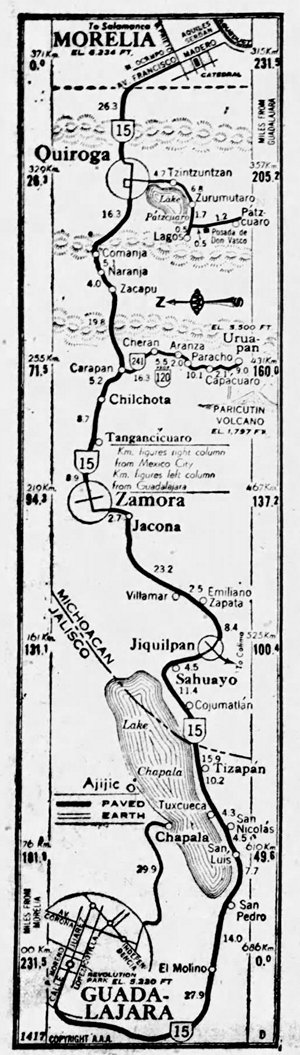

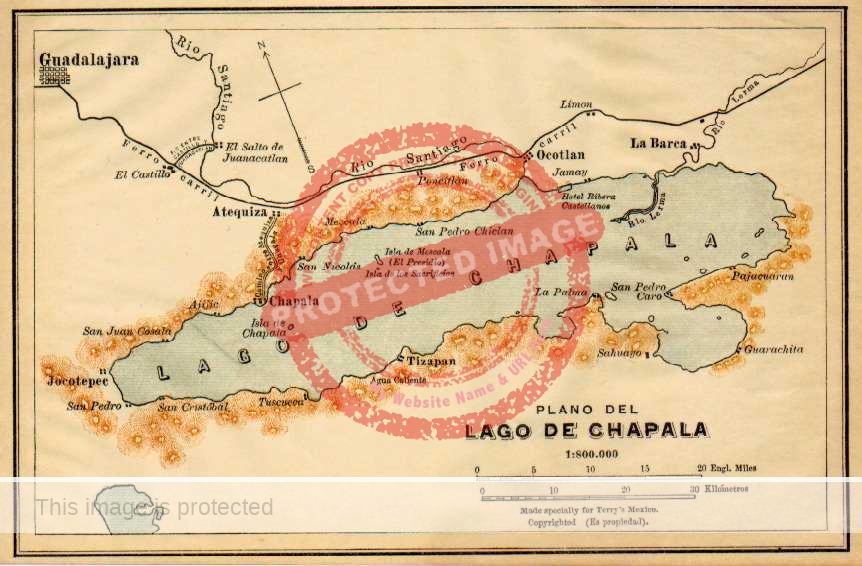

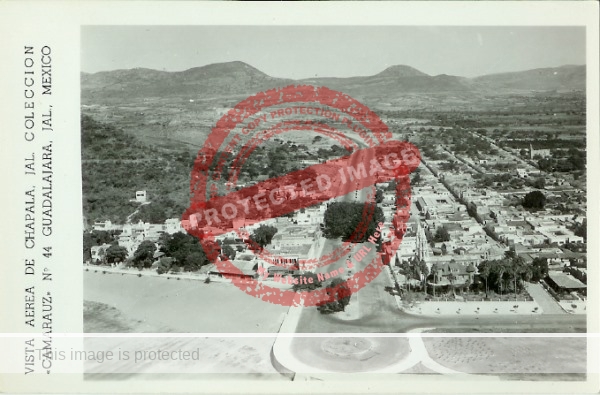

One remarkable Chapala man, Isidoro Pulido, had close links to several of the most important writers and artists ever to live and work at Lake Chapala. According to American poet Witter Bynner, Isidoro was put in jail at the behest of English novelist D. H. Lawrence, before Bynner befriended Isidoro and employed him, while American artist Everett Gee Jackson taught Isidoro how to create near-perfect replicas of ancient archaeological pieces. In addition, Isidoro was immortalized in Arthur Davison Ficke’s novel, Mrs Morton of Mexico, and was the central figure in a US newspaper column published in the 1960s, a decade after his death. How on earth did all this come about?

