As explained in a previous post, my on-going fascination with the history of Lake Chapala was stimulated, in part, by the chance discovery many years ago of a copy of Antonio de Alba‘s 1954 book, Chapala.

The online claim (made only a few years ago) that Chapala is “the most accurate book to date about the local history” may have been true many decades ago, but has certainly not been true since the turn of this century.

The focus of my personal interest has been on when, how and why Chapala first became a center for international tourists. The ‘when’ is the easy part, given that the town’s first major hotel, the Hotel Arzapalo, opened its doors in 1898. The ‘how’ and ‘why’ are trickier to answer, and have led me down innumerable ‘rabbit holes’ related to the lives of early foreign settlers in Chapala.

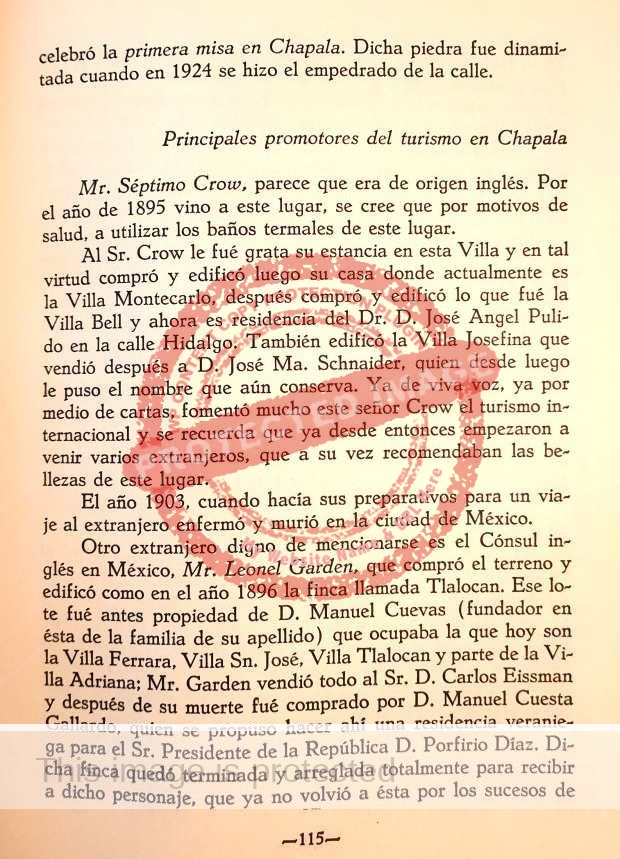

What has emerged from years of research, and new online friendships with the descendants of many of these early settlers, is that the story of Lake Chapala is far more complex (and interesting) than I had ever imagined. Many of the details in de Alba’s account of the “principal promoters of tourism in Chapala” (page 115) need to be reconsidered, and in some cases rejected.

Please note that I am not, by publishing this critique, trying to disparage or discredit Antonio de Alba, his research or his book. On the contrary, it was his book that got me started down this road! But, like all accounts of history, over time new facts come to light, alternative interpretations are proposed—some of which become accepted—and a new, revised (and hopefully more accurate) version of the story is developed.

Let’s take a close look at de Alba’s account of the principal promoters of tourism in Chapala. It did not take me long to realize that ‘Séptimo Crow’ was Septimus Crowe (with an ‘e’ at the end), who was, as de Alba stated, of English origin, though he was actually born in northern Norway, where his father had a massive copper mine. It took me a lot longer to realize that the “Mr. Leonel Garden,” who built Villa Tlalocan, was Mr (later Sir) Lionel Carden (with a ‘C’), and even longer before I identified ‘Sr. D. Carlos Eissman” as Karl (Carlos) Eisenmann. Once I had their real names, it was relatively easy to find out a lot more about these individuals and their lives, and their connections to Chapala.

It turned out that Septimus Crowe, for example, had abandoned his wife and young son in Europe when he moved to Mexico. His son was informed that his father had died, and never lived to learn the truth; members of the succeeding generation were totally astonished to find a brief reference in one of my articles about Septimus’ life in Mexico.

De Alba writes that Crowe arrived in about 1895. While I can’t prove precisely when the eccentric Mr Crowe first came to Chapala, it was certainly several years earlier than that, as I have pointed out repeatedly over the past two decades. This is known because there is a clear reference to Crowe by Mexican diplomat-author Eduardo A. Gibbon in a book published in 1893. Gibbon’s account refers both to Crowe having built a “very lovely estate that can be seen from the lake on a hill, a quarter of a league from the village of Chapala” (now the site of Hotel Montecarlo) and to Crowe having “stimulated others to build holiday homes and with them give life and civilization to this very beautiful region.”

In the past several years, as I delved ever deeper into the lives of Crowe and others, I have been able to prove that Crowe built all the three houses mentioned by de Alba (Villa Montecarlo, ‘Villa Bell’ (Villa Bela), Villa Josefina), though not in the order he suggested. Before he built Villa Bela, Crowe had built Casa Albión, renamed Villa Josefina after it was bought by American-born beer magnate Joseph Maximilian Schnaider.

In the case of Villa Tlalocan, de Alba is correct that the house was built in about 1896: construction began in 1895 and the Cardens were able to move in the following year, in time to invite President Díaz for breakfast one morning in early November. De Alba is also correct that Carden sold Villa Tlalocan to Carlos Eisenmann. However, de Alba’s claims that the house was then bought by Manuel Cuesta Gallardo ‘after Eisenmann’s death’, and that the new owner built a home there intended as a gift for President Díaz, which the President never received because the Mexican Revolution broke out (1910), are inaccurate.

First, I have never found any contemporaneous newspaper accounts supporting the idea that Manuel Cuesta Gallardo built any home intended for President Díaz. There are, though, several references to a home being prepared for the President by his inlaws at El Manglar. Secondly, Eisenmann died in 1920 (in Germany), three years after Manuel Cuesta Gallardo had already transferred the title of Villa Tlalocan to a younger sister.

I repeat—for those who have read this far—that none of this post is intended in any way to disparage Antonio de Alba, his research or his book. It was my chance find of Chapala back in the 1980s that led me to become so passionate about exploring the history of how the small fishing village of Chapala became such an important international tourist destination.

Reading the book

Copies of Chapala, which has never been reprinted, are difficult to find. Fortunately for readers, Javier Raygoza Munguía, the publisher of the weekly PÁGINA Que sí se lee! has uploaded the entire text as a series of digital files which can be accessed via the link.

Several chapters of If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants – available in Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes – offer more details about the history of Chapala.

Sources and references

- Antonio de Alba. 1954. Chapala. Guadalajara: Banco Industrial de Jalisco.

- Eduardo A Gibbon. 1893. Guadalajara, (La Florencia Mexicana). El salto de Juanacatlán y El Mar Chapálico. 1992 reprint Guadalajara: Presidencia Municipal de Guadalajara.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).