Canadian poet Al Purdy was at the peak of his creative powers when he followed in the footsteps of his idol D. H. Lawrence and visited Lake Chapala in the late 1970s. Since 1923, many Lawrence fans had made their own pilgrimage to Chapala to see first-hand what inspired their great hero. However, Purdy is surely the most famous of all these admirers to do so. Purdy visited Lake Chapala more than once, though the precise timing of his multiple visits has proved impossible to establish with certainty.

His visits to Chapala left their mark on Purdy. In addition to a travel piece about the area, he published a hand-signed, individually-numbered, one-poem “book” entitled The D. H. Lawrence House at Chapala. This collector’s item, a single broadside in an elegant gilt-stamped folder, was published by The Paget Press in 1980, in a limited edition of 44 copies. The book includes a photograph, taken by Purdy’s wife, Eurithe, of the plumed serpent tile work above the door of the Lawrence house at Chapala.

According to David Bidini, Purdy’s travel article about Chapala was one of only three items the great poet kept in full view on the wall of his studio in Ameliasburgh, southern Ontario. The other two items were “a 1990 flyer celebrating Al Purdy Day” and “a New Canadian Library poster featuring its Famous Canadian Writer titles, many of them Purdy’s.” However, the photos of Purdy’s studio shown in the full length documentary Al Purdy was Here paint a different picture, one of a cluttered studio with photos, posters and writings vying for space on crowded walls hemmed in by overflowing bookshelves. His filing system, such as it was, comprised folders stuffed into cardboard boxes.

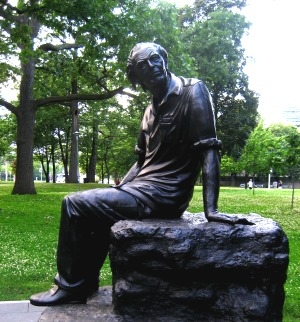

Statue of Al Purdy in Queen’s Park, Toronto. Bronze, 2008. Photo: Marisa Burton.

Purdy was a massive fan of Lawrence, and a bust of the English author had a prominent position on his desk. The English novelist was seemingly listening to every click-clack of Purdy’s typewriter and watching his every key stroke. Like his idol, Purdy had a reputation for being somewhat cantankerous and combative, especially to outsiders. Unlike the sickly Lawrence, Purdy was taller, heavier, healthier and outwardly happier. The New York Times obituary for Purdy summed him up as “a lanky writer whose brash, freewheeling ways masked a love for language”

Alfred Wellington Purdy was born on 30 December 1918 at Wooler, Ontario, and died 21 April 2000 in Victoria, British Columbia. His pathway to poetry was unconventional. He left high school after only two years (but not before selling his first poem to the high-school magazine, Spotlight, for a dollar), rode the rails during the Great Depression, and took a variety of menial jobs in British Columbia before joining the Royal Canadian Air Force (R.C.A.F.) when the second world war broke out.

Purdy married Mary Jane Eurithe Parkhurst in 1941. After six years in the R.C.A.F., Purdy and his wife settled in British Columbia. In 1956, they moved back east, first to Montreal and then to Ameliasburgh in southern Ontario. This was where Purdy honed his literary skills and became acknowledged as a “poet of the people”. Growing acclaim for his work won him several Canada Council Grants, enabling travel to write in locales ranging from British Columbia and Baffin Island (1965) to Greece (1967). In later life, in addition to visiting Mexico on several occasions, the Purdys divided their time between Ameliasburgh and Sydney (on Vancouver Island).

During his long writing career, Purdy published more than 30 books of poetry, a novel (Splinter in the Heart, 1990) and an autobiography (Reaching for the Beaufort Sea, 1993) plus dozens of radio plays, dramas and book reviews. His best known poetry collections include The Cariboo Horses, which won him a Governor General’s Award for poetry in 1965, The Stone Bird (1981), Piling Blood (1984), and The Collected Poems of Al Purdy, 1956-1986, which earned him a second Governor General’s Award in 1986. Purdy was awarded the Order of Canada in 1982 and the Order of Ontario in 1987.

In her foreword to a collection of Purdy’s poems, Margaret Atwood praised how “Purdy is always questioning, always probing, and among those things that he questions and probes are himself and his own poetic methods. In a Purdy poem, high diction can meet the scrawl on the washroom wall, and as in a collision between matter and anti-matter, both explode.” According to a much earlier CBC radio program Introducing Al Purdy (1967), “what he said startled people. His unconventional works poeticized barroom brawls, hockey players and homemade beer. Al Purdy’s work forced Canadians to re-evaluate their understanding of poetry and themselves.”

