage onto the boat and set sail. The innkeeper and the few remaining guests stood on the shore, waving their white handkerchiefs in farewell for a long time. Chapala is located near the western end of the lake, which is roughly the size of Lake Constance. From our wide, flat barge, we had a magnificent view of the mountain range enclosing the western side of the lake, at whose foot Chapala, with its charming villas, was beautifully situated. The sail was hoisted on the mast in the middle of the boat and secured to both sides. We had the wind coming directly from behind us, which could not have been more favorable, as these barges can only sail with the wind at their back. With the massive waves, our boat rocked dangerously in all directions, making it difficult to remain seated on the rickety little chairs that had been placed in the barge for us.

“The two mozos were barefoot, with their light manta trousers rolled up above mid-thigh. They steered the rudder and sang a few melancholic, monotonous Mexican tunes. The lake had a murky yellow color, but in the evening light, one could almost believe it was the clearest, most transparent water. Ernst and I grew quieter and quieter, a sense of unease creeping over us. We tossed our cigars overboard. I noticed my brother growing paler and paler, and I could feel the same happening to me. Cursed seasickness! We had crossed the ocean without trouble, even laughing at our suffering fellow passengers, and now—less than an hour on this lake—we had to admit that we, too, were not immune. We moved our chairs closer to the edge of the boat, and not in vain! Just as quickly as the sickness had come, it passed. The two mozos smiled slightly and advised us to smell a lemon—an infallible remedy for seasickness, they claimed. Half an hour later, Ernst’s cheeks were rosy again, and I felt as well as before.

“Unfortunately, the wind grew weaker, the waves subsided, and the lake became as smooth as a mirror. The sail was taken down. If we had already been making slow progress with a good wind, the heavy barge now barely moved at all.

The two Mexicans took up small, clumsy oars and began paddling. We stayed close to the northern shore, which was occasionally hilly, with scattered trees and a few cornfields. At 5.30pm, the sun set. In the west, long after darkness had fallen, a magnificent, grand glow remained, as if a colossal forest fire were raging in the distance. Gradually, even this fiery spectacle faded, leaving only the dark silhouettes of the mountains. Everything around us was pitch black. Aside from the monotonous, slow strokes of the oars, and the drowsy singing of the two sailors, there was no sound in this desolate expanse. The lake lay utterly calm and smooth, and we soon realized that reaching our destination that evening would be impossible.“We consulted with our two guides about whether it might be best to land and wait until morning. However, our companions were absolutely opposed to this idea. They began telling stories of robbers—each more terrifying than the last—and no treasure in the world could persuade them to dock at the shore. One of them claimed that his uncle had been murdered by native Indians just a few days ago, and even the captain of the steamboat had fallen victim to these people only a few weeks earlier. Listening to these tales, a deep sense of unease crept over us.

“The first quarter moon stood high in the sky, occasionally casting its pale light through the clouds onto our little boat. The lake was lightly rippled again, reflecting the silver moonlight. The mozos encouraged us to lie down on the floor of the barge and sleep. But could we trust these two strong young men? The innkeeper had recommended them, and besides, they couldn’t have gotten rid of us without the crime becoming known afterward. Moreover, Ernst still had his revolver…. So, we spread blankets over the damp wooden floor, stretched out, and covered ourselves as best we could. Our hard suitcases served as pillows. A sip of cognac, a piece of chocolate, a lump of sugar, and a small slice of sausage made up our frugal supper. Suddenly, Ernst, who was sleeping right next to me, jolted up in fright. He had dreamed that a mozo was leaning over him, trying to slit his throat. Instinctively, he stretched out a hand in defense—only to realize that the mozo was merely climbing over him to hoist the sail, with no sinister intentions. But just as the sail was raised, the wind died down again, forcing the Mexicans to keep stepping over us repeatedly. Finally, around 1.30am, even they grew tired. Their monotonous singing ceased, and we drifted into a small bay without landing. The two mozos lay down to sleep—one at the front of the boat, the other at the back.”

Source: Terry’s Mexico Handbook (1909)

The Schiess brothers survived the night, and woke up the following morning to find that:

Our barge lay motionless in the bay, not far from the shore. Heavy clouds covered the sky, except for a narrow blue-green strip on the eastern horizon. Then, the sun rose in an absolutely magnificent display. A vast fire spread across the entire mountain range and reflected in the lake, which took on a brilliant green hue. This dreamlike illumination lasted only a few minutes before vanishing completely. It began to rain, and for a brief moment, two massive rainbows arched across a large part of the lake in the west. Soon after, the sun disappeared behind thick clouds. The mountains darkened and were later partially shrouded in mist. We woke our two companions and continued our journey, staying close to the shore. Our only provisions for breakfast were a small tin of sardines…. With the help of the oars, we made slow progress. Whenever the lake’s shallow depth near the shore allowed, the boatmen used long poles to push off the lakebed, which helped us move forward more efficiently. Ernst played the harmonica, and the two mozos sang.

“Each time we passed an indigenous settlement, the mozos made a tremendous racket, shouting for eggs and tortillas. In front of the huts, we saw a few indigenous people, wearing nothing but cloaks made of maize straw, busy piling up corn. They paid no attention to our pleas or, at best, called back that they had nothing to spare. Several small villages, hidden among the greenery, came into view. Their huts were made entirely of maize straw. Here and there, cows grazed on the dry meadows. We caught up with a sailboat similar to ours and bought a few cigarettes from the boatmen. This boat, which we soon left far behind, had already been traveling from Chapala for three days, so we had to consider ourselves lucky to have come so far in such a short time.

