Legendary travel journalist Stanton (Stan) Delaplane (1907-1988) and his family spent the summer of 1970 in Ajijic.

Delaplane was a prolific San Francisco journalist who won a Pulitzer prize in 1942 for his reporting about the proposed ‘State of Jefferson’ (for break-away residents of northern California and southern Oregon) and two National Headliner Awards awards before starting a travel writing career.

His unique style was short staccato sentences. He used few or no adjectives. And wrote invariably with a touch of good humor. Always entertaining. Sometimes in sentence fragments. Admirers lauded his writing as Hemingwayesque. Delaplane claimed it was to help San Francisco Municipal Railway riders who read the paper while jostling on crowded trains.

Delaplane, born in Chicago, Illinois, on 12 October 1907, completed his high school years in California and worked for the San Francisco Chronicle for 53 years, after beginning his career at Apéritif Magazine. During the second world war, he served as a war correspondent in the Pacific. His lasting claim to fame, for many, is for having convinced the owner of the Buena Vista Cafe in San Francisco to start serving Irish coffee (then virtually unknown in the U.S.) at his bar in 1952.

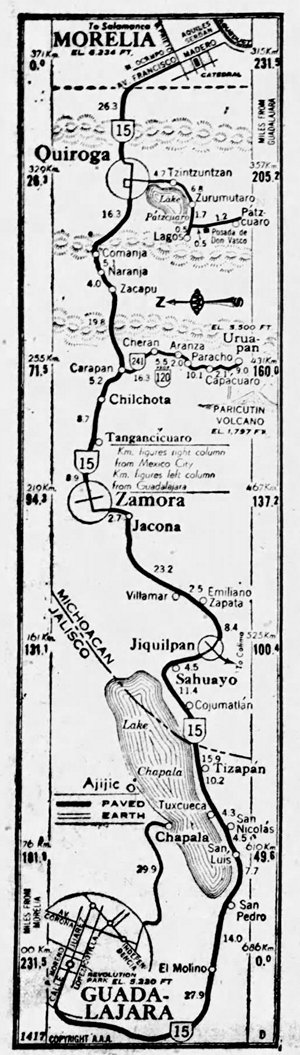

The following year, he turned his talents to travel writing. One of his first syndicated ‘Postcard’ columns was about driving from Morelia to Guadalajara along Highway 15, via Zamora, Jiquilpan, Tizapán el Alto, San Pedro [Tesistán] and El Molino. Conspicuous by its absence is the large town of Jocotepec, at the western end of Lake Chapala, which lies a couple of hundred meters off Highway 15!

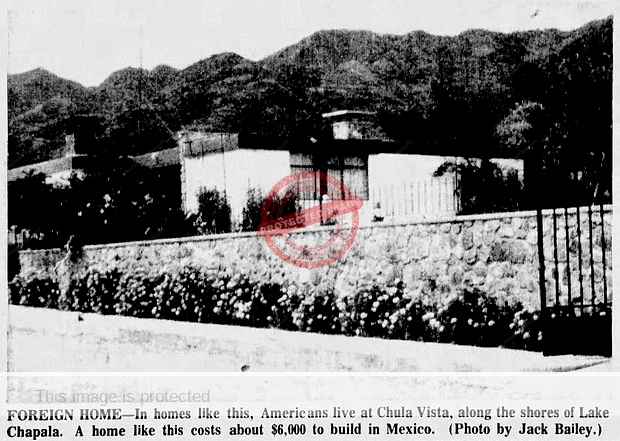

In the same ‘postcard,’ Delaplane told readers that a house could be rented in Ajijic for US$58 a month, and this included “three servants, all your food, tequila and a private launch with crew on Lake Chapala.”

