Despite not being a native of Chapala, Guillermo de Alba (1874–1935) left a diverse and rich legacy in the city. De Alba was born in Mexico City. After his family moved to Guadalajara, de Alba attended the Escuela Libre de Ingenieros, from which he graduated as an Ingeniero Topógrafo (engineer-surveyor) in 1895. [At that time the school did not offer any professional qualification as an architect.]

It is evident from the accounts of de Alba’s grandson—Martín Casillas, a prominent author and novelist, who has published several works relating to his grandfather—that, after graduating, Guillermo de Alba spent some time in Chicago where he was influenced by the Chicago School of architecture. (The Chicago School was a style or movement, not an institution.) In Chicago, de Alba likely studied recently completed buildings, and perhaps met the two most famous proponents of the Chicago school: Dankmar Adler and Louis H. Sullivan (‘form follows function’), who had dissolved their own architectural partnership in 1894, a year or two before de Alba’s visit.

By 1898, de Alba, still in his early twenties, was living in Chapala and working in construction with Manuel Henríquez. De Alba married Maclovia de Cañedo y González de Hermosillo (1859-1933) in Chapala in 1900, and their only child, Guillermina, was born two years later.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, de Alba designed and built numerous fine residences and commercial buildings in Guadalajara and Chapala, before moving to live in Mexico City in 1926.

His works in Guadalajara included the Hotel Fenix, Casa Abanicos and Villa Guillermina, but the most dramatic of all, in terms of impact on the city, was the major project to develop Colonia Moderna, a new ‘garden city’ neighborhood.

Villa Cristina (1903)

At Lake Chapala, de Alba’s earliest large project was to design a country residence, originally named Villa Cristina, at the eastern end of the lake near Hacienda Cumuato, for José G. Castellanos and his wife, Cristina, in 1903. This building was later acquired by Joaquín Cuesta Gallardo and his wife, Antonia Moreno Corcuera. After decades in ruins, efforts are now apparently underway to restore the property, commonly known as Hacienda Maltaraña.

Not long afterwards, De Alba was asked by Ignacio Arzapalo to design a major hotel in the then small settlement of Chapala. Arzapalo already owned the Hotel Arzapalo, the area’s earliest purpose-built hotel, which opened in 1898, and had realized that Chapala needed another large hotel if it was to satisfy the growing demand for rooms. The de Alba-designed Hotel Palmera was completed in 1907. De Alba’s other works in Chapala include Mi Pullman (1908), a remodeling of Villa Ave María (1919), Villa Niza (1919), and the Chapala Railroad Station (1920).

Hotel Palmera (1907)

Hotel Palmera, c. 1908. Photo: Calpini.

The 60-room Hotel Palmera, built at a cost of $100,000, was completed in 1907, and opened the following year. It was described at the time as a “modern construction, brick, iron and cement”, with “fine woodwork,” “American furnishings, electric bells” and a “dining room for 400 people.” Following a change of ownership in the 1920s, the building was divided into two independent hotels. The southern wing, purchased by Ramón Nido and his Mexican wife, Sara, reopened in 1930 as the Hotel Nido. In 2001, this wonderful old building was repurposed as the town’s Palacio Municipal. The building’s stairwell has a magnificent 240-square-meter mural by talented and energetic Ajijic artist Efrén González depicting local history.

Mi Pullman (1908)

Mi Pullman, 2019. Photo: Tony Burton

Built on an unusually narrow lot, Mi Pullman, at Aquiles Serdán #28, is one of the most distinctive private residences in Chapala. This tall, skinny building, inspired by a Pullman rail car, was built as de Alba’s family home. Its construction, which began in 1907, was completed in June 1908. The house-warming party for the completed residence was a grand formally attired affair, as was to be expected given the owner’s growing reputation as an architect.

By the 1990s (and several owners later) the building had fallen into a terrible state of repair, before its potential was recognized by English-born Rosalind Chenery. Chenery eventually purchased the building, and restored this intriguing narrow Art Nouveau townhouse to its former glory, inside and out. It retains many original fixtures and fittings, including oak wood parquet flooring, stained glass windows, tile floors and a cast iron bath tub. Chenery’s multi-part account of her extraordinary achievement can be read on MexConnect, starting with Mi Pullman: remodeling a Mexican Art Nouveau townhouse.

Pier (1908)

In 1908, Guillermo de Alba was entrusted with adding steps to the east side of Chapala pier (which had been completed a decade earlier), and with some renovations to its surrounds.