Purdy made numerous trips to Mexico between the early 1970s and the late 1980s. He was quick to admit he loved the country. Unimpressed by an editorial in the Globe and Mail to the effect that Mexicans were not especially friendly, Purdy wrote to say that it was necessary to draw a distinction between the Mexican people who were “as friendly and cordial as any you could wish to meet” and the less friendly attitudes of Mexican police and officialdom.

Purdy used his trips to Lake Chapala as part of a creative process to probe the connections between Lawrence and Chapala. In 1979, he wrote to fellow Canadian poet Earle Birney (who had composed poetry at Lake Chapala in the 1950s) describing how he had taken a look at Lawrence’s house in Chapala, “a peeling yellow-stucco two-storey place, with a large section of coloured tiles depicting a plumed serpent, the only trace of Lawrence evident” and was working on “a coupla poems… one of which might turn out to be something.”

Several of Purdy’s later poems have explicit links to Mexico, D. H. Lawrence and Chapala. These include “D. H. Lawrence at Lake Chapala,” a slightly modified version of the poem used for the single-page book The D. H. Lawrence House at Chapala, published in 1980. “D. H. Lawrence at Lake Chapala” was included in The Stone Bird (1981) and in Beyond Remembering: the collected poems of Al Purdy. The poem reveals at least as much about Purdy and his time at Lake Chapala as it does about Lawrence. The poem opens,

Try to simplify your life

you cannot

try to live a new life

and the old one complicates the new . . .

Other Purdy poems about Lawrence include “Death of DHL,” “Lawrence’s Pictures,” “I Think of John Clare” and “Lawrence to Laurence.”

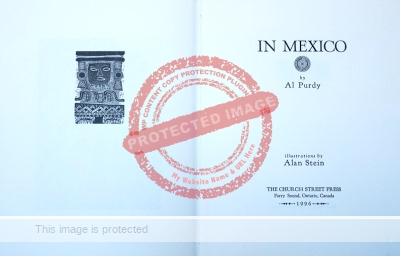

In 1996, Purdy published In Mexico, a hand-printed limited edition of an 80-page poem based on his travels to Mexico with Eurithe, illustrated with 10 fabulous wood engravings by Alan H. Stein.

Purdy’s life-long love of Lawrence culminated in a joint limited edition work with Doug Beardsley entitled No One Else Is Lawrence! A Dozen of D.H. Lawrence’s Best Poems (1998).

Ameliasburgh, his home for so many years, has embraced its fame as the place where Purdy produced his finest poems. In 2001, the local library was renamed the Al Purdy Library. His name has also been given to the street that leads to the town cemetery (and his tombstone). Purdy’s A-frame, with its separate writing studio, overlooking the lake, has been restored and now operates a summer residency program for aspiring writers.

Al Purdy’s papers are divided between several university archives, with the largest collection held by Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the help kindly offered by Eurithe Purdy in clarifying the chronology of her visits to Mexico with her husband.

Sources

- Doug Beardsley and Al Purdy (introduction and commentary). 1998. No One Else Is Lawrence! A Dozen of D.H. Lawrence’s Best Poems. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, B.C.

- David Bidini. 2009. “Visit to poet Al Purdy’s home stirs up more than a few old ghosts.” National Post, 30 October 2009.

- Nicholas Bradley (ed). 2014. We go far back in time: the letters of Earle Birney and Al Purdy, 1947-1987. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, B.C.

- James Brooke. 2000. “Al Purdy, Poet, Is Dead at 81; A Renowned Voice in Canada.” New York Times, 26 April 2000.

- Al Purdy was Here. 90-minute documentary. Available via iTunes.

- Al Purdy. 1976. Letter to the editor, Globe and Mail, 26 April 1976, 6.

- Al Purdy. 1980. The D. H. Lawrence house at Chapala. The Paget Press.

- Al Purdy. 1981. The Stone Bird. McClelland and Stewart.

- Al Purdy. 1996. In Mexico. Church Street Press, Parry Sound, Ontario, Canada.

- Al Purdy. 2000. Beyond Remembering – The Collected Poems of Al Purdy. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, B.C. (Forewords by Margaret Atwood and Michael Ondaatje).

- Jeffrey Aaron Weingarten. 2013. Lyric Historiography in Canadian Modernist Poetry, 1962-1981. PhD Thesis, McGill University, 101-2.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in this series of mini-bios are welcome. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.