One of the more interesting “on the ground” nineteenth century reports related to Lake Chapala is that written by Dr. Crescencio García in 1868. García was interested in all aspects of natural science and keen to share his experiences and findings with the wider world.

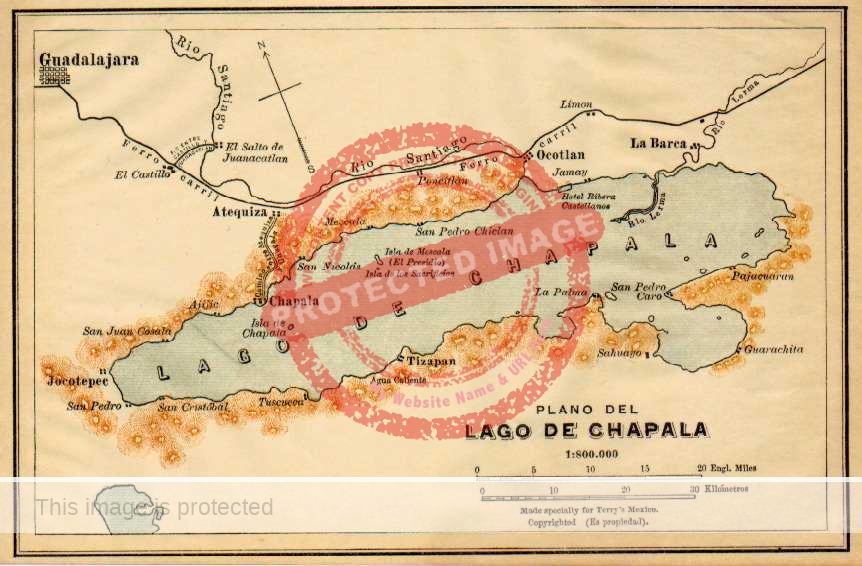

Lake Chapala in 1868

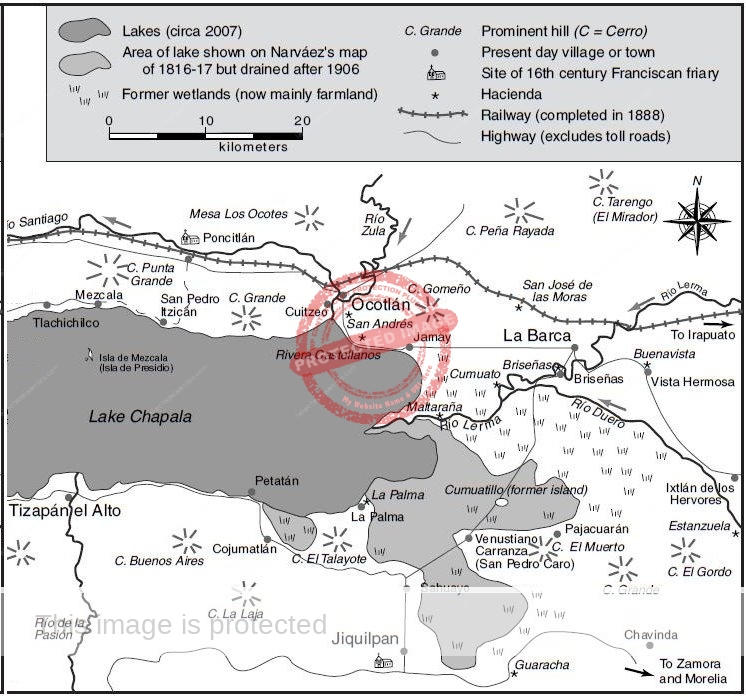

García’s wide-ranging eye-witness account of Lake Chapala was dated 30 May 1868. It was based on a trip taken a month earlier, in which he crossed the lake from Tizapán [el Alto] to Chapala to visit his father’s grave in that town.

Here is a summary of some of the many topics mentioned by García.

1. Yachts and Steamships

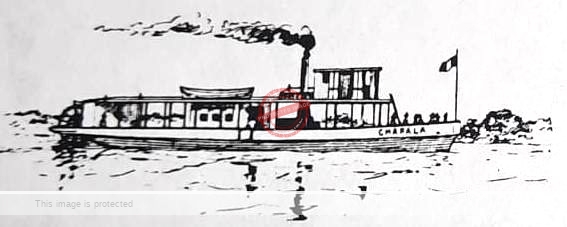

When García arrived in Chapala, he found a crew of men working to reassemble the Libertad. The Libertad, the first steamship on the lake, had been manufactured in San Fransisco by the Neptune Iron Works (owned by Duncan Cameron) and then brought in pieces overland from the port of San Blas to the lake. García described the ship, and its 50,000 rivets, and also named two other people besides Cameron: ‘Mister Broche’ and ‘Sr. Méndez de León.’

