German-Mexican artist Hans Otto Butterlin (born Cologne, Germany, 26 December 1900) was only six years of age when the family emigrated from Europe to Mexico, living first in Mexico City and then Guadalajara.

During the Mexican Revolution, Otto and his younger brother, Friedrich, were sent back to live with relatives in Germany. Otto attended high school (Gymnasium) in Siegburg, but left school in about 1916 (mid-way through World War I) to join the German military as a one-year volunteer. After military service, Otto entered the University of Bonn in 1919 to study chemistry. The following year he continued his studies at Marburg University, before transferring to the University of Munich, where he was able to pursue his passion for art.

Otto studied briefly at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1920 before moving to Berlin, where he was a member of the group of artists mentored by George Grosz, an influential artist and art educator, best known for his caricatures of Berlin life in the 1920s.

Otto returned to Mexico at the end of 1921 and began a career as an industrial chemist, working at several sugar mills in Jalisco, Sinaloa and the US. In about 1934, Otto moved to Mexico City, and joined the Mexican subsidiary of the German chemical company Bayer AG. While living in Mexico City, Otto was able to indulge his creative passion—painting—which led to him becoming close friends with a number of prominent Mexico City artists.

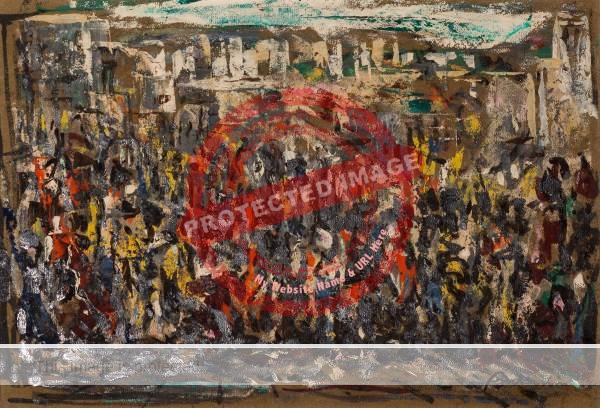

Otto Butterlin. Untitled, undated. Reproduced by kind permission of Monique Señoret.

Otto and his family made their home in Mexico City in a second floor studio built by Mexican architect-artist Juan O’Gorman in the San Ángel Inn area, next door to the studio-home of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. This connection to such dedicated and talented artists undoubtedly fueled Otto’s desire to take his own art more seriously.

In Mexico City, Otto developed his skills in engraving and the production of woodblocks. He also taught art. From 1944 to 1949, Otto taught courses on the materials and techniques of painting at the San Carlos National Academy of Fine Arts, where his students included José Chávez Morado, Luis Nishizawa, Ricardo Martínez and Gunther Gerzso. He also taught techniques of restoration and conservation at the National School of Anthropology and History (Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, ENAH).

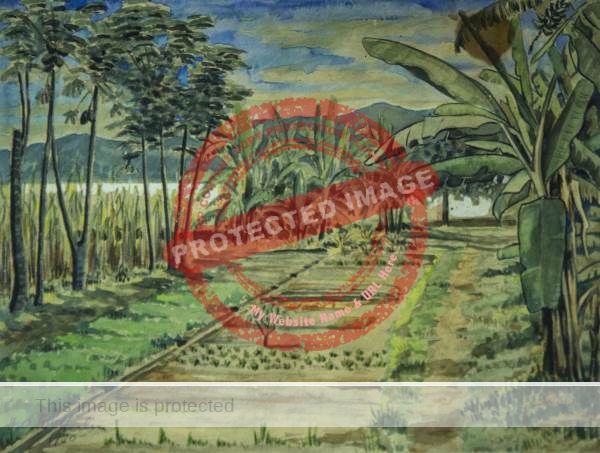

Otto Butterlin. Untitled, undated. Reproduced by kind permission of Monique Señoret.