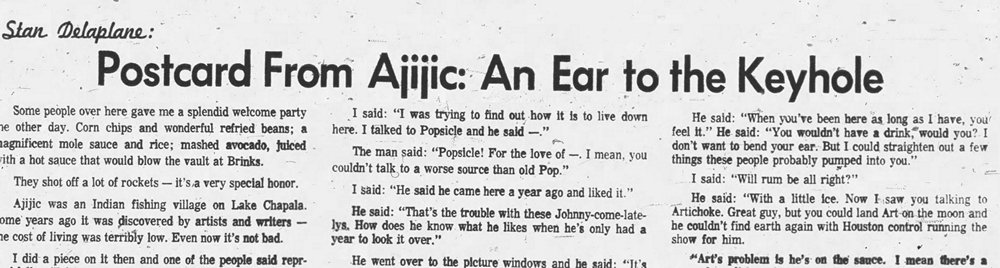

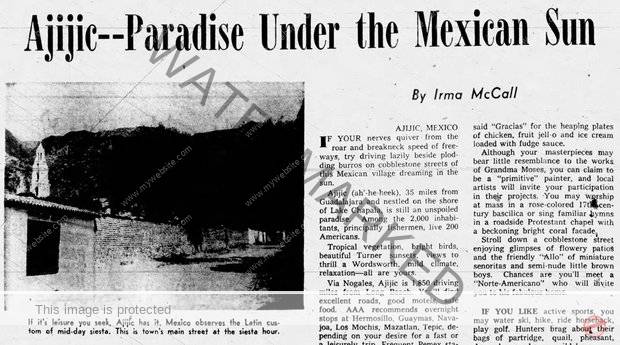

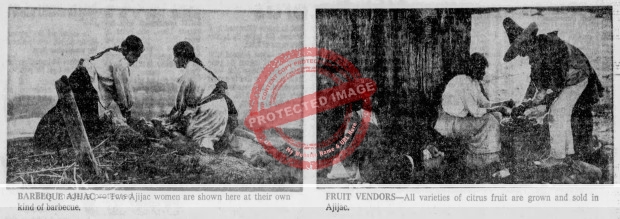

In “Postcard from Ajijic: An Ear to the Keyhole” (1970), Delaplane wrote that, “Ajijic was an Indian fishing village on Lake Chapala. Some years ago it was discovered by artists and writers – the cost of living was terribly low. Even now it’s not bad. I did a piece on it then and one of the people said reproachfully: ‘I hope you don’t do that again. It was very unfair.’ I said, ‘I don’t remember EVER writing about Ajijic. I can’t even remember when I was here.’” (If Delaplane really did write an earlier piece about Ajijic, I have yet to find it.)

The next day, in an entirely different column in a different paper, Delaplane summarized life at Lake Chapala:

