With the exception of Bernardo de Balbuena’s mention of Chapala in his epic poem “El Bernardo,” (written between 1592 and 1602 and published in Madrid in 1624), one of the earliest literary mentions of Lake Chapala is in a story by Andrew Grayson published in 1870. Grayson, an ornithologist, rarely wrote fictional pieces and is far better known for his non-fiction natural history articles, published in numerous US magazines and newspapers in the first half of the nineteenth century.

William Jewett. 1850. Portrait of Andrew and Frances Grayson, and their son, in California. (Terra Foundation for American Art).

In “Ixotle,” posthumously published, the author made good use of his knowledge of Western Mexico, and describes how he is making “collections of Ornithology” when he encounters an elderly local priest who turns out to have an extensive knowledge of the birds of Western Mexico. The priest recounts a local legend explaining why the Tres Marias islands, a birding hotspot, were never settled. The legend revolves around the God of the Storms of the Sea, Tlaxicoltetl, and a beautiful, intelligent 16-year-old girl, Ixotle (“blooming flower”), who has been chosen by her people to be sacrificed to their ancient gods. The girl refuses and prophesies that:

a people with white faces and long, red beards are coming — they are already on the march. They carry in their hands the lightning and the thunder, with which they will demolish your great temples. They are sent by the true God. Not a stone will be left; and on their sites will be erected white temples—the pure temples of the true and only God. Beware, then, and let this be the last of human sacrifice!”

One short section of the story relates directly to Lake Chapala:

From this locality [San Blas] a large, well-beaten trail extended through Tepic on to where Guadalajara now stands, and where then stood a large city, which was called Chapala.

The lake near Guadalajara is still known by that name; and the Indians found near its borders, who yet live in a semi-barbarous state, are called to this day Chapalo Indians, and are a very degraded, thieving race. But previous to the conquest, they were a numerous and industrious people—well skilled in the manufacture of articles of utility. Cotton cloths, both coarse and fine, were largely manufactured by them, as also various kinds of pottery; and their dressed deer-skins were of a superior quality. These kinds of goods were bartered with the Tepic Indians for fish, pearls, etc.

Their principal town was where the beautiful city of Guadalajara now lifts its numerous church-spires proudly over the once heathen temples of human sacrifice. It was then a large city, and continues to be second only to the Capital.”

Click here for the full text of “Ixotle.”

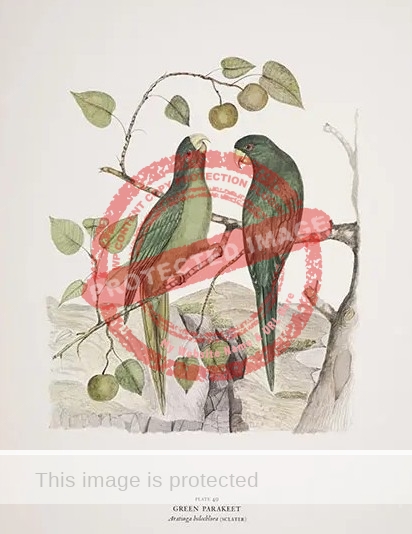

Andrew Grayson. Green Parakeet (a Mexican endemic). Image believed to be in public domain.

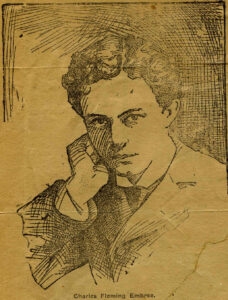

Andrew Jackson Grayson was born in Louisiana in 1819 and died in Mazatlan in 1869. A sickly child, he spent most of his childhood roaming the countryside, watching and drawing local birds and other wildlife. As an adult, after failing to run a store profitably in Louisiana, he married Frances Jane Timmons in 1842 and two years later the couple moved to St. Louis, in preparation for the overland trek west to California. They arrived in California in October 1846, where Grayson bought several lots in San Francisco and the surrounding area.

Seeing an exhibition of bird paintings by James John Audubon in San Francisco in 1853 reignited Grayson’s childhood passion for drawing birds. Grayson became a self-taught painter and taxidermist, working first in San Jose, then Tehuantepec, Mexico (1857), and the Napa Valley (1859) before moving to Mazatlán where he owned a general store and began working towards a book he envisaged titled “Birds of the Pacific Slope.”

Grayson spent the next decade submitting articles, mostly about natural history, to a number of newspapers and magazines in California and Mexico. He also supplied the Smithsonian Institution with birds and bird biographies. Despite making exhaustive efforts to find a sponsor for his book on Pacific Slope birds, the work remained unfinished when Grayson died of “coast fever” in Mazatlán in 1869. Shortly after, his wife returned to California, where she later remarried.

156 of Grayson’s stunning bird paintings were eventually published in a collectors’ edition by Arion Press in 1986, accompanied by a detailed biography of the ornithologist-artist.

An archive of Andrew Jackson Grayson papers and paintings is held by The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Sources

- Andrew J. Grayson. 1870. “Ixotle.” Overland Monthly, vol. V, #3, (Sept 1870), 258-261.

- Anon. Guide to the Andrew Jackson Grayson Papers, 1844-1901. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- Robert J. Chandler. 2011.”Andrew Jackson Grayson: The Birdman was a traitor.” The California Territorial Quarterly. #88 (Winter 2011), 46-51.

- Lois Chambers Stone. 1986. Andrew Jackson Grayson: Birds of the Pacific Slope: A Biography of the Artist and Naturalist, 1818-1869. Arion Press.

Several chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village offer more details about the history of the literary community in Ajijic.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.