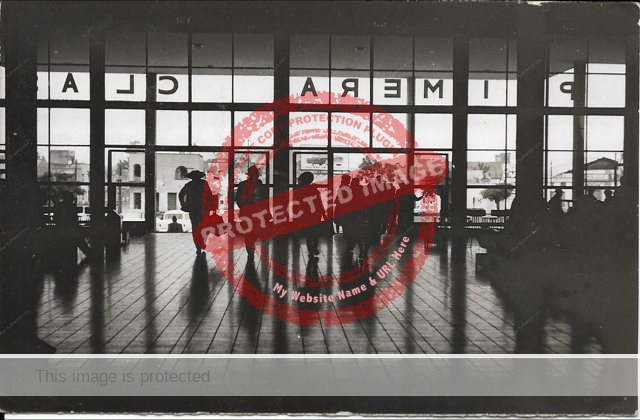

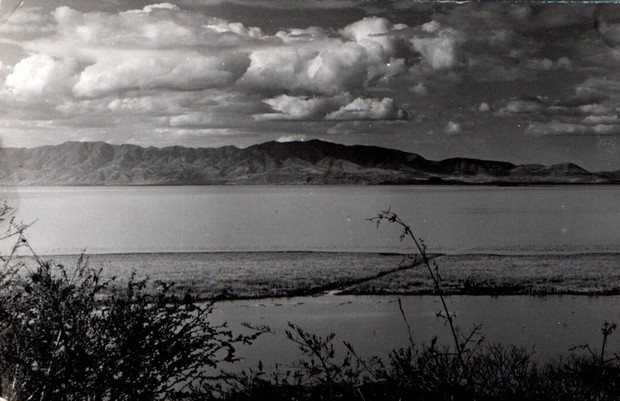

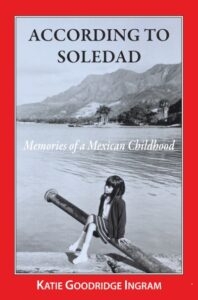

This beautiful postcard of Lake Chapala sold recently on eBay. The card had been mailed to California, most likely in early 1957, as the lake was recovering from its worst-ever drought. I’m familiar with more than 1000 postcard images of Lake Chapala but this photograph was new to me. It turns out, from the message on the back, that it was taken by the sender, someone named Lola, then studying photography at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende.

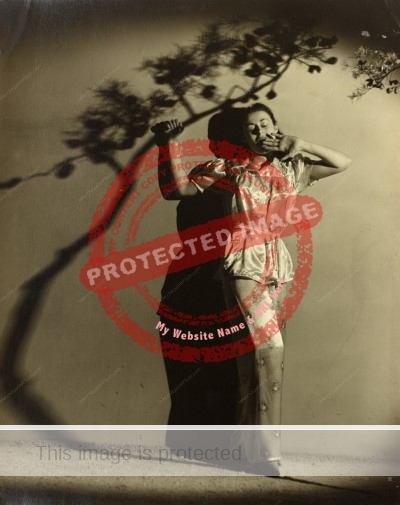

Lola Beall Graham. c 1956. Lake Chapala. Photograph (b/w) privately published as a postcard.

Though I initially imagined someone in their twenties or thirties enjoying a year or two away from home in a foreign country, it turns out that I couldn’t have been more wrong.

