Why has it taken me so long to write about U.S.-born photographer C. B. Waite and his important contribution to documenting Mexico at the start of the twentieth century? The main challenge has been to unravel the discrepancies and inconsistencies in most previous accounts of his life and work. So, before examining Waite’s major contributions to documenting Mexican history, let’s get some of the more common and egregious misunderstandings out of the way once and for all.

First, C. B. Waite (who signed his work “Waite Photo”) is Charles Betts Waite (1861-1927), not Charles Burlingame Waite, as erroneously claimed in 2007 in Casanova and Konzevik’s major book about Mexican photographers, and—as recently as 2016—in an exhibition catalog published by Mexico’s National University, UNAM. (For the record, Charles Burlingame Waite (1824-1909) was an American writer and judge.)

Secondly, our Charles Waite did not marry “at age 35″ and then move to Mexico “in 1896 with wife and two daughters, Helen and Mary,” as claimed by some, including Francisco Montellano. Charles Betts Waite’s first wife was Alice A. Ironmonger; their only child was Hazel Pearl Waite, born in Los Angeles on 15 June 1885. Waite was on his own when he moved to Mexico in 1897. Three years later he married his second Alice—Alice Mary Cooley (1866–1923)—in Quincy, Illinois, and the new couple made their home in Mexico City.

Thirdly, Waite’s brother was not the “William Waite” murdered on a plantation near Veracruz in April 1912, as sometimes claimed. While C. B. Waite’s own father was, coincidentally, also named William, there is no known familial connection to the man killed in Mexico. Waite’s (only) brother was Frank Dawson Waite (1854–1927), a newspaperman associated with the San Diegan and the San Diego Sun, and considered “one of the ablest and most respected editorial writers in Southern California.”

To add to the confusion, Waite has often been credited with photographs taken by other photographers working in Mexico at the same time. I examine the background and reasons for this in a separate post: Who gets the credit? Charles Betts Waite or Winfield Scott?

Waite’s pre-Mexico life

Charles Betts Waite was born in Ohio on 19 December 1861 to an English-born couple, William and Ann (née Dawson) Waite. On passport and consular documents, he usually named his birthplace as Plymouth, Ohio, but sometimes claimed Auburn Township in Crawford County, Ohio. Either way, he was apparently raised in Plymouth. But, by June 1881, shortly before his 20th birthday, he had moved to California and was working with photographer Henry Ellis Coonley in the San Diego region. He married his first wife, Alice Aldelaid Ironmonger (1860-1948), in 1883. By his late twenties, Waite was credited for photographs published in the San Diego Union and was apparently working as a view photographer for Burdick and Company in Los Angeles.

During the 1890s, Waite’s photographs of ranches and landscapes in Southern California appeared in the Los Angeles-based magazine Land of Sunshine, and he was taking commissions from railroad companies, including the Santa Fe, Los Angeles Terminal, and Mount Lowe Railways. His 1896 voter registration in California puts him at 5’6″ tall, with blue eyes, dark hair, and living at 8 Stockton Street in Los Angeles.

