Many artists and authors have visited Lake Chapala in search of, or in homage to, their literary or artistic idols. But what about those who have also spent time collecting ancient stone and pottery idols and artifacts? There are far more members of this latter group than I first thought.

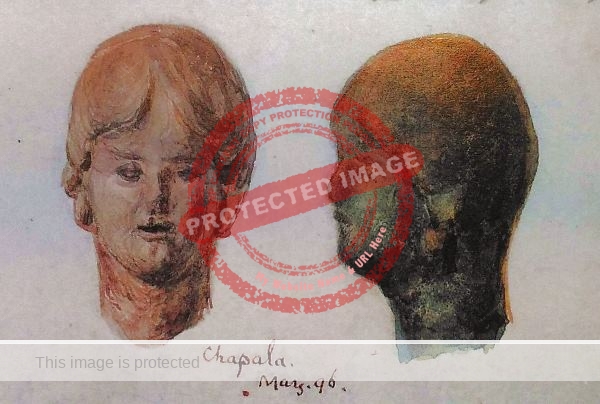

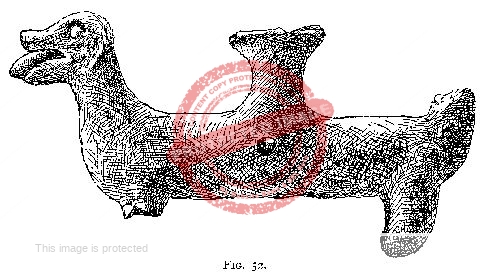

The first academic report of such artifacts in the international press was anthropologist Frederick Starr‘s short, illustrated booklet titled The Little Pottery Objects of Lake Chapala, Mexico, published in 1897. Starr, who visited Chapala over the winter of 1895-96, credited Francisco Fredenhagen with having introduced him to archaeological pieces from the western end of the lake, and suggested a simple typology for the different kinds of objects he had examined. Starr’s collection of ‘miniature pottery’ now resides in Harvard University’s Peabody Museum. Professor Starr’s handwriting may explain why several items are recorded as having been collected in “San Juan Coyala,” instead of San Juan Cosalá!

Fig 52 of Starr (1897)

(Note that, while collecting ancient artifacts as souvenirs and removing them from Mexico was a common practice at the time, it can now result in severe legal consequences.)

Coincidentally, Starr’s visit to Chapala came only a few weeks after a major international conference of ‘Americanistas’ in Mexico City. Several of the attendees had close links to Lake Chapala, including:

- Lionel Carden, the British consul to Mexico Lionel Carden, who was building a house (Villa Tlalocan) in Chapala.

- New Orleans poet Mary Ashley Townsend and her daughter, Mrs Cora Townsend de Rascón: Cora bought Villa Montecarlo in Chapala for her mother that year (1895) as a Christmas gift.

- Ethnographer Jeremiah Curtin, who left us an unforgettable description of meeting Septimus Crowe, the eccentric Englishman and pioneer foreign settler in Chapala, on the train home from the conference.

- San Diego language teacher Eduardo H Coffey, who broke the first news in English of a giant whirlpool that struck the western end of Lake Chapala in January 1896.

- Historian Luis Pérez Verdía, who (in 1904) began building the iconic Victorian-style house close to the church now commonly known as Casa Braniff.