Though Isidoro (sometimes Ysidoro) Pulido Rentería was born in Tonalá on 17 April 1909, he spent virtually his entire life in Chapala. Isidoro, son of José Refugio Pulido and Clotilde Rentería, had just turned 14 when D H Lawrence and Witter Bynner visited Chapala in 1923, and belonged to a group of young people who hung out having fun at the Hotel Arzapalo and the main beach, hoping to receive tips in exchange for cleaning shoes and running errands. Unfortunately, they entered the hotel dining room once too often, and made more noise than Lawrence (or the Arzapalo’s then manager, photographer Winfield Scott) could tolerate. According to Bynner, Lawrence complained, and Scott arranged for Isidoro and several of his friends to spend the next couple of nights in jail. (D. H. Lawrence’s wife, Frieda, in letters to friends after the publication of Bynner’s memoir, was adamant that no such incident could ever have occurred.)

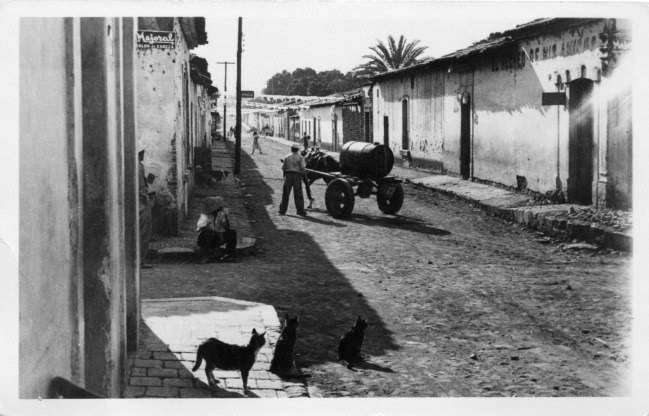

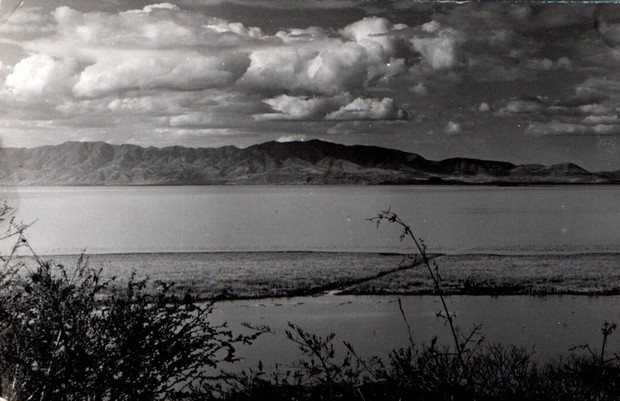

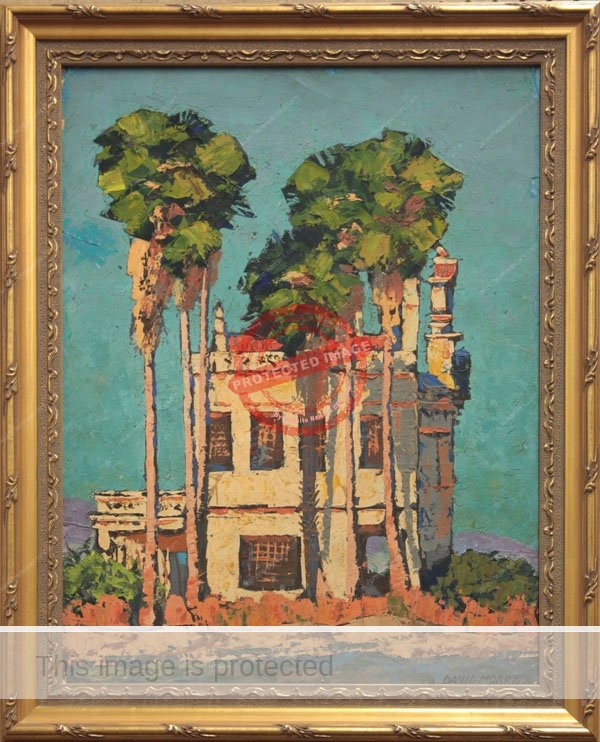

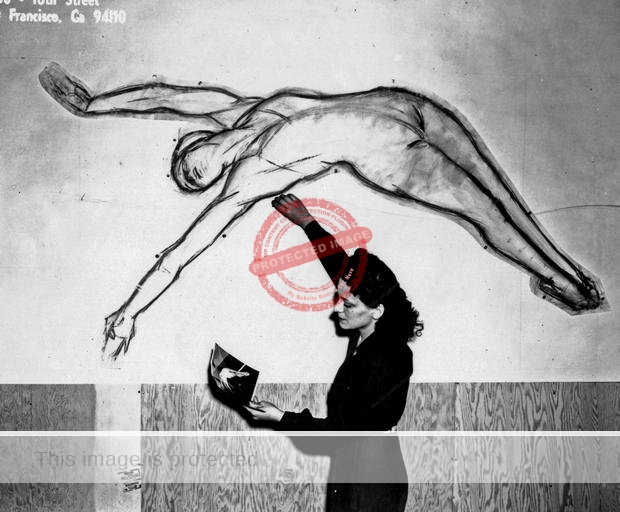

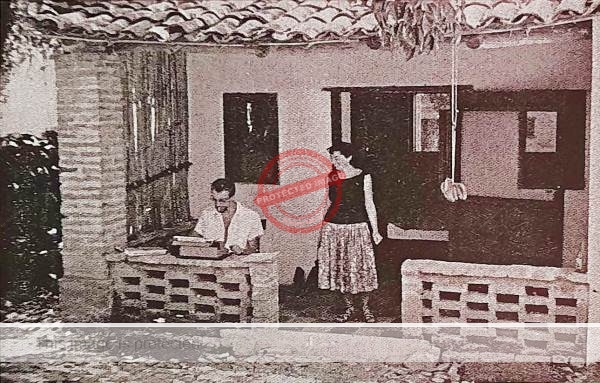