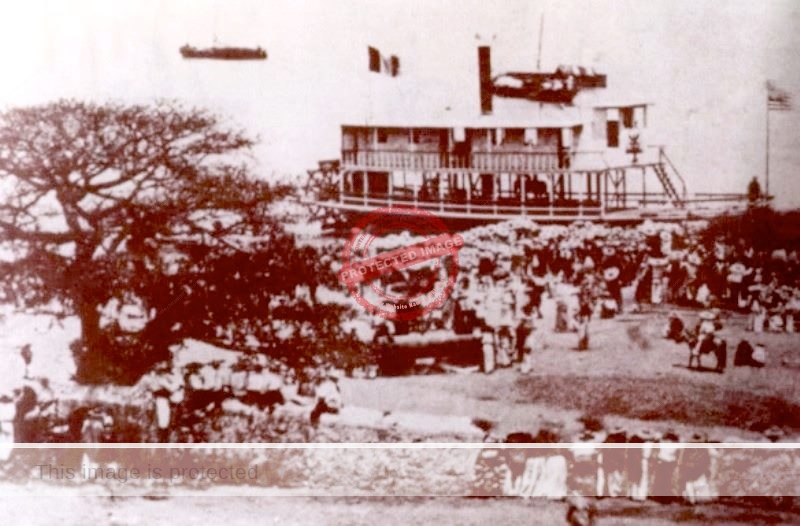

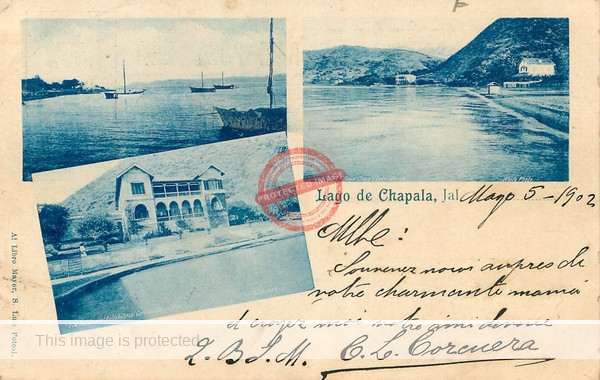

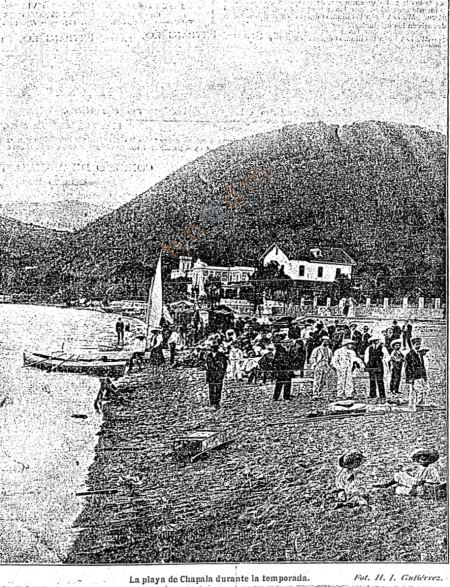

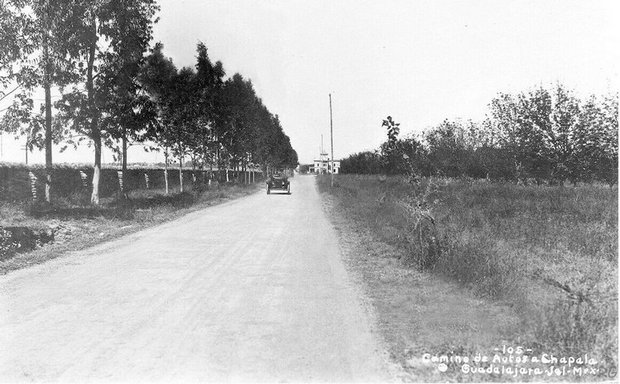

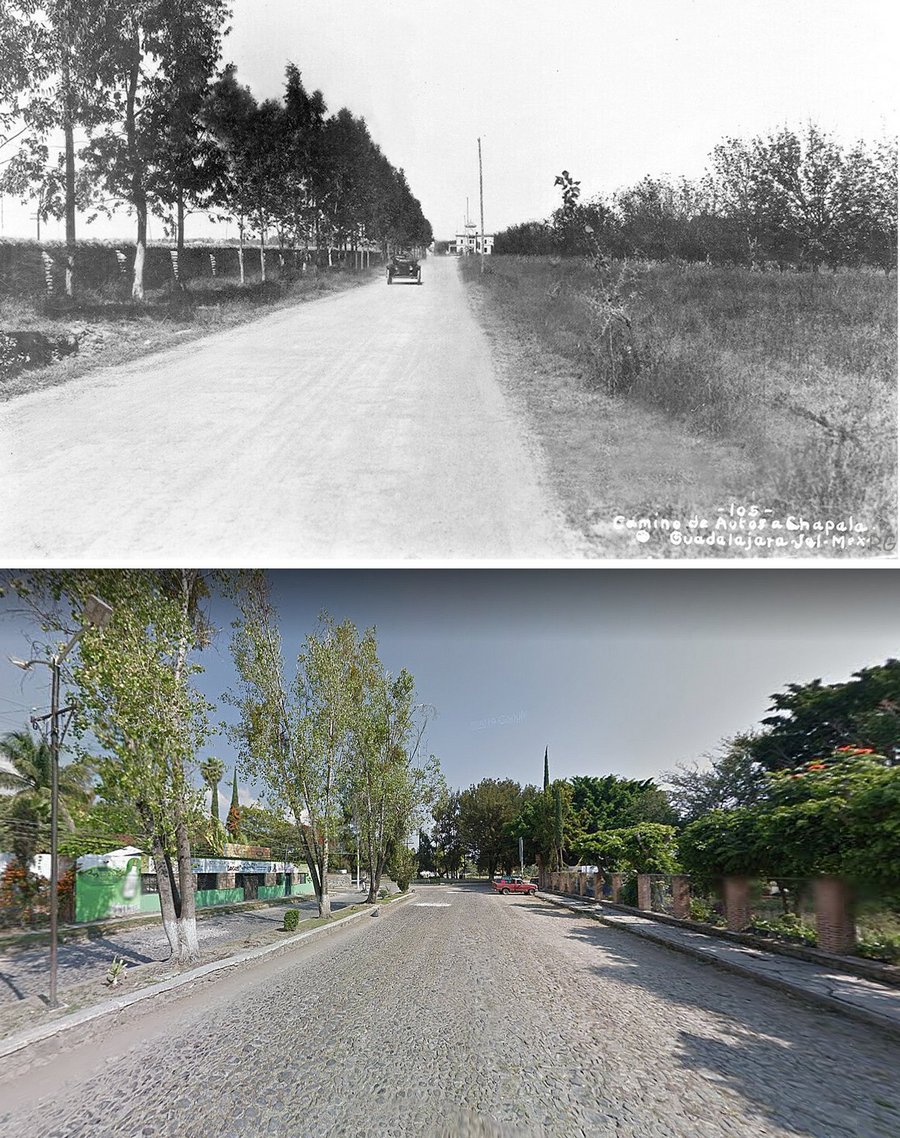

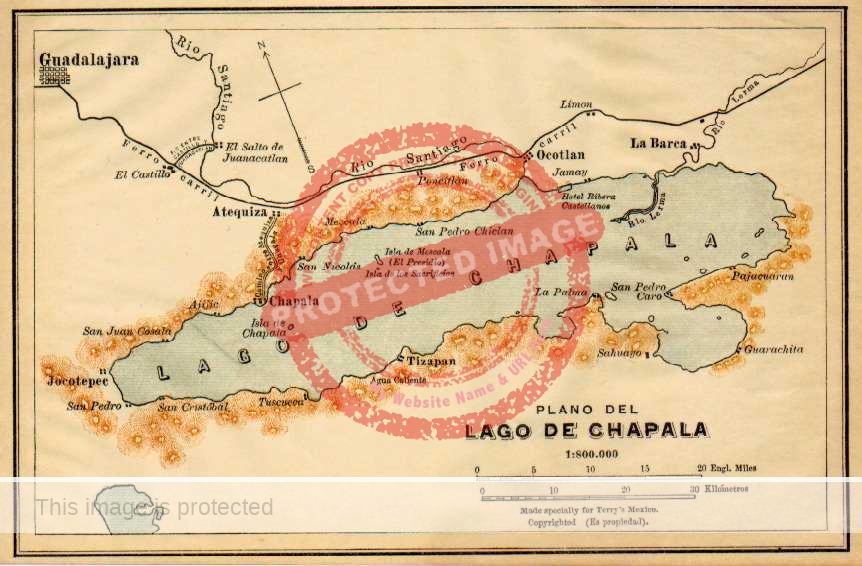

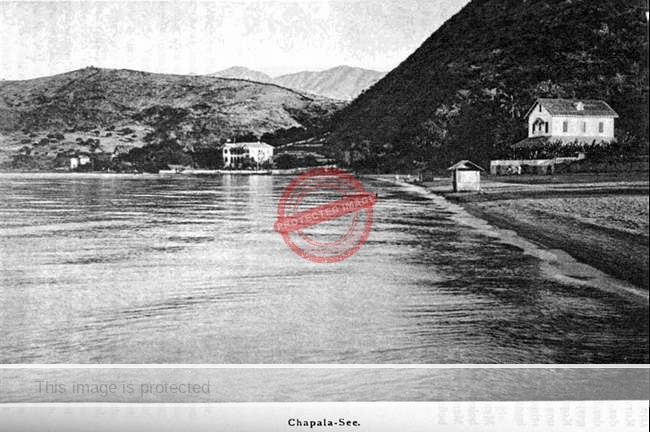

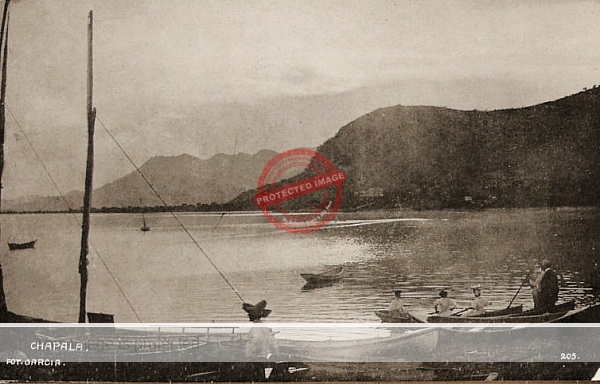

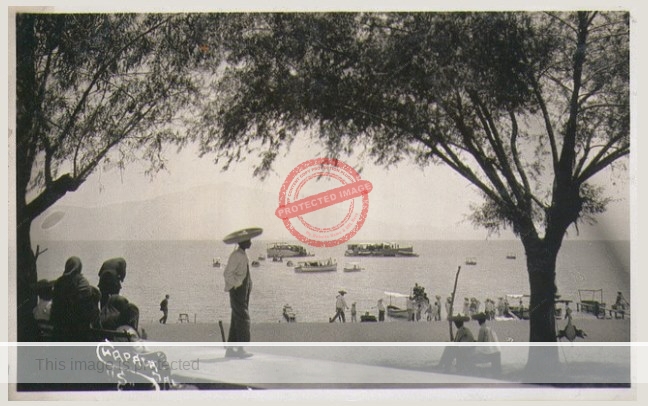

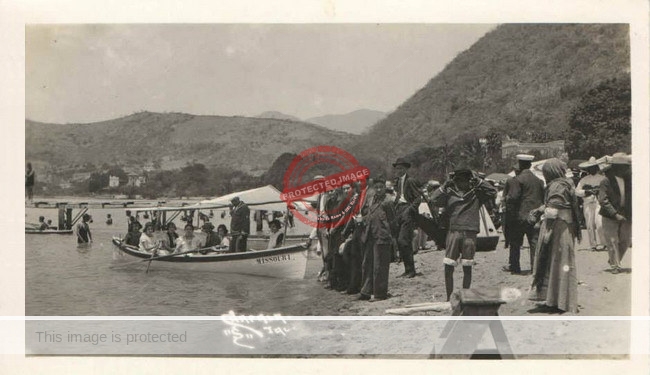

C. B. Waite. Three views of Lake Chapala. Postcard published by Juan Kaiser c 1901, mailed 1902.

In May 1897, Waite left the U.S. for Mexico City, where he established his first studio at Calle de Rosales #200, intending to supply photographs primarily for American magazines. He moved several times during his thirty or so years in the city, and later addresses included San Cosme #8 and San Juan de Letrán #3 and #5.

Within months of arriving in Mexico City, Waite was advertising his professional services, which included “Developing and printing for amateurs. Views, Groups, Interiors and Haciendas; also Flash Light Photos at night.” Waite certainly traveled widely throughout Mexico, taking photographs and undertaking commissions related to archaeology, scenery, tourism, and indigenous groups. By February 1900 he had amassed “a great variety of general views comprising more than 1000 subjects from all parts of the Republic.” On a short business trip to the U.S. that month, Waite personally delivered hundreds of 20x 24-inch prints of the Mexican National Railway to investors north of the border.

During the winter of 1900-01, Waite spent several weeks in southern Mexico, on a commission from the U.S.-owned Chiapas Rubber Company to document its operations, including land clearance, planting, rubber tree cultivation and tapping; these photos were intended to stimulate further foreign investment in the company and its activities. Waite also documented the cultivation and harvesting of coffee, cacao, tobacco and sugar cane.

These photo trips were not without their dangers. The Mexican Herald informed readers in early 1901 that, a few weeks earlier (during his Chiapas trip), Waite had suffered an accident while taking his photographic equipment up the Río Michol, and barely escaped with his life. The boat capsized and Waite and his boatman were thrown into the torrent. As they struggled to the shore, they managed to salvage a can of crackers and a valise which fortuitously contained a flask of cognac.