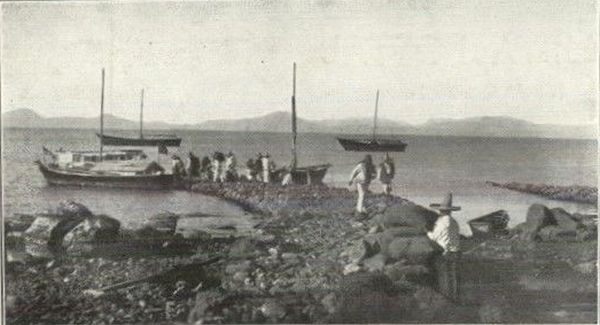

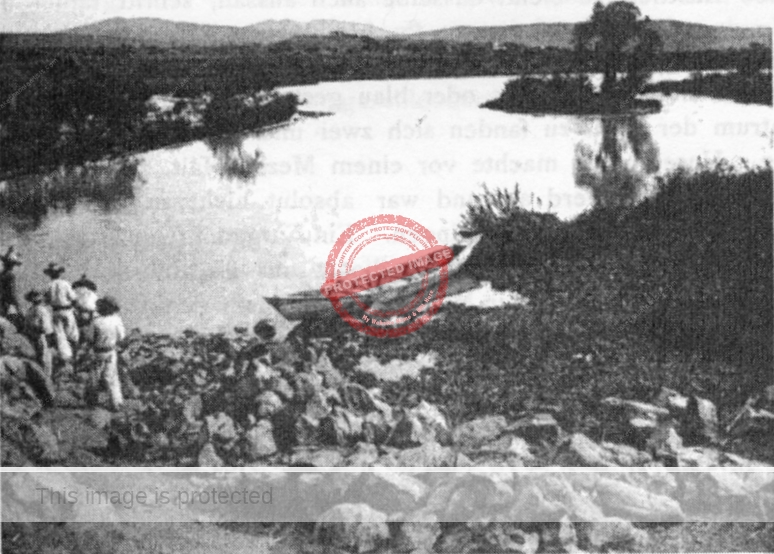

The Libertad (image from a stereoscopic pair, photographer and date unknown)

‘Mister Broche’ took García out on the lake aboard a sailboat, with a mainsail, foresail and rudder, “built by the Americans who were assembling the steamship.” This is the earliest recorded description of a pleasure yacht on the lake, preceding the custom-made German yacht imported by Septimus Crowe by more than twenty years.

‘Mister Broche’ is believed to be William (Guillermo) Brotchie, who was born on 31 March 1821 in Kirkwall, Orkney, Scotland. How and why Brotchie came to be in Guadalajara is unknown, but he married Guadalajara-born Juana Gómez Jayme in the city in about 1844. One of his grandsons—Luis Páez Brotchie (1893-1968)—was a noted Jalisco writer and historian.

‘Sr. Méndez de León’ was the mechanical engineer in charge of getting the Libertad ready for its inaugural launch. There is newspaper account of a “Jaime Méndez de León” who was skippering the Libertad in 1870 when a young boy fell overboard and drowned. However, I suspect the news report was mistaken about his first name, and believe this individual was almost certainly Jacobo Méndez de León (1845-1899), who was born in the Netherlands, and whose arrival in Mexico in the winter of 1867-68 closely coincided with that of Duncan Cameron. Jacobo married Apolonia Jiménez Hernández in La Barca in May 1870. He later imported European watches, ornaments and scientific instruments, served on the scientific commission for the 1878 Exposition in León, Guanajuato, wrote about education, and taught English in several states.

- For more about steamships, see “The golden age of steamships and other motorized vessels on Lake Chapala.”

2. Rescuing a kidnap victim

While on the yacht with Brotchie, García saw a man force a woman into a canoa and attempt to row away from his pursuers. The yacht was able to force the canoa back to shore where the man was detained. Unfortunately, the girl’s brother grabbed a gun from one of the soldiers. In trying to shoot the abductor he accidentally killed the local mayor. (Note: I have been unable to corroborate this claim.)