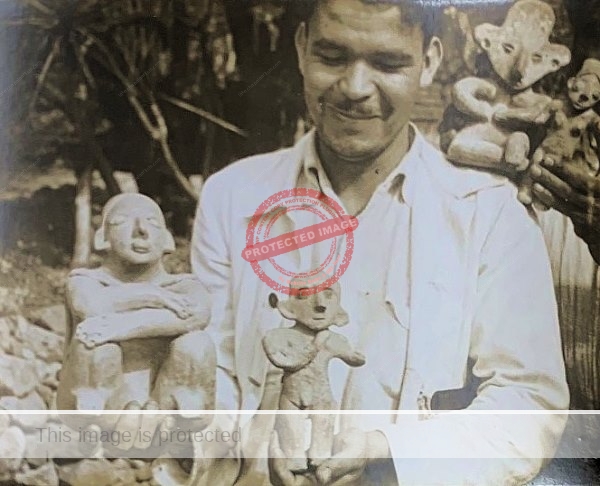

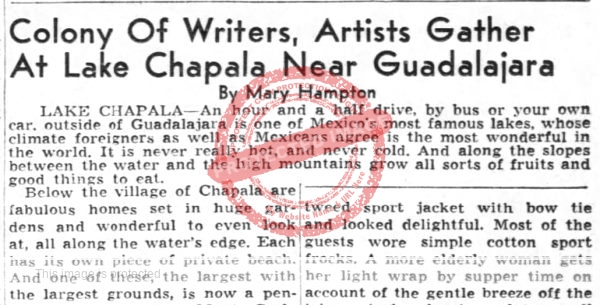

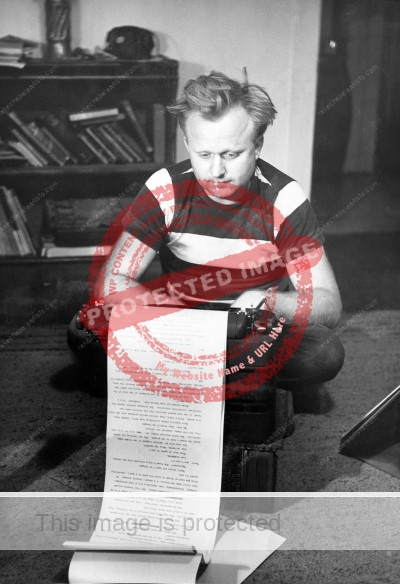

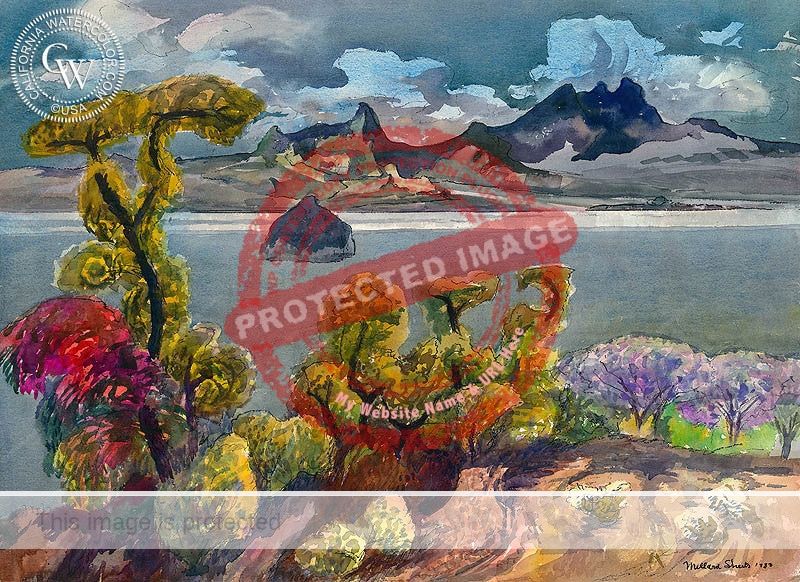

Leo Stanley. 1937. “Ysidoro and his monos.” By kind permission of California Historical Society.

Bynner, who claimed to have witnessed all this, thought that Lawrence had overreacted to the boys and failed to appreciate their youthful enthusiasm. He explained in his memoir Journey with Genius how:

Ysidoro… had come to regard himself as our special room attendant, being adept not only at shoeshining but at filling missions for us with tailor, seamstress, grocer, post office, or bar. In fact we had soon set up a small bar of our own in our front room at the hotel and taught him various skills for mixing drinks. Tequila (with lemon, orange, or grapefruit and mineral water) was the staple.”

Bynner took such a shine to Isidoro that he kept in touch with him over the years and, after buying a house in Chapala in 1940, hired Isidoro (by then married) to be his aide, and to help run the household, mix cocktails and serve meals. Bynner later even built a home for Isidoro’s family.