The disaster cost Waite his ‘small’ (6 ½ x8-inch format) camera in the raging waters, and he was left with only his ‘large’ (20×24-inch format) Rochester Optical camera, which weighed 100 kg in its traveling case. Undaunted, Waite carried on. At Palenque, it took a team of 12 local helpers an entire day to carry the camera the six miles (km) from the village to the ruins, where Waite then took 24 photos of the archaeological site, but only after his 12-man crew had spent eight days hacking down enough brush and foliage to guarantee the best views. Waite’s photos of Palenque were one of the highlights on Mexico’s stand at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, that year.

That boat accident was not the only calamity to befall Waite in 1901. A few months later, he had an unexpected brush with Mexican police, accused of sending “indecent” material through the mail. A note in El Imparcial reported that one shipment from Waite contained photos of “miserable hovels” and “disheveled dirty women dressed in rags and men degenerated by every vice imaginable”. It was not impounded, but postcards in a second package showing “two dirty, absolutely wretched boys wracked with disease” were, and led to Waite’s arrest. Waite paid $400 pesos and was released from Belén prison three days later. Waite’s offense was not taking risqué “portraits of pubescent children” (for which Winfield Scott had been briefly imprisoned in California) but depicting the underbelly of Mexican society, which local authorities hoped would remain invisible to tourists.

Things brightened up in July 1901 when Waite was asked to visit Iguala, Guerrero, for a seance. Waite told a reporter afterwards that his photographic plates would convert skeptics: “I never had any faith in the spiritualist doctrine, but the appearance of scenes on the plates of my camera which I knew to have been absolutely clear… has aroused the curiosity of not only myself but many others who were previously skeptical on the subject.”

Waite’s major commissions that year included several for the government: Waite was tasked with producing about 1500 large format views of archaeological ruins in the republic for displays in the national museum, the precursor of Mexico’s world famous Museo Nacional de Antropología. And he was also hired by the government to supply photographs, including a series relating to bullfighting, for use on Mexico’s stand at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

Waite was back in the U.S. in 1902, “on business connected with his mining interests in Mexico. During the course of his travels through the interior as a landscape photographer, Mr Waite has secured control of a number of properties and the object of his visit to the U.S. is to place his property before American capitalists.” These mines were probably the small gold, silver and lead mines in Taxco, which he registered in his name in 1904. Not much more is known about them, so presumably they were never very successful.

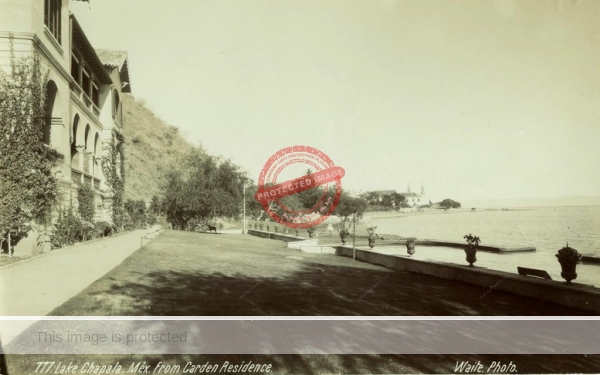

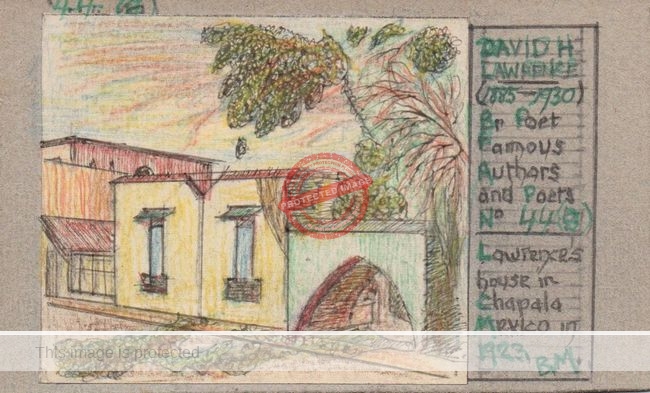

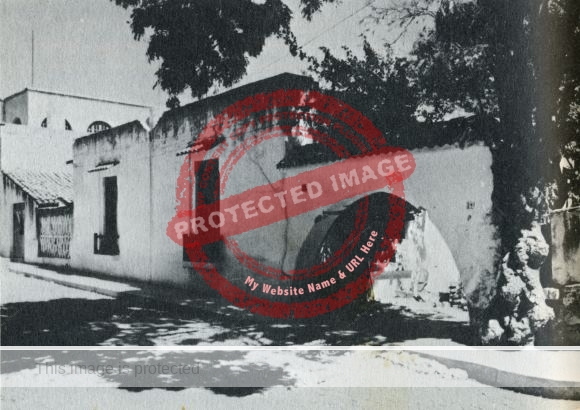

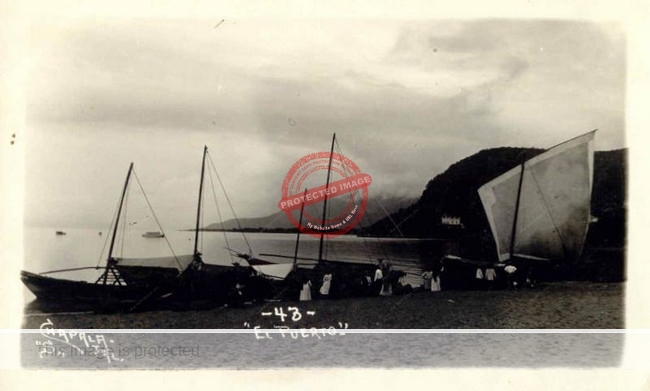

C.B. Waite. c 1898? Lake Chapala from Carden Residence (Villa Tlalocan), Chapala.