Calle Lourdes (1909)

Guillermo de Alba was commissioned in 1909 by Aurelio González Hermosillo, the owner of Villa Montecarlo, to lay out a new street, lined with palm trees, named La Calzada de las Palmas. On the final day of that year, the street was the scene of a hill-climbing contest for automobiles. The vehicle which made it all the way to the top, and won the competition, was a German-made Protos with five passengers driven by Benjamín Hurtado. The short street is known today as Calle Lourdes.

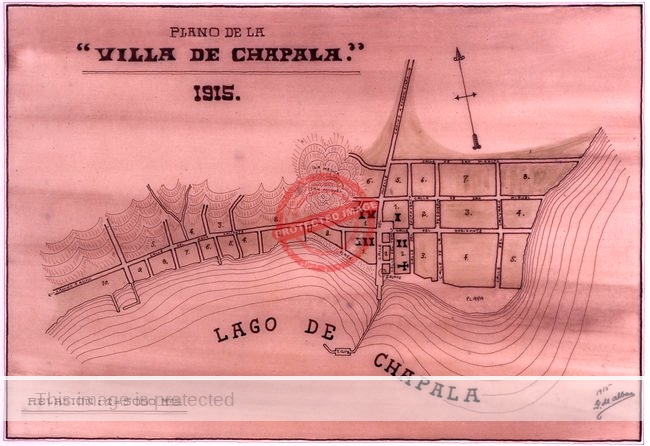

Street plan of Chapala (1915)

Guillermo de Alba’s 1915 street plan of Chapala. (Chapala archives)

We are indebted to de Alba for the earliest known street plan of Chapala, dating from 1915. This is an immensely valuable historical document, indicating the then limits of the small but growing settlement.

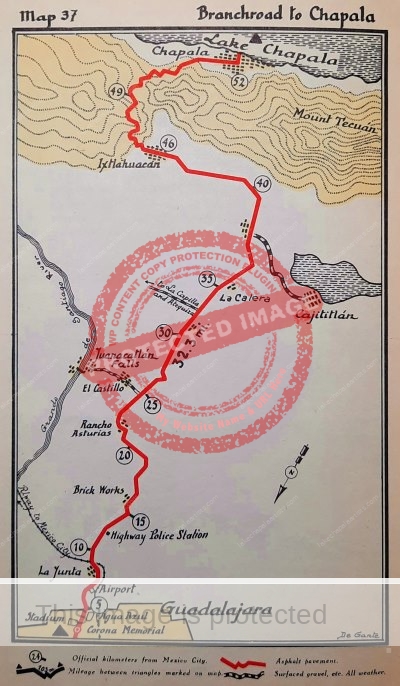

Automobile road (1916)

When fund raising began in 1916 to build a new automobile road between Guadalajara and Chapala, de Alba was elected the group’s treasurer. Several prominent individuals each gave $5000 to supplement a state government grant of $23,300. The new road made it much easier for wealthy families to visit Chapala, even if only for a day, or over a weekend.

Photography and Chapala’s first tennis court (1918)

Guillermo de Alba. 1918. Tennis match, Chapala. (Aquellos tiempos en Chapala)

The lakefront restaurants immediately west of the Beer Garden in Chapala occupy property that was once used for the area’s earliest lawn tennis courts. They were laid out by Guillermo de Alba in 1918, just after the end of the first world war, and financed by Ramón Castañeda y Castañeda, whose daughter, Margarita, had learned to play tennis “at one of the best schools in England” and was one of the top players in Guadalajara.

Besides his work as an engineer-architect, de Alba was also an excellent photographer. We are indebted to him for some fine pictures of Chapala dating from the early years of the twentieth century.

In 1920, Guillermo de Alba helped a fellow photographer—José Edmundo Sánchez—open Pavilion Monterrey, a beachfront bar where food and drinks were served in an open-air pavilion, located mid-way between the Hotel Arzapalo (the Beer Garden today) and the Braniff mansion (Cazadores restaurant).

Villa Ave María (1919)

Villa Ave María, 1919. Photo: Guillermo de Alba

At Aquiles Serdán #27, across the street from Mi Pullman, is Villa Ave María. It is believed that Guillermo de Alba remodeled an existing building on this site in 1919 to create the stately villa shown in the image. Ninety years later, following many modifications, this building was registered as a three-unit condominium.