Another local youngster, José Orozco Aguilar, also benefited from Bynner’s generosity. José originally worked for one of Bynner’s friends, a fellow Harvard graduate named Stanley Lothrop, who had worked for Louis Comfort Tiffany before retiring to Chapala in 1942. After Lothrop’s death a couple of years later, Bynner looked after José and, according to Joe Weston, “taught him how to cook, bartend and handle formal dinner parties, in short all the skills of a majordomo.”

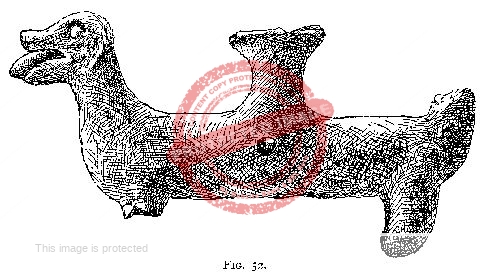

Back in 1923… no sooner had D H Lawrence and his entourage left Chapala than a pair of young American art students—Everett Gee Jackson and Lowell Houser—arrived in town and rented the same house. Jackson and Houser lived at Lake Chapala for several years, and Jackson amassed a collection of small figurines that he analyzed in an article in the 1940s. In his memoir It’s a Long Road to Comondú, Jackson explains how he also taught Isidoro the skills needed to make high quality reproductions of ancient artifacts. And, more than twenty years later, when he returned to Chapala, Jackson was delighted to find that,