A few months after purchasing the photographic view business of Cox and Carmichael in 1904, Waite visited Atequiza hacienda, then owned by the Cuesta Gallardo family. From a photographic standpoint, this was a significant event, since it was here, eight years earlier, where French cinematographer Gabriel Veyre and his partner Claude Ferdinand Von Bernard filmed eight short movie films, some of the earliest movies shot anywhere in Mexico, depicting rural life, dances, cockfights and daily activities. Atequiza hacienda was also the birthplace of Octaviano de la Mora (1841-1921), arguably the most famous of all the early photographers based in Guadalajara.

Waite has left us several very interesting photographs of the hacienda, including views of the chapel, the hacienda store and main patio, the view of the main buildings from the mill, and a panoramic view of the hacienda in its idyllic setting. A year after being the official photographer documenting U.S. Secretary of State Elhu Root’s visit to Mexico in 1907, Waite revisited Atequiza to take photographs of the “La Florida” mansion and of hacienda’s orange groves.

Though Waite certainly participated as official photographer on several academic expeditions, I do not believe they include the two in 1908—led respectively by Norwegian anthropologist Carl Lumholtz and German ornithologist Hans Gadow—claimed in the timeline offered by Fuentes Rojas and her colleagues. First, there is no record of Lumholtz (author of Unknown Mexico, based on his first four trips to Mexico, all prior to 1900) visiting Mexico in 1908. And, secondly, Waite is never mentioned in Gadow’s 1908 book “Through Southern Mexico.” The confusion in the latter case perhaps arose because Gadow dedicated his book, “To C.B.”, but this is not a reference to C.B. Waite, but to pioneering American ornithologist Charles Beebe.

By 1910, Waite was a highly respected member of Mexico City’s foreign community and master of the Freemasons’ Toltec Lodge. Though Waite’s photographic activities were greatly reduced after the downfall of President Díaz, and the start of the revolution, he is known to have photographed Mexico’s centenary celebrations in 1910 and to have taken some photos related to the Maderista conspiracy.

Despite what some websites claim (eg. Getty Research Institute), there is no evidence that Waite left Mexico for the U.S. in 1913. On the contrary, Waite and his wife continued to live in Mexico City for the next decade, as is evidenced by his passport applications in 1918 and 1920.

His 1918 passport application included a lengthy affidavit explaining why he had lived outside the U.S. since May 1897:

“My mother died of consumption when I was four years old. My health failed when I was a young man and it was believed that I would die of consumption also and I was ordered to live in a warm climate by my physicians and came to Mexico where I established a Commercial Photography business, making a specialty of wholesale views of the country on a large scale. Illustrations for books and magazines of the interesting features of the country was an important part of my business.”

In the same application, Waite listed his visits to the U.S. since moving to Mexico: September 1898, January 1899, July 1899, February 190l, May 1902, July 1903, September 1903, December 1904, December 1906 and January 1912.

It was only after Alice’s death in the American Hospital in Mexico City in June 1923 that Waite opted to return to the U.S. to be closer to his daughter. He revisited Mexico with his daughter briefly in 1925, before dying in Los Angeles at the age of 65 on 22 March 1927.

Waite’s body of work

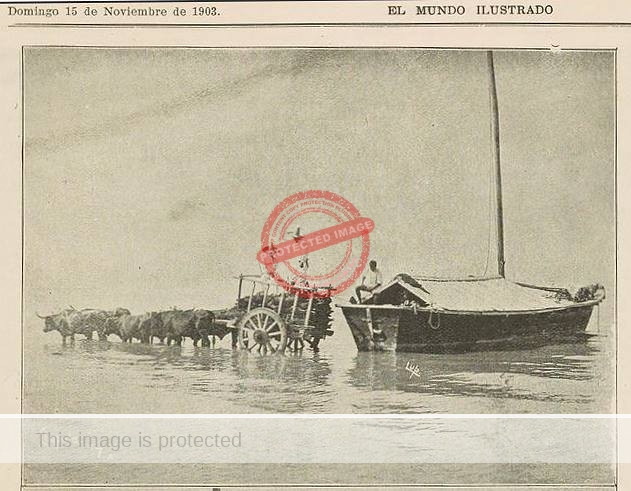

Landscapes, markets, railway lines, towns, people going about everyday tasks, farms, tropical crops, rural areas, fiestas in danger of extinction, major cities, bull fights, official events… Waite photographed all these and more, amassing a huge collection of images, which were widely published, including in the popular periodical El Mundo (later El Mundo Ilustrado), Modern Mexico, and as postcards issued by almost all the larger postcard publishers.

As early as 1901 the Sonora News Company was advertising that it sold “Waite’s Photographic Views” of “Native Types and Scenes.” This series included costumbrista images of men, women and children going about their everyday occupations and tasks. In 1902, Granat’s Mexican Specialty Store offered “Waite’s, Carmichel’s [sic] and Other Photographers’ Views of Mexico” for $2.25 a dozen.” Waite’s photos were also published and/or sold by Ruhland & Ahlschier; Latapi y Bert; J. G. Hatton; and Jacob Kalb of the Iturbide Curio Shop (all based in Mexico City), and Juan Kaiser, based in Guadalajara.

Waite’s photos were used to illustrate numerous books, including ornithologist Charles Beebe’s Two Bird-Lovers in Mexico (1905) and Percy F. Martin’s Mexico of the twentieth century (1907).