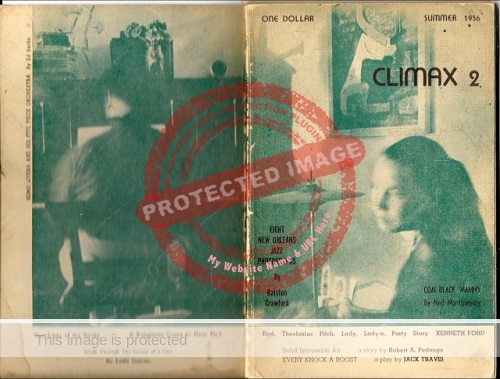

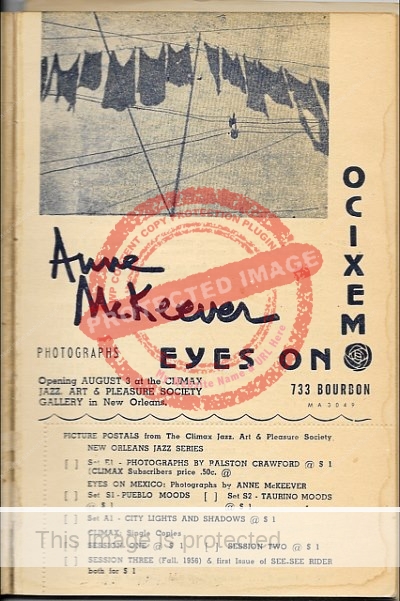

A little detective work was required to identify Lola. Her message included the intriguing line, “Did you see my picture in Nov. Popular Photography? Page 71?” Fortunately, I was able to locate that issue online and find a photograph credited to Lola Beall Graham, a name which generated more hits than I expected in a popular search engine.

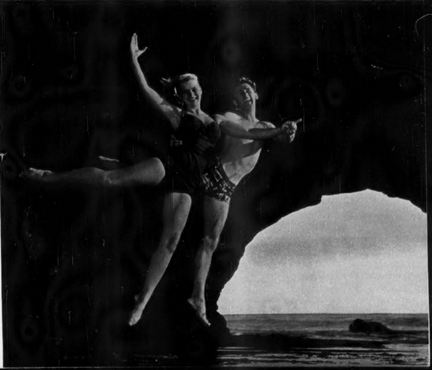

Lola Beall Graham. c 1956. Photograph (original in color) published in Popular Photography, Vol 39 #5 (November 1956), p 71. Rolleiflex, Ektachrome, blue flash, 1/250, f/8.

The photograph in Popular Photography was taken at Arch Rock Beach in Santa Cruz, California. The short text accompanying it explained that Lola was determined to catch the two figures (her daughter and son-in-law) framed against the cave entrance, “but used up all her flashbulbs before she caught the leap from the right angle.”

At the time she was studying and traveling in Mexico, Lola Beall Graham was a married woman in her fifties, a retired teacher, widely published poet, and mother of five children. Her traveling companion in Mexico was her son-in-law Jack, who was taking Spanish classes at the Instituto.

Lola’s photograph of Lake Chapala marked an inflection point in her distinguished literary and artistic career, the start of a fascination with photography which led to many prize-winning images and a semi-professional career selling photographs to magazines in the U.S. and overseas.

Lola Amanda Beall Graham was born in Bremen, Georgia on 12 November 1898 and died on 14 Feb 1996 in Santa Cruz, California. She married Jackson John Graham (1893-1968) on 3 August 1917. They settled in Scotts Valley, California, in about 1928, where Jackson ran an extensive ranch. (One of their sons developed part of the acreage into Spring Lake Mobile Home Park in the 1970s.)

She was the author of several children’s stories, song lyrics, and scripts for puppet shows, as well as a wide range of poems, drawing on her Methodist beliefs, with titles such as “When God Intercedes,” “My Magic Sea,” “My Dreamland.” Her poems were included in many anthologies and newspapers, as well as in Psychology, Adult Bible Class monthly, American Author, and poetry journals.

Lola was a long-standing member of the Santa Cruz Chapter of the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, and her photographs illustrated an anthology of Santa Cruz Chaparral Poets, published in 1973.

Her poem “Come Spring” won a Writers Digest national poetry contest in 1963, and “For Every Monkey Child” won two national poetry prizes in 1981. Lola published Recycling Center, a collection of her poems, in 1988.

Lola Beall Graham started taking photography seriously in the early 1950s after joining the Santa Cruz Camera Club. Her work, both black and white prints and color slides, regularly won prizes in multiple categories in local competitions, and she was soon notching up regional prizes too. The San Francisco Examiner published her photo of an owl waking up—“Wise Old Owl”—in 1959, and awarded her a prize for “Corn Factory” (a picture of metates taken in San Miguel de Allende) two years later.