Isidoro had become a maker of candy and a dealer in pre-Columbian art in the patio of his house on Los Niños Héroes Street. I did not teach him to make candy, but when he was just a boy I had shown him how he could reproduce those figurines he and Eileen [Jackson’s wife] used to dig up back of Chapala. Now he not only made them well, but he would also take them out into the fields and gullies, bury them, and then dig them up in the company of American tourists, who were beginning to come to Chapala in increasing numbers. Isidoro did not feel guilty when the tourists bought his works; he believed his creations were just as good as the pre-Columbian ones.”

Whether or not anyone really needed Jackson’s help to produce ‘fake’ antiquities is debatable, given that there is plenty of evidence that, by the 1920s, some people were already making—and selling—genuine-looking artifacts to unsuspecting foreign visitors.

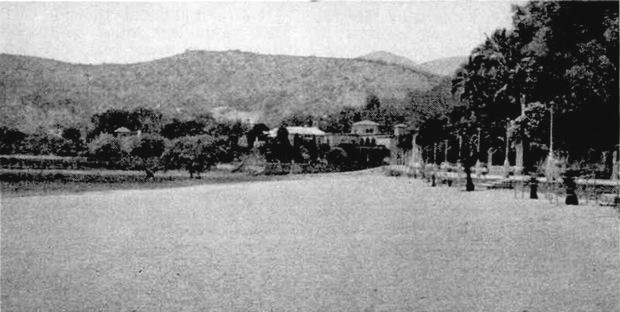

By 1930, Isidoro had married and was living with his wife, Refugio Sotelo, on Calle de los Placeres in Chapala, next door to his parents. Calle de los Placeres is a short street that runs from Avenida Hidalgo (the highway to Ajijic) up the lower slopes of Cerro San Miguel. Two years later, Isidoro and his wife were heartbroken when their daughter Estela fell ill and died before her first birthday.

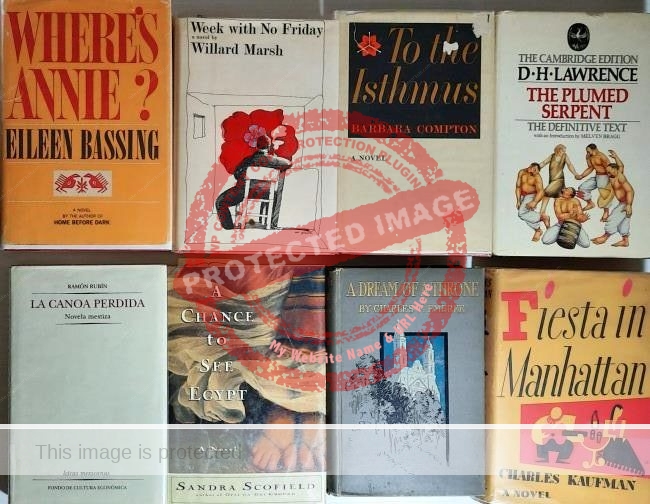

Bynner had continued to revisit Chapala periodically, and he rented a house there for several months in 1934, over the 34-35 winter, and invited close friends—poet Arthur Davison Ficke and his wife, Gladys Brown—to join him. The visit gave Ficke the subject matter for his one and only novel Mrs Morton of Mexico, in which most of the characters are closely based on real people who lived in Chapala at the time. Isidoro, described as a carpenter named “Ysidoro Juarez,” plays an important cameo role in the novel in connection with “The Holy Painting of Jocotepec.”