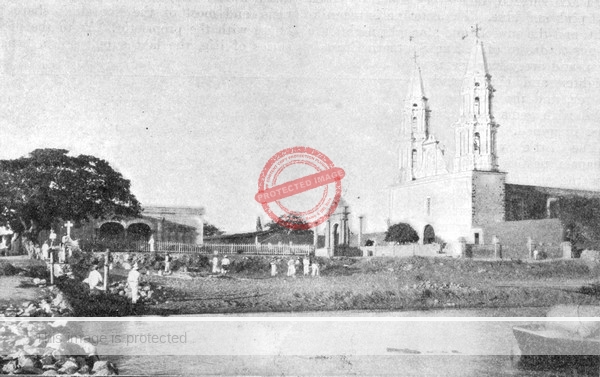

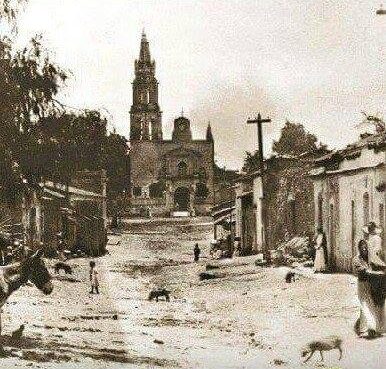

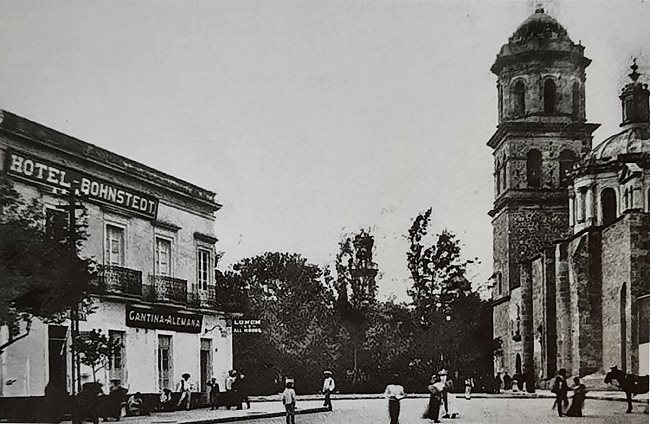

Waite. Church at Chapala, as published in Pauncefote, 1900.