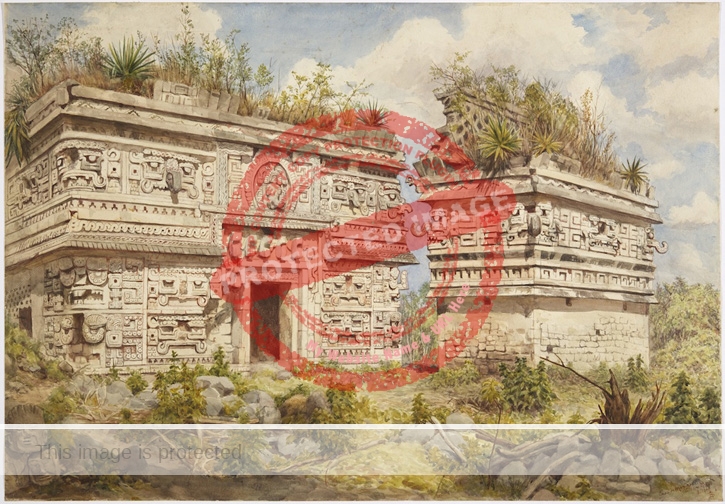

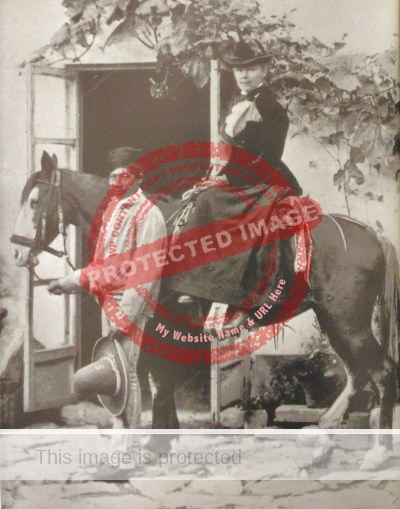

The female English artist and amateur archaeologist Adela Breton, an intrepid traveler who presented papers at later Americanistas’ conferences, also visited Chapala in 1896 and collected a few pottery items. She is best remembered today for having recorded ancient Mayan murals and friezes; in some cases the originals no longer exist, and her magnificent drawings and watercolors are the best record we have of these artistic and cultural treasures.

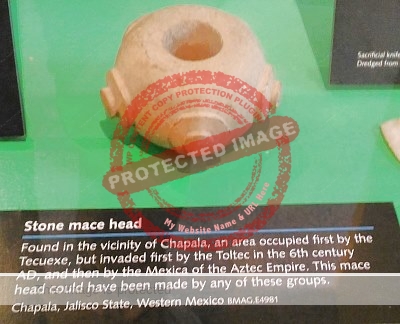

Also visiting Lake Chapala in the 1890s was Norwegian anthropologist Carl Lumholtz, though his findings were not published until 1902. He recorded excavations near Chapala, and the finding of two ‘ceremonial hatchets.’ As we shall see shortly, Lumholtz also apparently bought several ancient artifacts, some or all of which may have been fake.

American journalist George W Baylor described in a 1902 article about Chapala how tourists staying at the Hotel Arzapalo would walk along the beach each morning,

examining the water’s edge closely for ollitas and various kinds of toys which are washed up every night from the lake. Some represent bake ovens, chairs, ducks or geese, volcanoes, and after a storm they are quite plentiful, and an early rise and race is made to get them. They can be bought quite cheap but most every visitor wants to say, ‘I found this on the beach at Lake Chapala.’ One [explanation] is that there was at one time an island in front of Chapala on which there was quite a populous city, and say that this is more than likely, as innumerable pieces of porous burnt rock keep washing ashore.

Another probable explanation is that those three million people that have lived on the borders of the lake since the year 1, threw those toys into the water to propitiate their god of water and rain, Tlaloc, and from the quantities that are carried off by tourists and others annually, each of the three millions of ancients must have put in a bushel apiece. They are made of yellow and blue clay, and burned, and occasionally of stone.

Horrible figures of idols come from the foothills, where in ages past were probably pueblos swarming with Indians. Others are dug from the banks of arroyos in a white cement. Others well, they are manufactured up to date and are sold to innocent parties as contemporaneous with Adam and Eve – nothing later than Montezuma.”

American artists Everett Gee Jackson and Lowell Houser lived for several years in Chapala in the mid-1920s. Jackson amassed his own collection of figurines from Chapala, and published an analysis of them in 1941. In his 1987 memoir It’s a Long Road to Comondú, Jackson also explains how he taught a local boy, Isidoro Pulido (about whom more later), how to make reproductions of figurines! On a return visit to Chapala in 1950, Jackson was delighted to find that,

Isidoro had become a maker of candy and a dealer in pre-Columbian art in the patio of his house on Los Niños Héroes Street. I did not teach him to make candy, but when he was just a boy I had shown him how he could reproduce those figurines he and Eileen [Jackson’s wife] used to dig up back of Chapala. Now he not only made them well, but he would also take them out into the fields and gullies, bury them, and then dig them up in the company of American tourists, who were beginning to come to Chapala in increasing numbers. Isidoro did not feel guilty when the tourists bought his works; he believed his creations were just as good as the pre-Columbian ones.”

Whether or not the locals really needed Jackson’s help to produce ‘fake’ antiquities is debatable, given Baylor’s testimony that even at the very start of the twentieth century some people were already making—and selling—genuine-looking artifacts to unsuspecting foreign visitors.

German-born artist Trude Neuhaus also first visited Chapala in the mid-1920s, as part of her preparations for a show in New York in 1925. The New York Times reported that the exhibition, previously shown at the National Art Gallery in Mexico City, included “paintings, water colors and drawings of Mexican types and scenery,” as well as “Aztec figurines and pottery recently excavated by the artist in Chapala, Mexico.”