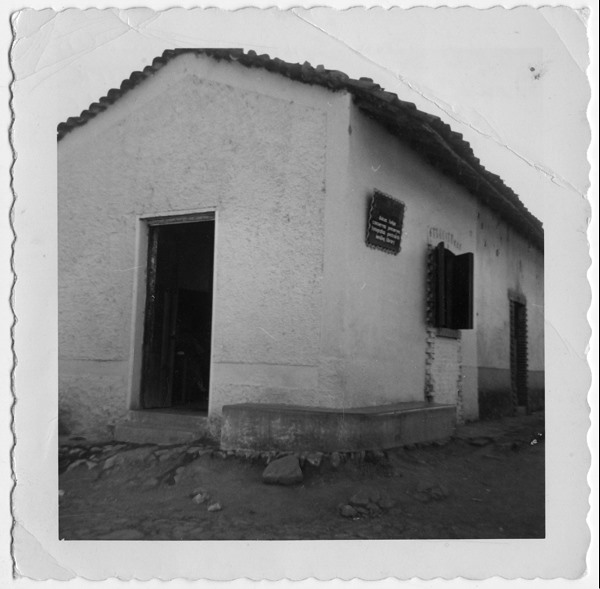

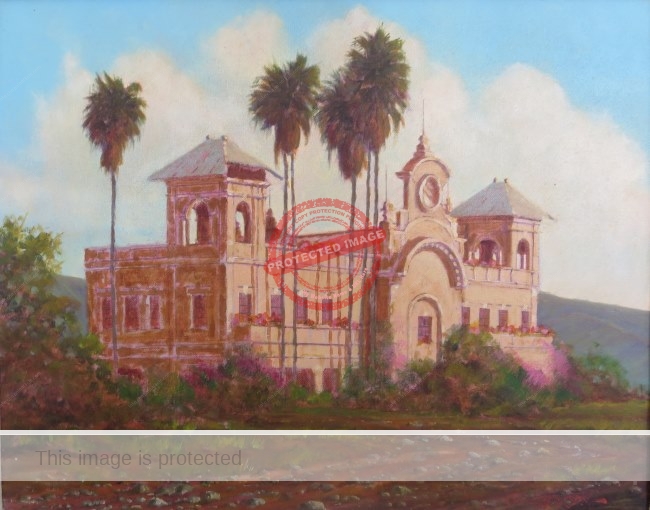

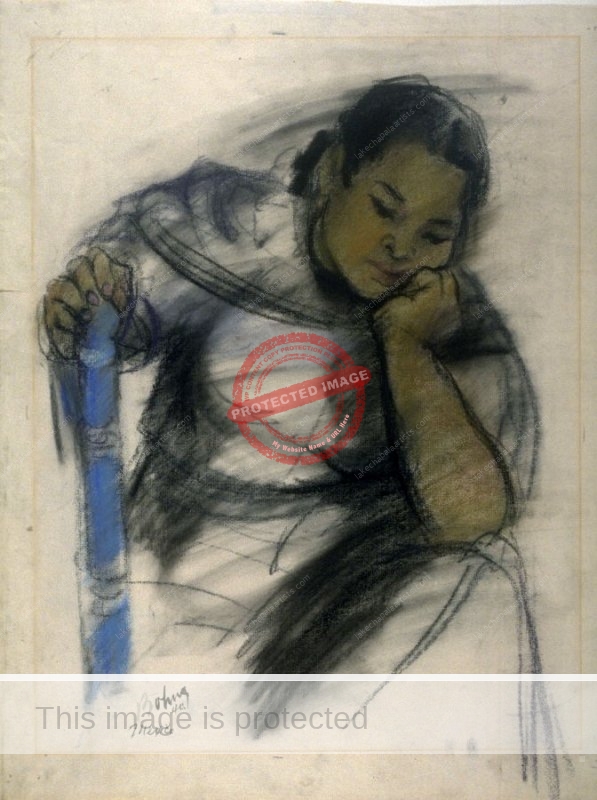

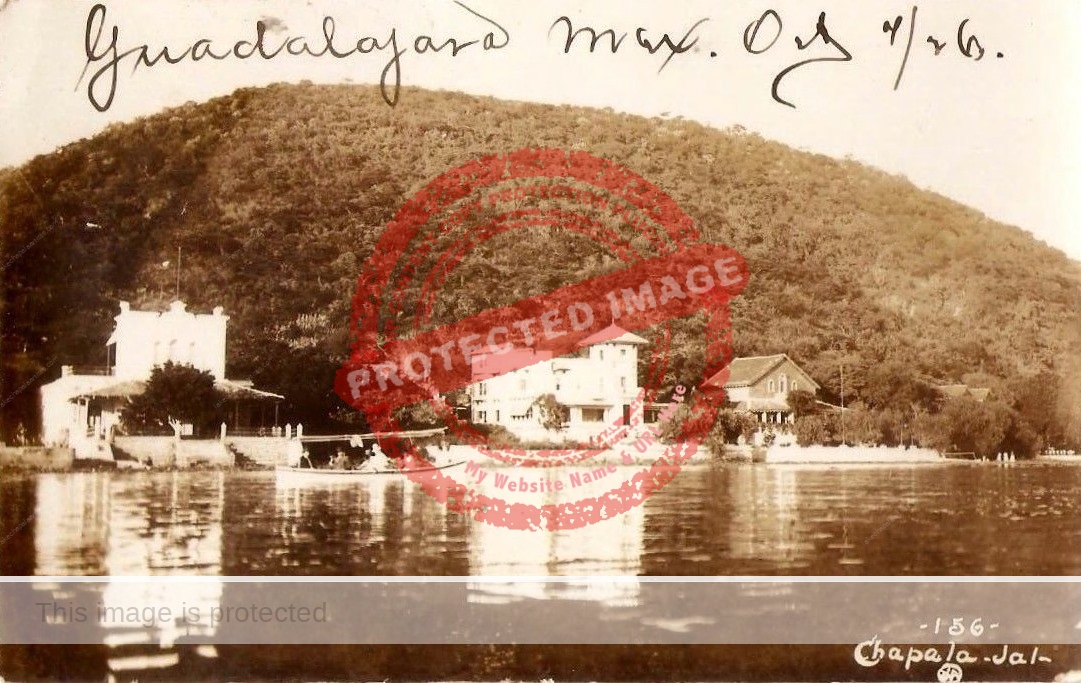