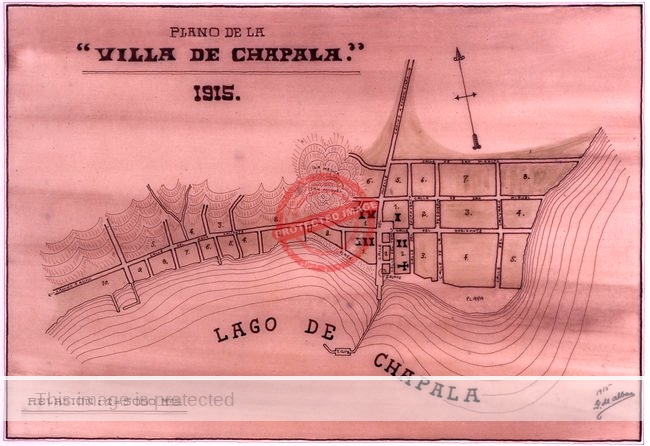

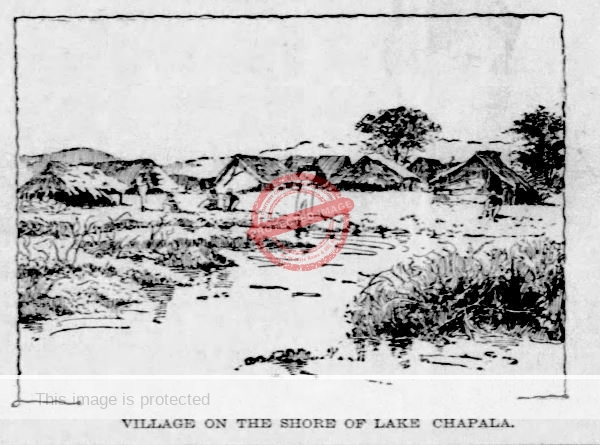

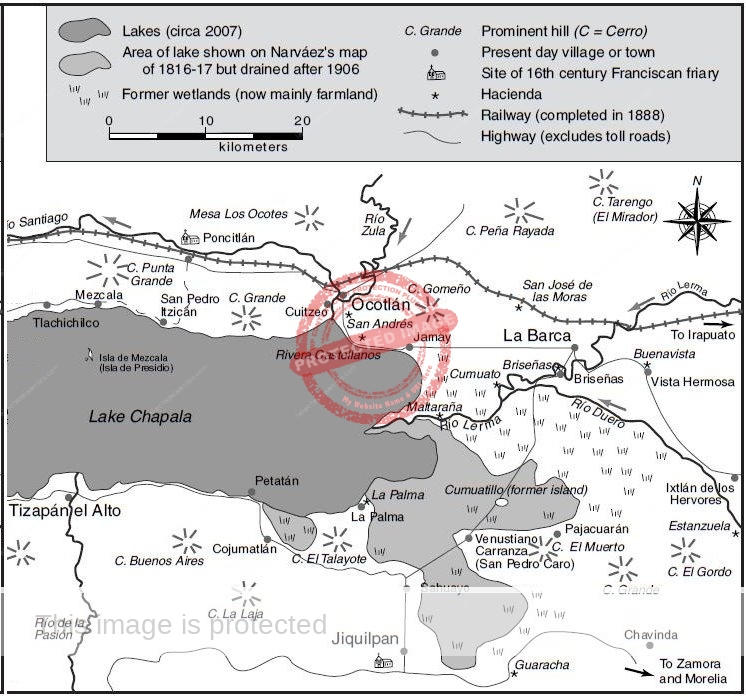

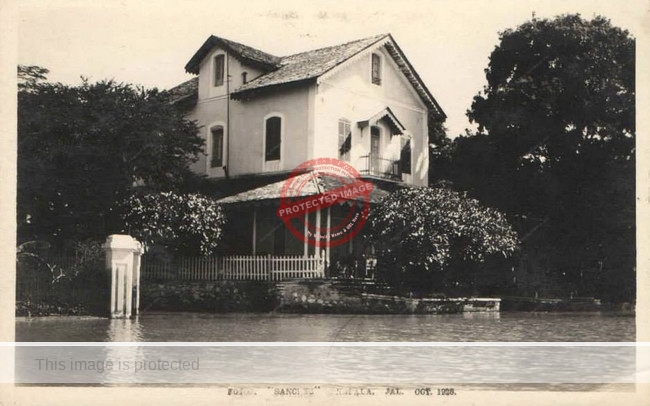

In 1905, Waite applied for, and was granted, formal registration for ten photographs related to Lake Chapala, numbered 770-779. They included two photos of “the Carden residence” (Villa Tlalocan), built by British consul Lionel Carden in 1896. Three years later, Carden sold the property and moved to Cuba, so these two photos—and most probably the other eight—must be much earlier than 1905, and were probably taken at the end of the 1890s. Waite’s other photographs of Chapala in this group of ten, some of them published as postcards, included “Street in Chapala” “Cathedral, Chapala,” and “La Playa, Chapala.” Several of the photos, including the one of San Francisco Church (above) were first published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1900 to illustrate the Hon. Maud Pauncefote’s landmark article about Lake Chapala. (An extended excerpt of the article appears in chapter 46 of Lake Chapala Through the Ages.)

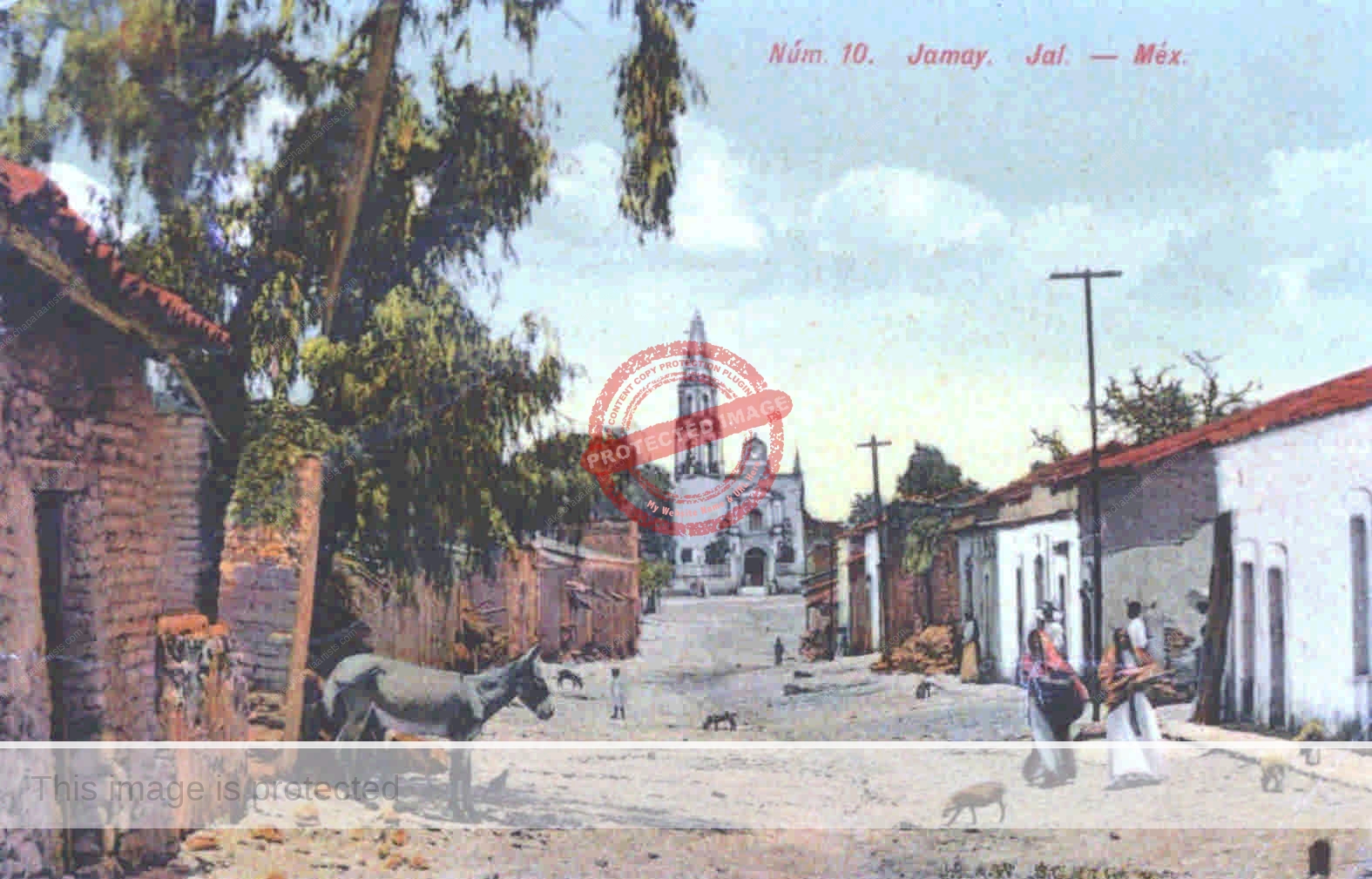

Waite later also registered a large number of images acquired from other photographers such as Winfield Scott, including many additional images of Chapala, as well as images of Prison Island (#2094), Tuxcueca (2177), Tizapan River (2182), Point Fuerte, Chapala (2196), Jamay (2840), Petetan (sic, 3056), Alacran Island (3058) and Cojumatlan (3062). It is likely that some or all of these were photographs taken by Scott.Examples of Waite’s work have found their way into numerous major U.S. museum and library collections, including The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens; University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research; Princeton University Library’s Collections of Western Americana; the Latin American Library of Tulane University; the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin; the Eugene P. Lyle, Jr. Photographs, University of Oregon; the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University; and at the Tomás Rivera Library at University of California, Riverside.