Villa Niza (1919)

Villa Niza, c. 1920. Photo: José Edmundo Sánchez

Villa Niza, at Hidalgo #250, was designed by Guillermo de Alba for Guadalajara businessman Andrés Somellera. Completed in 1919, the house makes the most of its lakeshore position with a mirador (look out) atop its central tower offering sweeping panoramic views over the gardens and lake. De Alba’s strong geometric design boasts only minimal exterior ornamentation. Villa Niza has been well maintained over the years and retains many of its original interior features.

Villa Paz (1920)

Villa Paz, 1920. Photo: Guillermo de Alba

Though definitive evidence is lacking, this photograph taken by Guillermo de Alba suggests that he may have remodeled Villa Paz (at Hidalgo 234) in 1920. The villa, originally known as Casa Paulsen, was owned at the time by Ignacio E Castellanos and his wife, Paz González Rivas. De Alba had previously designed Villa Cristina (1903) for another member of the Castellanos family. Villa Paz was restored and opened as a boutique hotel in 2017.

Chapala Railroad Station (1920), now the Centro Cultural González Gallo

Centro Cultural González Gallo (former Chapala Railroad Station), 2019. Photo: Tony Burton

The crowning glory of Guillermo de Alba’s architectural career in Chapala was the elegant and imposing former Chapala Railroad Station, now the Centro Cultural González Gallo. Work on this building began in 1918, commissioned by visionary Norwegian entrepreneur Christian Schjetnan as the terminus for the La Capilla-Chapala railroad, and was completed in 1920. While Schjetnan envisioned that this grand station terminus would be a focal point for a major hotel, magnificent park and scores of beautiful residences—a breathtakingly ambitious idea—the rest of the project never made it beyond the drawing board. The railroad closed in 1926 and the station building eventually fell into disuse. Restoration of the historic building began in 1998, and it was reopened as a Cultural Center in 2006. It retains some original flooring and architectural details, though tall glass panels were added to protect the formerly open station vestibule from any adverse weather.

Cerro de San Miguel (1930s)

After moving from Chapala to Mexico City in 1926, de Alba worked as a draftsman in the Secretaría de Recursos Hidráulicos drawing designs for bridges and dams. He retained a keen interest in Chapala, and was asked in 1931 by the town’s then mayor, Basulto Limón, to design a walkway to the top of Cerro San Miguel with shelters and pergolas near the top to serve the needs of visitors who climbed the hill for the panoramic view. Sadly, this plan was apparently never carried out.

Did Guillermo de Alba design the Hotel Arzapalo (1898)?

Though the design of the Hotel Arzapalo, which opened in 1898, has sometimes been attributed to Guillermo de Alba (including in a display honoring de Alba in the Centro Cultural González Gallo), his name does not feature in any of the contemporaneous accounts of the hotel’s construction or opening celebration. For this reason—and others detailed in If Walls Could Talk—I do not believe that de Alba designed the Hotel Arzapalo, though it is possible that he helped with its construction. The claim may have arisen from a misreading of this (admittedly ambiguous) sentence on page 116 of Antonio de Alba‘s Chapala: “A los 7 años, habiendo progresado la empresa, edifice el mismo Sr. Arzapalo, bajo la dirección del Ing. Guillermo de Alba otro hotel, el ‘Hotel Palmera.'” (“After 7 years, the business having progressed, the same Mr Arzapalo built, under the direction of Engineer Guillermo de Alba another hotel, the ‘Hotel Palmera.'”)

Regardless of who designed the Hotel Arzapalo, Guillermo de Alba made an incomparable contribution to Chapala’s history and heritage, bequeathing us several superb buildings which have not only withstood the test of time but which are still worthy of our admiration more than a century after they were first built.

Note: More details of these projects can be found in If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants, translated into Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes. My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how the small village of Chapala morphed into an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources

- El Informador: 17 Oct 1918, 1.

- J. Jesús González Gortázar. 1992. Aquellos tiempos en Chapala. Guadalajara: Editorial Agata.

- Jaime Álvarez del Castillo (coordinator). 2002. Arquitecto Guillermo de Alba. Editorial Agata / Fotoglobo.

- María Dolores Traslaviña García. 2006. Guillermo de Alba. Gobierno de Jalisco Secretaría de Cultura.

- Brigitte Boehm Schoendube (coord.), Cartografía Histórica del Lago de Chapala.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.