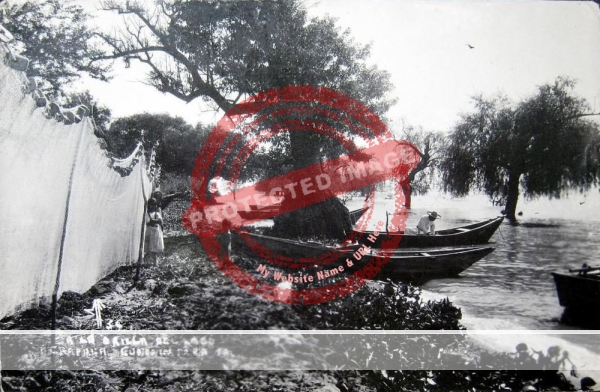

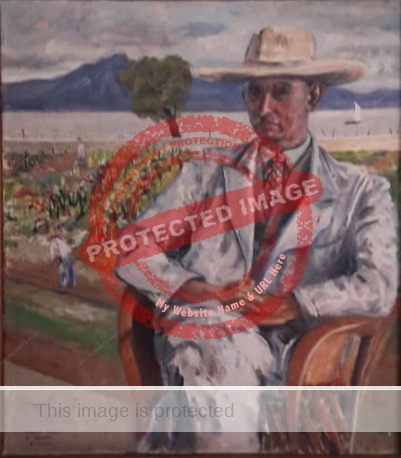

Leo Stanley. 1937. “His family.” Family of Isidoro Pulido. By kind permission of California Historical Society.

