The iconic landmark right in the heart of Chapala commonly known as Casa Braniff (Paseo Ramón Corona 18) was originally built by influential Guadalajara lawyer and historian Luis Pérez Verdía. The building has significant historical and cultural connections.

Construction of this magnificent edifice began in 1904 on the site of Chapala’s sixteenth century friary, close to the parish church. By the end of the nineteenth century, the friary buildings had fallen into disrepair and were used by the Hotel Arzapalo as stables for the teams of horses that pulled their stagecoaches.

San Francisco Church and Casa Braniff, c. 1925. Photo: Romero (?). Publisher: S. Altamirano.

To design his new home, Pérez Verdía commissioned British architect George Edward King, who had previously built Villa Tlalocan for the British consul, Lionel Carden, and who, with his son, had offices in several Mexican cities, including Guadalajara. Expected to cost $30,000, the “fine residence” was to be “a modern structure in every way.” By June, with work well underway, the estimated cost of the house had already risen to $40,000. Contrary to later conjecture, the bricks for Pérez Verdía’s house were not imported from Europe; they came from King’s own brickyards, located alongside the Central Mexican Railway on the southern outskirts of Guadalajara.

When the house was completed early in 1905, the state government agreed to exempt the property from all municipal and state taxes for a period of ten years.

Two years later, in March 1907, Pérez Verdía offered José Yves Limantour, the federal finance minister, the use of his house over the upcoming holidays. Apparently, the letter only reached Limantour after he had already arrived in Chapala. Shortly afterwards, Pérez Verdía sold the house, complete with its furnishings, for $57,000 to Alberto Braniff, a wealthy Mexico City businessman, who bought it as a gift for his widowed mother.

The quixotic design of the house, now the Restaurant Cazadores, was perfectly encapsulated in words by American poet Witter Bynner, who first saw it in 1923 while in Chapala with D. H. Lawrence: “We came by a pretentious Victorian brick villa, in the convulsive style of architecture—bay windows, turrets, cupolas, stained-glass windows.”

Casa Braniff (with church behind). Photo: Tony Burton, 2007.

Who was Luis Pérez Verdía?

Pérez Verdía, born in 1857, grew up in the intellectual milieu of Guadalajara and was a member of the Ateneo Jalisciense, Jalisco’s leading artistic-scientific society. The society, active at the very start of the twentieth century, brought together a host of distinguished writers, artists and musicians, including photographer José María Lupercio, violinist and painter Félix Bernardelli, and artist and author Gerardo Murillo (Dr. Atl).

In the 1880s, Pérez Verdía was the lawyer in Guadalajara who represented Ferrocarril Central Mexicano (Mexican Central Railway) as it acquired land and overcame all obstacles to build its spur line, completed in 1888, connecting the city to existing tracks at Irapuato.

Pérez Verdía was the official representative for Jalisco at the 11th International Americanistas Congress in Mexico City in 1895, an event also attended by Cora Townsend and her mother, Mary Ashley Townsend (Cora bought Villa Montecarlo as her mother’s Christmas present that year!), British consul Lionel Carden, who had already begun building Villa Tlalocan, and anthropologist Frederick Starr.

Pérez Verdía was involved in various development projects in Chapala. In 1896, he reportedly bought Isla de Alacranes (Scorpion Island) from the federal government for “the nominal sum of twenty-one dollars.” He planned to pay a bounty to rid the island of scorpions and “convert the Isla into a pleasure resort like Coney island.” About five years later, he sold the island to Ernesto Paulsen, who intended to build a “general sporting resort” there. The island, a site revered by the indigenous Huichol people, is partially protected today.

Pérez Verdía was also a member of the group of powerful and well-connected individuals that formed the Jalisco development company in 1902, with grandiose plans to build an electric railroad from Guadalajara to Chapala, hotels, supply electric light to all settlements from Jocotepec to Chapala, and finance large scale irrigation works, and install a public potable water system in all towns.

A similarly powerful group, including Pérez Verdía, founded the Chapala Yacht Club in 1904, though it would take another six years before it finally realized its goal of constructing a lengthy pier with boathouse and clubhouse.

In 1905, the Chapala council empowered Luis Pérez Verdia to represent them in their efforts to get help from the Jalisco State government to combat the proliferation of lirio (water hyacinth) that had invaded the harbor during the rainy season. Documents in Chapala’s archives show that a contract was drawn up with Jesús Cuevas for daily cleaning of the beach, with all lirio to be removed by boat for disposal elsewhere.