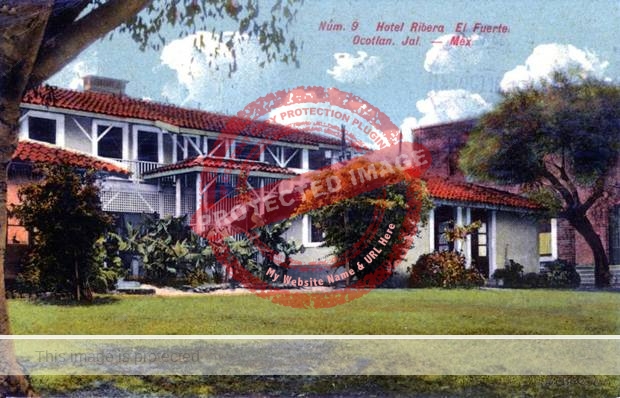

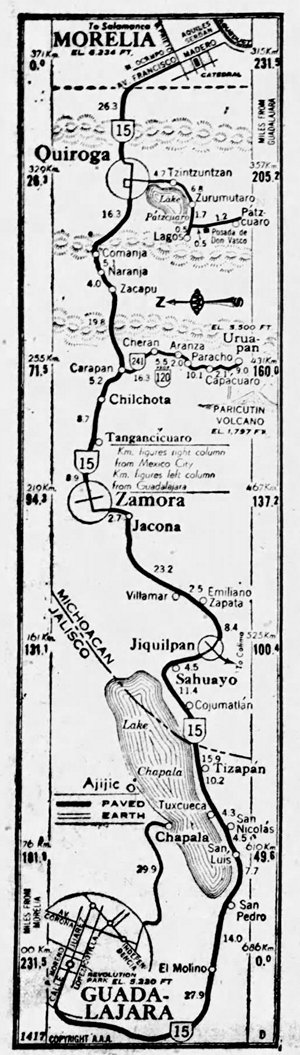

3. The need for a railway line to La Palma

García foresaw that the success of a steamship service would depend in part on the ease with which goods could be transported to and from the small port of La Palma on the Michoacán side of the lake. He argued the need for a railroad to be built linking Morelia to La Palma, and suggested that in the interim a regular stagecoach service should be established on that route.

Jetty at La Palma, c. 1901. Detail from a postcard published by Buedingen Art Publishing Co.

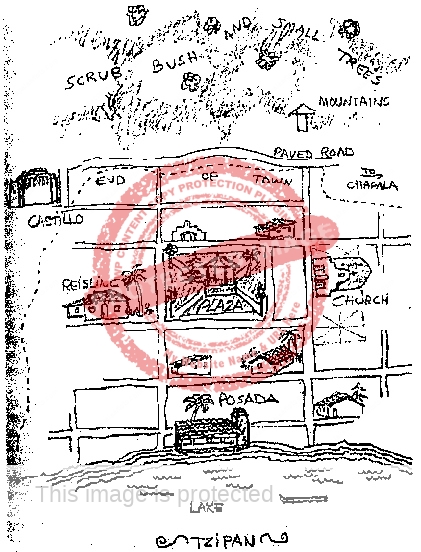

4. The town of Chapala

García highlighted the delightful location of Chapala, at the foot of a small hill, and noted its therapeutic hot springs “where many sick people recover their health.” He also commented on the many plants and fruits of the area, including coconut palms, mamey, papaya, bananas, plantains and coffee, and the “prodigious fertility” of the land near Tizapán, where sweet potatoes weighing thirty pounds, potatoes weighing eight pounds, and onions with a diameter of seven inches, had been harvested.

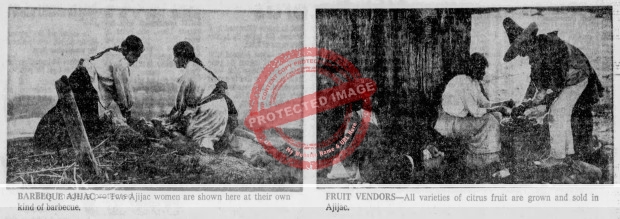

5. Ajijic

García reported that several silver mines were being exploited in Ajijic. Silver had been discovered there in 1856 by don Antonio Vallín, a Chapala resident, whose interests had been acquired by some wealthy residents of Guadalajara. They hired mining engineer Ramón Gómez from Hostotipaquillo to manage operations, but plans were interrupted by an uprising in 1858.