“At 10 o’clock, we spotted two miserable straw huts on land and an old woman hurrying back and forth between them. Summoning their courage, the mozos asked Ernst to keep the revolver ready, then—miraculously—went ashore. They returned beaming with warm tortillas made from red maize and a few fresh eggs. We devoured this dry breakfast with great appetite, though it had been slightly dampened by the rain. It was pouring in torrents, and water streamed from our hats as if from gutters. Trees stood deep in the water along the shore, their crowns dipping far into the lake. The southern shore was no longer visible—thick veils of mist shrouded the mountains.

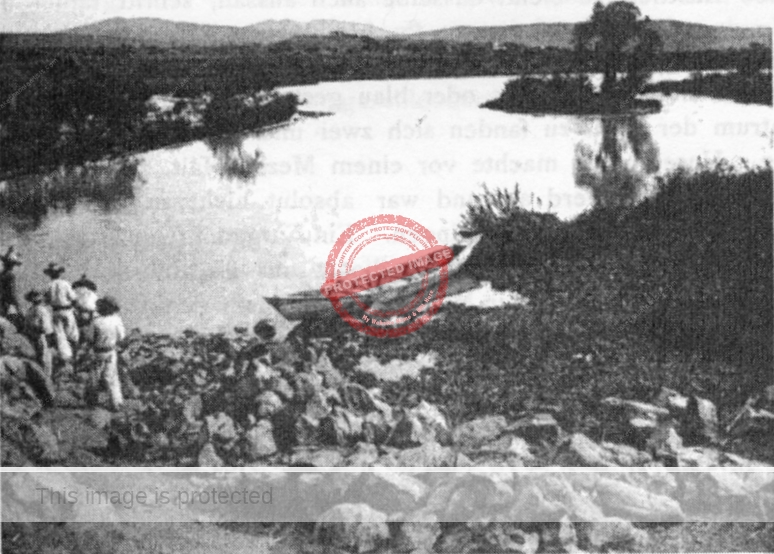

“Around 11.30am, we finally arrived in the bay of Ocotlán, which is bordered to the east by a rocky mountain and to the west by some hills covered with cornfields. It was too late to catch the train to Zamora that day, but that hardly mattered, as we first needed to dry off. The rain had gradually seeped through the wool blankets, leaving us completely soaked. In the bay, the lake gradually took on a lagoon-like appearance. A vast number of ducks could be seen here. Passing through trees and reeds, we reached the mouth of the Río Grande.”

They finally made it to Ocotlán at around 1.30pm:

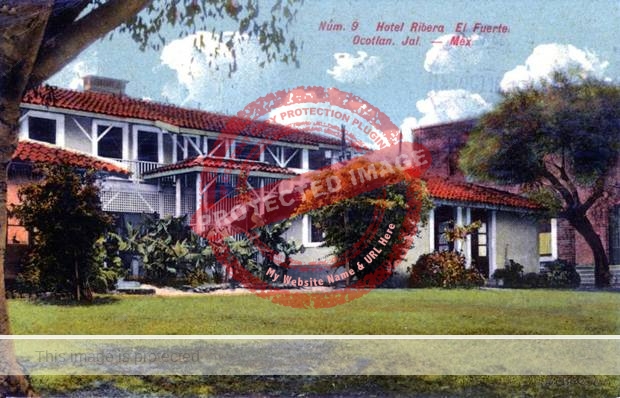

“Here, in one of the canals, lay the steamboat, which was built similarly to the Mississippi riverboats, with a colossal paddle wheel at the back, although it only had about half of its original paddles left. We made some purchases in the plaza, including candles to have festive lighting in the evening. At the Mexican hotel, where there was only one other guest besides us, we immediately sent the landlady to the kitchen, and soon we were served something warm to eat.”

After a meal and a good night’s sleep, they continued on their way:

Friday, December 8th. At 6.45am, the thermometer showed +12°C, and it felt quite warm to us now that we were in completely dry clothes again…. We climbed up the church tower; from a platform, under the bells, and surrounded by the various domes of the church, we had a wide, open view of the entire landscape. To the south, we could see a shining strip, the Chapala Lake, and beyond it, the beautifully shaped mountains. At our feet, the Rio Grande meandered with its green banks through the plain, gradually dissolving into numerous lagoons. Before us lay the plaza planted with orange trees, where a vast number of people were currently gathered. Beyond the flat rooftops of the houses, numerous hills could be seen, only sparsely wooded…. After lunch, we took the tram to the station, about 10 minutes away. . . .

“At around 1 o’clock, it was +21°C at the station. The train took us through a flat area with many lagoons, a splendid hunting ground for duck hunters. Here and there, we could see green fields. In La Barca, where there was again a tram connection to the town, we had a few minutes’ stop. What a scene it was at the station! Mexicans and their wives, along with a large number of children, walked from one train window to another, carrying baskets and trays, hawking their goods. You could buy sandwiches with half chickens, radishes, oranges, beer, goat cheese, tortillas—all at a cheap price. Mexicans are masters at quickly devouring massive bites, and the baskets emptied out rapidly. Blind and lame beggars, singing and playing harps, were led by their wives from one compartment to another. The heart-wrenching and ear-piercing songs had their effect, as copper coins were often thrown from the windows.”

Sources

- Wilhelm Schiess. 1902. Quer durch Mexiko vom Atlantischen zum Stillen Ocean. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”

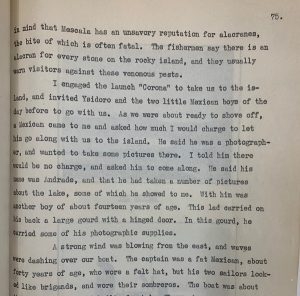

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).