Besides working as a lawyer, and later as a magistrate and state congressman, Pérez Verdía founded Jalisco’s college for teachers (Escuela Normal). He took up a diplomatic post as Minister of Mexico in 1913 in Guatemala, where he died the following year.

Pérez Verdía’s three-volume Historia Particular del Estado de Jalisco (1910) was an astonishing labor of love which remained an important source of state history for decades, prior to being superseded by the monumental four-volume multi-author Historia de Jalisco in 1982.

Pérez Verdía’s many other published works include Apuntes Históricos de la Guerra de Independencia en Jalisco (1886); Compendio de la Historia de México (1892); Biografía del Sr. Don Prisciliano Sánchez (1881) and Estudio biográfico del Sr. Lic. D. Jesús López Portillo (1908).

Pérez Verdía claimed custody of his granddaughter

Luis Pérez Verdía married Trinidad Pérez González Rubio in Guadalajara in 1877. Their daughter, Aurora Pérez Verdía, fell in love with José Ignacio Arzapalo Pacheco, the son of businessman and hotelier Ignacio Arzapalo (who had opened his eponymous hotel in Chapala in 1898) and his second wife, María Pacheco. Aurora and José married in 1900, and their only child—María Aurora—was born the following year. Tragically, Aurora died shortly after giving birth. A few years later, in 1904, the little girl also lost her father. She was then cared for by her paternal grandparents.

But tragedy struck again. Her grandfather, Ignacio Arzapalo Sr., died in 1909, only a year after he had opened his second elegant hotel in Chapala, the Hotel Palmera. According to Arzapalo’s will, both hotels plus his life insurance and some property in central Guadalajara were left to María Aurora (then aged 7), with Lic. Enrique Pazos appointed as María Aurora’s guardian to manage her affairs until she came of age. This inheritance was worth at least US$300,000 at the time (equivalent to $7.5 million today); for whatever motives, Luis Pérez Verdía, her maternal grandfather, immediately challenged the arrangement.

When the ever-impatient Pérez Verdía decided that his legal challenge was proceeding too slowly, he took matters into his own hands. He kidnapped María Aurora in broad daylight from her nurse in a public park in Guadalajara, and contested Pazos’ right to be her guardian and administer her share of the estate. Not surprisingly, this sequence of events led to sensationalist press headlines.

One version, “Wealthy Orphan Vanishes,” claimed that orphan Aurora Arzapalo, heiress to millions, had been kidnapped and that the police had arrested several suspects among her relatives, “all of whom are wealthy but would fall heir to some of the Arzapalo millions if the child were out of the way.”

The drawn-out legal case, which caused a scandalous rift between two of Guadalajara’s most distinguished families, who had at least two direct ties by marriage, eventually wound up in the Supreme Court, where Pérez Verdía finally won. But this success was short-lived. While serving as Mexican ambassador in Guatemala, Pérez Verdía died there in 1914. María Aurora, still barely a teenager, then lived in Chapala with her paternal grandmother, María Pacheco.

Sources

Note

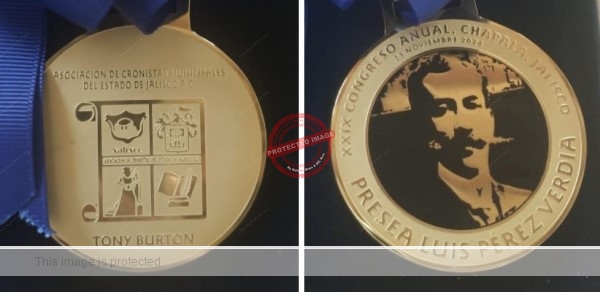

I am proud to announce that the Asociación de Cronistas Municipales del Estado de Jalisco, A.C. (Association of Municipal Chroniclers of Jalisco) recently awarded me the Luis Pérez Verdía medal for my research into the history of the Lake Chapala area.

Comments and corrections welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Loved this bit of history but mainly want to say–this is an award you certainly deserve.

Hi Bill, Thanks for your comment; hope all goes well – HAPPY THANKSGIVING!

Fascinating history!! Thank you for the time you put into this story!

You’re welcome; thanks for reading and taking the time to comment.

Hi, I wonder if the name Seimandi at the time Alberto Braniff and his mother were the owner of the house sounds familiar. Thanks for your answer.

Hi Sergio, Yes, indeed it does. More than one branch of the Seimandi family lived in Chapala at that time. Antonio Seimandi was manager of the Hotel Arzapalo. Juan Seimandi owned or ran the town’s electricity generator, etc. etc. Saludos, Tony.