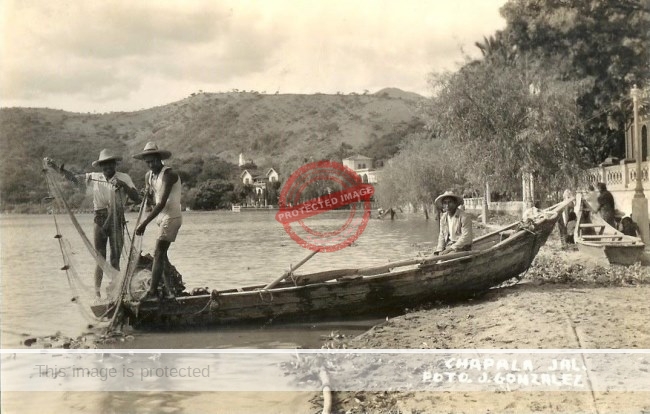

In 1937, Californian prison doctor Leo Stanley visited Chapala. He became sufficiently interested in ancient artifacts to seek out a local to help him find and excavate likely locations. He visited Ysidoro’s hut on the side of Cerro San Miguel, and found Ysidoro, “perhaps twenty-five years of age,” to be bright, intelligent and extremely cordial. Isidoro showed Stanley all manner of stone idols, figures, toads, even cattle, and various letters from the tourists who had visited him, including Witter Bynner and a Mrs W. F. Anderson, of Monterey, California.

Isidoro’s wife had just given birth to the couple’s fourth child, but was far from well. Stanley returned the next day to examine her, and offer advice about her care, but sadly, she died a month later.

Stanley took several photos of Isidoro and his account of their joint search for idols—and of their eventual ‘success’—is an entertaining read.

Bynner bought a house in Chapala in 1940. Three years later, he was in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and about to set out for Chapala with his partner Bob Hunt, when he received a letter from Isidoro, reporting that there had been a big earthquake, felt everywhere from Mexico City to Chapala:

“We are scared now, because this morning, early about three o’clock, we heared [sic] many thunders under the earth. It is eight and the thunders are heared yet. Yesterday about the same time we had an earthquake. Many people got up immediately and ran out of the houses. All the dogs in the town barked and the hens fled from their roosts.”

Fortunately, Bynner’s vacation home survived without any serious damage.

In the 1950s, Texas-based journalist Kenneth McCaleb lived in Chapala for several years. In a newspaper column some years later, McCaleb recalled how he had known a very good faker of antiquities in Chapala, named Isidoro, who “specialized in the familiar pre-Columbian ‘primitive’ ceramic figurines of ancient Mexico.” While the aging process was a secret, Isidoro would guide customers to “places where, after some healthful exercise, he dug up his own archaeological objects.”

McCaleb was prone to some embellishment for journalistic impact, as emerges from his account of Isidoro’s demise:

Something of a ladies’ man, Isidoro was on a trip to Manzanillo in a gay mixed company of friends, when he died. Burial is mostly on the spot in Mexico and his friends, unwilling to see him laid to rest far from home (Manzanillo is in the state of Colima), hit upon a plan. They sat him up in the back seat of his car and drove him to Chapala, where his widow, Carmen, saw to it that he was properly interred.”

In fact, the reality, based on the official registration of Isidoro’s death, is far more mundane. Isidoro may have been in Manzanillo but died in a hospital in Autlán on 29 August 1956.

It is truly remarkable that a single Chapala resident named Isidoro Pulido, whose adventurous and humble life lasted less than half a century, links together some of the most significant authors and artists ever associated with Lake Chapala.

Isidoro Pulido Rentería (1909-1956): Que en paz descansa.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Several chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village offer more details about the history of the artistic community at Lake Chapala.

Acknowledgment

My sincere thanks to Frances Kaplan, Reference & Outreach Librarian of the California Historical Society, and to the California Historical Society for permission to reproduce the images used in this post.

Sources

- Witter Bynner. 1951. Journey with Genius: Recollection and Reflections Concerning The D.H. Lawrences. New York: The John Day Company.

- Arthur Davison Ficke. 1939. Mrs Morton of Mexico. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1987. It’s a Long Road to Comondú. Texas A&M University Press.

- Kenneth McCaleb. 1965. “Conversation Piece.” Corpus Christi Times, 27 Jan 1965, 14.

- Santa Fe New Mexican: 11 Mar 1943, 3.

- Leo L. Stanley. 1937. “Mixing in Mexico.” (2 vols). Leo L. Stanley Papers, MS 2061, California Historical Society.

- E. W. Tedlock (ed). 1961. Frieda Lawrence. The memoirs and correspondence. London: Heinemann.

- Joe Weston. 1972. “Lakeside Look”, Guadalajara Reporter, 10 June 1972, 11-12, 27.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.