The first major article drawing public attention to Otto’s art appeared in 1939 on the eve of World War II in Mexican Life, where Albert Helman outlined Otto’s background and critiqued his portraits of indigenous women. Helman rightly concluded that Otto had “become a Mexican not only in nationality but also in his way of thinking and feeling,” and was “the one painter among us to mainly preoccupy himself with the depiction of Mexican folk-types and to pursue in such a depiction a deeper, a psychological as well as physical characterization of the native Indian face.”

Otto held three major solo shows in Mexico City—at the Galería de Arte Mexicano in November 1942, November 1946 and January 1951— all of which were widely praised by critics. A review of the first show called it a “transcendent exhibition” by an artist who had assimilated “all the magical expressionist thrust of modern German art…. makes his own colors, like any conscientious European, and then applies them, with feverish creative passion and haste, on his splendid canvases.” (Mada Ontañón in Hoy). An anonymous reviewer of the third show told readers that “The specialized technique of Butterlin, a king of impressionism with a tremendous strength… is absolutely unmistakable.”

Otto Butterlin. Untitled, 1930. Reproduced by kind permission of Tom Thompson; photo by Xill Fessenden.

Otto and his family lived in Mexico City until the mid-1940s when they moved to Ajijic on Lake Chapala. At that time Ajijic had no art supplies, no galleries, limited electricity, and only one phone line; it was as easy to reach by boat as by road.

Otto died in Ajijic on 2 April 1956, at the age of 55.

Otto’s legacy

Binational and bicultural, Otto Butterlin had a significant influence on Mexican art in the mid-20th century. Yet his life and work have been largely ignored by art historians. German by birth, he became Mexican by choice. Though he lived most of his adult life in Mexico, Mexican writers have ignored his achievements because he was not native-born; Germans have forgotten him because Butterlin, after training as an artist in Germany, left that country in his mid-twenties and never returned.

Otto’s significant contributions to the development of modern Mexican art have been undervalued. For example, his series of powerful portraits—several of them intimate—of indigenous girls and women reveal how Otto was at the forefront of the post-Revolution art movement, one that was finally concerning itself with the nation’s indigenous peoples, landscapes and cultural traditions. This movement, which spawned new artistic techniques and styles, while often linking back to ancient pre-Columbian motifs and designs, also revived modern muralism, which made Mexico world famous as a cradle of artistic creativity.

Otto Butterlin showed a generation of Mexican artists how old-world artistic styles could be applied to new-world subject matter, and how a deep knowledge of chemical processes, paints and materials enhanced an artist’s ability to portray ideas and emotions. Otto’s own art focused more on feelings and emotions than on calculated representational portrayals. His influence helped nudge Mexican art away from realism and towards abstract expressionism.

Otto was generous and perceptive, more interested in art for art’s sake than for remuneration, profit or fame. He worked alongside—and his work was admired by—the greatest artists of his time. Artist, chemist and much more besides, Otto Butterlin left Mexico an extraordinary artistic legacy, one to be treasured, admired and enjoyed.

Acknowledgment

- My sincere thanks to Otto Butterlin’s granddaughter, Monique Señoret, for her hospitality and for giving me the opportunity to see her extensive private collection of his original works.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Would appreciate if you could mention the names of his children and where he lived in Ajijic. Thank you, Dinah DeVry

The Butterlin family had several homes in Ajijic. For more about Otto’s immediate family, please see https://lakechapalaartists.com/?p=1221

I have a 23X29 Butterin painting purchased in Ajijic in the late 1950s. It seems to be called “Lost in the Woods,” and shows a little girl surrounded by terrifying forest images. Bits of paint have flaked away. What should I do with this?.

Exciting! Thanks for reaching out. Can you send me a photo of the painting, please, to this email, – and of the area that is damaged? Are you looking to repair it, or sell it as is, or loan or donate it to the Ajijic Museum of Art, which is opening on 1 June??? Regards, Tony

I have two paintings I am interested to sell.

Responding via email. TB.

Dear Karla, Can you please send me photos via email of the two paintings you are interested in selling?

Can you also share, please, their size, current location (town/city) and how they came to be in your possession?

Thanks, Tony Burton