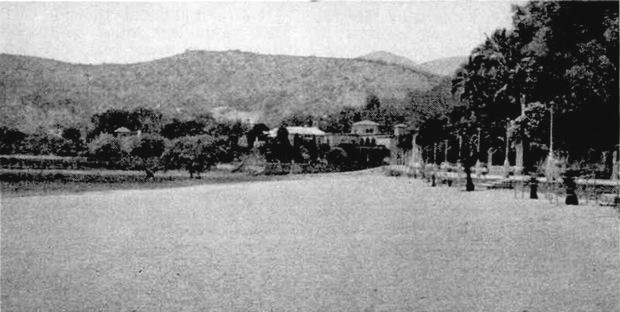

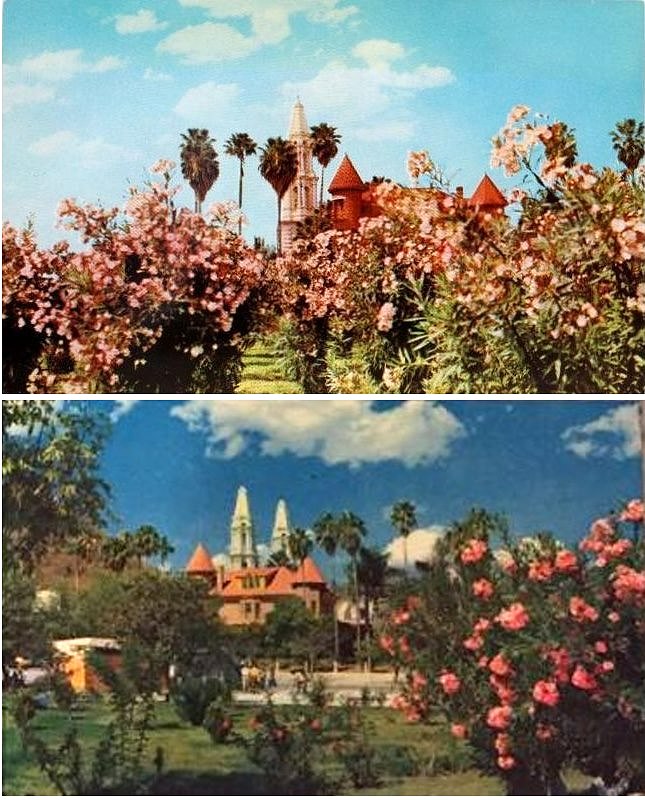

“Ten thousand Americans have moved here where it’s everlasting spring, 5,000 feet up in central Mexico. They swear it’s the pleasantest place, and the best climate in all the world.

They’re mostly retired people-you can’t work in Mexico until you have lived here five years. There are a lot of artists and writers drawn by the low cost of living. (Writing is not considered work. How about that?)

I’ve had several estimates on what it costs: $600 a month covers a modest rented house; a daily maid; food and a few drinks; a party now and then, and a membership in the golf club. Artists and writers do it cheaper. Hippie types? Mexico is conservative. They aren’t very welcome.

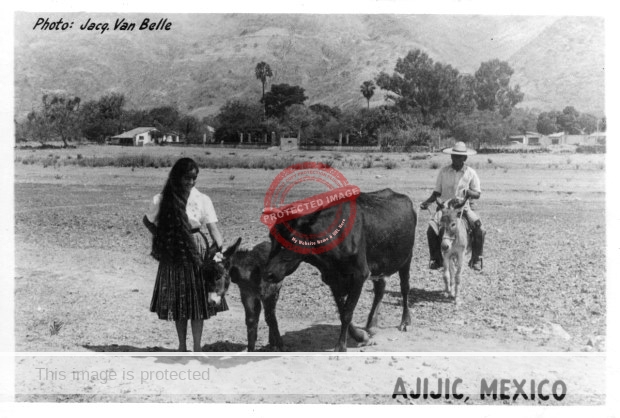

After agreeing it’s the best climate, the argument is WHERE life is best: The village of Ajijic (pop. 3,500) where it all began. Chapala (pop. 7,000) is a pleasant village with a country club residential area five miles out. Jocotepec (pop. 8,000) is an Indian fishing village admired by the art people.”

Everett Herald, 1 Aug 1970. Stan Delaplane.

Returning to Lake Chapala four years later, Delaplane recognized that local life was changing:

We drove over to Lake Chapala the other day. We had a house there four years ago. They [his two children] have fond memories of maids and houseboys and horses they rode . . . . Every Indian village has put in a small supermarket . . . . As this new American money comes in, it changes the land. The cowboy leaves his horse and puts on a waiter’s uniform at the hotel. Village boys caddy on the golf course. The older girls get jobs as maids. More help is needed at the supermarket. Boutiques and curio stores and sandal shops and candle shops spring up.”

In his book Stan Delaplane’s Mexico (1976), Delaplane includes a section titled “Dust on my Knuckles” (echoing the Neill James’ book Dust on my Heart), which opens: “Chapala — The Mexican day dies grandly in the central highlands. Rain clouds tower in the sky. The sun spouts blood and fire and Spanish gold. There’s faraway thunder.”

Delaplane’s final sunset was in San Francisco on 18 April 1988.

Sources

- San Francisco Chronicle: 26 Jan 1953, 17; 23 Aug 1974, 37.

- Stan Delaplane. 1970. “Postcard from Ajijic: An Ear to the Keyhole.” Everett Herald: 1 Aug 1970.

- Stan Delaplane. 1970. “Best in the World.” Tulsa Daily World, 2 August 1970.

- Stanton Delaplane and Stuart Nixon. 1976. Stan Delaplane’s Mexico. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.

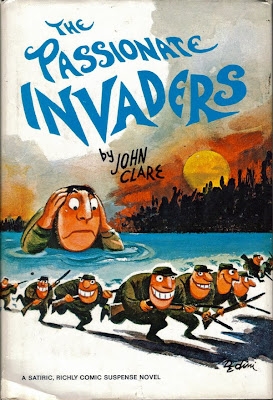

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).