Poet and novelist Idella Purnell, born in Guadalajara, had studied under American poet Witter Bynner at the University of California, and played a key role in the decision of English novelist D. H. Lawrence to visit Chapala in 1923. Purnell later penned a delightful, and moving, story, “The Idols Of San Juan Cosala,” for the American Junior Red Cross News.

Five years after American anthropologist Elsie Crews Parsons visited Chapala in 1932, she wrote a short paper entitled “Some Mexican Idolos in Folklore.” She cast doubt on the authenticity of the stone ídolos (idols) collected by some previous anthropologists and ethnographers, writing that, ever since the 1890s there has been,

at this little Lakeside resort a traffic in the ídolos which have been washed up from the lake or dug up in the hills back of town, in ancient Indian cemeteries, or faked by the townspeople. An English lady who visited Chapala thirty-nine years ago quotes Mr. Crow[e] as saying that the ídolos sold Lumholtz were faked, information that the somewhat malicious Mr. Crow[e] did not impart to the ethnologist.”

The identity of the ‘English lady’ referred to by Parsons is unclear. The most likely candidates are either the Honorable Selina Maud Pauncefote, daughter of the British Ambassador in Washington, or Adela Breton, both of whom visited in 1896.

While Parsons doubted the authenticity of Lumholtz’s collection, she was convinced that the items collected at about the same time by Frederick Starr were definitely genuine.

Californian prison doctor Leo Stanley visited Lake Chapala in 1937. He was sufficiently intrigued by the ancient artifacts he saw to seek out a local to help him find and excavate likely locations. In one of those coincidences that are seemingly inevitable in real life, the local was ‘Ysidoro’, the young man befriended years earlier by Everett Gee Jackson! Stanley’s account of the effort involved in hunting for idols with Isidoro Pulido—and of their eventual ‘success’—is well worth the read.

Leo Stanley. 1937. “Digging for Treasure.” By kind permission of California Historical Society.

English author Barbara Compton visited Lake Chapala in 1946. One of the main characters in her semi-autobiographical novel To The Isthmus is an idol hunter and fellow guest at Casa Heuer who regularly left Ajijic for a few days at a time to explore new sites. In real life, she later married the man who had given her the inspiration for this character.

In 1948, author Neill James, an avid treasure hunter, explained to a visiting reporter how:

When the water in Lake Chapala is low, you can sit in it waist deep, dig in the sand and bring up miniature idols, medallions, vases, kitchen utensils and other things that the Indians threw into the lake in their worship of the rain god hundreds of years ago.”

Journalist Kenneth McCaleb recalled in a Texas newspaper in 1965 how he had known a very good faker of antiquities in Chapala, who “specialized in the familiar pre-Columbian ‘primitive’ ceramic figurines of ancient Mexico.” McCaleb reported that the aging process was a secret, but that the maker would guide customers to “places where, after some healthful exercise, he dug up his own archaeological objects.” And the name of this faker? None other than our old friend Isidoro!

Unlike the collecting of ancient idols, with their often dubious provenance, there is—I am glad to report—no obvious drawback to my fixation on collecting and profiling the famous authors and artists associated with Lake Chapala!

My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources

- George Wythe Baylor. 1902. “Lovely Lake Chapala.” El Paso Herald, 1 November 1902, 10.

- Adele C. Breton. 1903. “Some Mexican portrait clay figures,” Man, vol 3, 130-133.

- Barbara Compton. 1964. To The Isthmus. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Mary Hirscheld. 1948. “Author in Mexico.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 April 1948, 8.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1941. “The Pre-Columbian Ceramic Figurines from Western Mexico.” Parnassus, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Jan., 1941), 17-20.

- Everett Gee Jackson. 1987. It’s a Long Road to Comondú. Texas A&M University Press.

- Carl Lumholtz. 1902. Unknown Mexico (2 vols). 1973 reprint: Rio Grande Press.

- Kenneth McCaleb. 1968. “Conversation Piece.” Corpus Christi Times, 27 January 1965, 14.

- Elsie Clews Parsons. 1937. “Some Mexican Idolos in Folklore”, The Scientific Monthly, May 1937.

- Idella Purnell. 1936. “The Idols Of San Juan Cosala.” American Junior Red Cross News, December 1936.

- Leo L. Stanley. 1937. “Mixing in Mexico.”(2 vols). Leo L. Stanley Papers, MS 2061, California Historical Society. Volume 2.

- Frederick Starr. 1897. The Little Pottery Objects of Lake Chapala, Mexico, Bulletin II, Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via the comments feature or email.