Despite this, there have been relatively few exhibitions featuring his work apart from “Mexican Life and Culture During the Porfiriato: The Photography of C.B. Waite, 1898-1913″ at the Southwest Museum, Los Angeles, in 1991; “Mexico: From Empire to Revolution” at the Getty Institute in 2000-2001; and “Charles B. Waite. Primeras impresiones” at Galerías de la Antigua Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City in 2016.

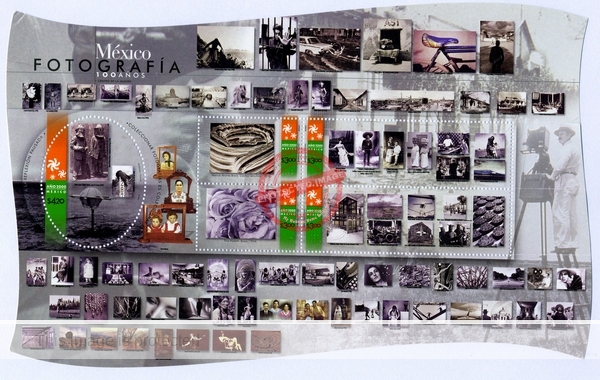

Waite’s significant contribution to the history of photography in Mexico was recognized at the turn of the millennium by the nation’s postal authorities, when it issued a series of stamps and souvenir sheet to commemorate 100 years of photography in Mexico. A number of the stamps incorporated tiny versions of photographs taken by Waite into their design.

Servicio Postal Mexicano. (2000) 100 years of photography.

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Several chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village offer more details about the history of the artistic community at Lake Chapala.

Sources

- Francisco Ballesteros Montellano. 1989. “C. B. Waite, profesional fotógrafo.” Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- ___ 1994. C. B. Waite, fotógrafo. Una mirada diversa sobre el México de principios del siglo XX. Mexico: Grijalba/CNCA.

- ___ 1998. Charles B. Waite: la época de oro de las postales en México. Mexico: CONACULTA (Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y Las Artes).

- Francisco Hernández. 2018. Diario sin fechas de Charles B. Waite (novel). USA: Almadia.

- Benigno Casas. 2010. “Charles B. Waite y Winfield Scott: lo documental y lo estético en su obra fotográfica”. Dimensión antropológica, 48: 221–244.

- Elizabeth Fuentes Rojas, Gabriela Prieto Soriano, Gabriela Vilches Larrea (coordinators). 2016. Charles B. Waite. Primeras impresiones. Mexico City: UNAM, Facultad de Artes y Diseño.

- Rosa Casanova and Adriana Konzevik. 2007. Mexico: A Photographic History. Mexico: Editorial RM.

- Clarence Alan McGrew. 1922. City of San Diego and San Diego County. The Birthplace of California. The American Historical Society. Vol I, p 289.

- Hon. Maud Pauncefote. 1900. “Chapala the Beautiful.” Harper’s Bazar, Volume XXXIII #52, December 29, 1900. p 2231-3.

- The Mexican Herald: 29 Aug 1897; 21 Feb 1900, 5; 18 Nov 1900, 6; 10 Feb 1901, 8; 30 March 1901, 8; 14 July 1901, 17; 28 July, 1901, 17; 19 Aug 1901, 8; 17 April 1902, 8; 18 Nov 1902; 3 March 1904, 7; 1 Sep 1904, 11; 24 Apr 1908; 27 June 1910; 18 August 1914, 5.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación: 19 Jan 1905, 277-278-279; 17 March 1905, 300; 6 April 1905, 663; 13 April 1905; 14 Jan 1908, 150-151; 1 June 1908, 477-8; 14 July 1908, 202-3; 5 Oct 1908, 493.

- The Two Republics: 5 Jan 1898, 6.

- El Imparcial: 5 June 1901.

- Jalisco Times: 10 Apr 1908.

- El Universal, 20 May 1925.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.

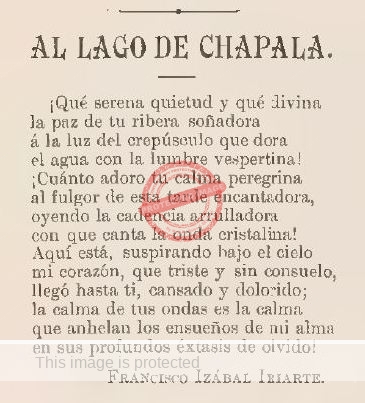

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

Izábal, who never married, was exceptionally well connected and a member of numerous civic and political committees and groups. He was a prominent leader of the Sinaloan community in Guadalajara, and led fund-raising efforts whenever his native state suffered from storms, disease or earthquakes. In 1897, he was one of the small group accompanying General Cañedo, then Governor of Sinaloa, on a business trip to Mexico City.

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.

Dollero was born in Turin in November 1872. He moved to Mexico in 1895, but continued to make regular return trips to Europe. In 1898, he married Maria Luisa Paoletti, countess of Rodoretto (the daughter of the Italian vice consul to Mexico) in Mexico City. Eight years later, in 1906, the couple—now with two children, Ernastina and Lamberto, and a Mexican servant—are named on the passenger manifest of a boat back from Europe. The couple added twin boys to their family in 1912.