Following the death of her husband in 1968, Lola traveled to Africa for three months. She also undertook extensive photographic trips with her Rolleiflex to Alaska, Canada, the Galapagos Islands and the Far East, gaining a reputation as an excellent wildlife photographer. She gave numerous slide talks on photography and her travels, and held photographic exhibitions at Spring Lakes Clubhouse in Scotts Valley in 1974, and at Aptos Public Library in 1976.

Lola’s Lake Chapala postcard was mailed to Paul F. Covel, a friend in Oakland. Her typewritten message referred to a failed attempt to see him a few months earlier and explained that she “was hoping to get some stuffed birds or little animals for pictures!”

Paul Frederick Covel (1908–1990) was a renowned California naturalist, the first municipal naturalist anywhere in the U.S., and a long-time member and chairperson of the conservation committee of Golden Gate Audubon Society in Berkeley. He worked for the Oakland Museum and at the Lake Merritt Wildlife Refuge, designed the Rotary Nature Center (1953) and authored several books including People Are for the Birds (1978) and Beacons along a Naturalist’s Trail: California Naturalists and Innovators (1988).

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission. Learn more.

Sources

- Oakland Tribune: 28 Feb 1932.

- Salt Lake Tribune: 11 Dec 1927, 53.

- San Francisco Examiner: 20 Dec 1959, 70; 27 Jan 1961, 52.

- Santa Cruz Sentinel: 8 Oct 1933, 8; 8 Mar 1935, 6; 18 May 1938, 2; 11 Nov 1938, 2; 23 Sep 1954, 2; 27 Mar 1955, 3; 23 Sep 1956, 2; 7 Oct 1956; 20 Mar 1963, 3; 6 Jun 1971, 14; 24 Jul 1974, 11; 24 Jan 1975, 8; 22 Mar 1978, 14; 11 Jan 1981, 24; 7 Sep 1986, 108; 16 Feb 1996, 8.

- St Joseph News-Press: 24 May 1936, 24; 23 Aug 1936, 20.

Comments, corrections and additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

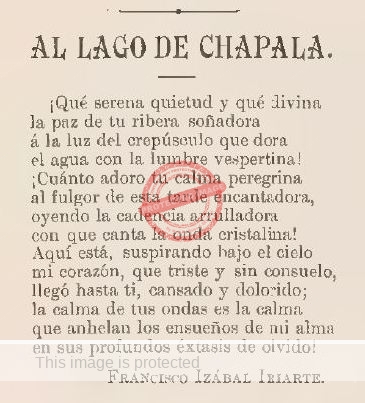

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

In “Lake Chapala,” Mary Ashley Townsend, looking across the waters of the lake from her stately residence, Villa Montecarlo, indulged her imagination and poetic talents.

In “Lake Chapala,” Mary Ashley Townsend, looking across the waters of the lake from her stately residence, Villa Montecarlo, indulged her imagination and poetic talents.

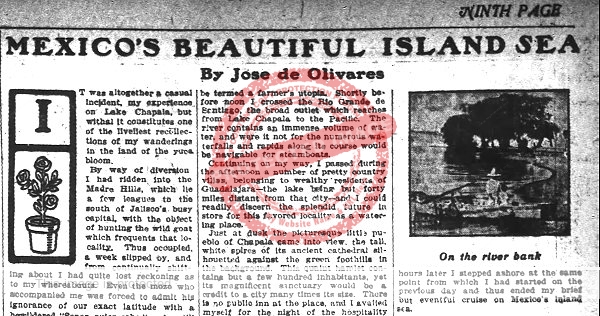

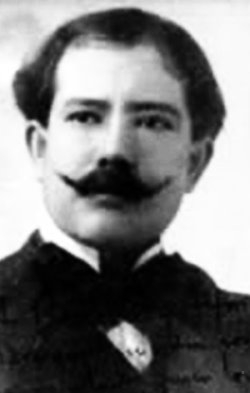

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.