6. Natural bitumen

García described in detail the deposits of chicle negro or bitumen, and the location of underwater thermal springs at the bottom of the lagoon off “la punta de Columba,” which forced bitumen to the surface. He recalled how, a few years earlier, he and his father had collected one clump, “which weighed more than two arrobas [about 10 kg] and was very useful to my father for caulking his boat.” García had spoken with Duncan Cameron about constructing a thick pipe of laminated iron, about ten yards long, joined with rivets, so that this bitumen could be easily mined.

7. Storms, Plants, Birds, Fish, Fishing

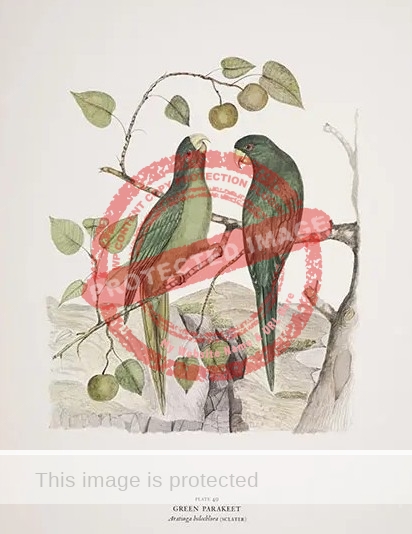

García included a poetic description of culebras (snakes), the local name for water spouts which he rightly called “one of the magnificent spectacles that can be observed in the lagoon,” and shared lists of the plants, birds, fish species and varied fishing methods employed by lake fishermen.

8. Mezcala Island

And, like many other writers before and since, García added a useful summary account of the historical importance of Mezcala Island at the start of the nineteenth century, during Mexico’s struggles to attain Independence.

Who was Dr. Crescencio García?

Dr. Crescencio García Abarca was born in Guadalajara on 19 April 1819 (date on his baptismal record). His father, Ramón García (ca. 1800-1862) owned a small business in the city. After studying in Guadalajara, Crescencio worked as a doctor in Jiquilpan and Cotija; in 1873 he was appointed prefecto (administrative head) of the district of Jiquilpan.

García was described as a ‘naturalist’ when he was appointed in March 1878 to a three-person scientific commission to explore southern Michoacán for minerals and natural resources, alongside lithographer and geological engineer Carlos Nice and an unnamed mining engineer.

In 1884, Dr Crescencio García arrived in Morelia with a collection of items, which included several rare species of plants with medicinal properties. This “rich collection of medicinal plants” was exhibited at the World Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans, which opened in December that year.

In 1891, García reported on his findings in relation to the treatment methods for tuberculosis advanced by Dr. Robert Koch. He concluded that Koch’s methods may work in incipient cases, and ameliorate the disease’s impacts in later stages, but that the root of an evergreen plant locally called Iololique (named by García Ipomoea semper viridens) was at least equally effective. Its curative properties had been revealed to him by an indigenous family living to the south of Lake Chapala.

García wrote numerous papers and collaborated with several periodicals in Mexico City and elsewhere. In addition to works related to medicine, traditional remedies, and the geography and history of his local area (such as Noticias históricas, geográficas y estadísticas del distrito de Xiquilpan, 1873), he also published two local Cotija publications: El Pájaro Volando (1883) and El Soldado de la Paz (1889).

García remained active into his seventies. He married Antonia Sandoval in Cotija on 5 March 1893 and died there a year and a day later on 6 March 1894.

Sources:

- Crescencio García. 1868. “Impresiones de un Viaje a Chápala.” El Constitucionalista, Morelia, 29 de junio de 1868. Reprinted in Alvaro Ochoa Serrano (ed). 1996. Medicina, historia y paisaje. Colegio de Michoacán / Morevallado Editores, pp 225-240.

- La Gacetilla: 8 Mar 1878, 1.

- La Voz de México: 7 Oct 1884, 3; 18 Jul 1891, 3.

- The Two Republics: 18 Nov 1884, 4.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via email or comments feature.

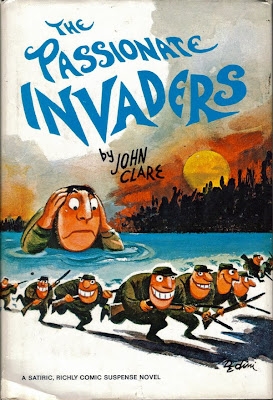

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.

Lumholtz made six separate trips to Mexico, with the express purpose of studying indigenous people and their beliefs and customs. This approach was in stark contrast to that adopted by previous travelers, who had tended to regard the contributions of native Indians to the overall picture of life and work in Mexico as relatively insignificant.