Author, playwright and flying ace Elliot William Chess was in his late-forties when he spent several months in Ajijic at the small hotel Casa Heuer in 1946, but had already experienced far more than most people can manage in twice as many years.

Born in El Paso, Texas, at the turn of the century, Chess left El Paso High School when the first world war broke out and emigrated to Toronto, Canada, to enlist in the Royal Flying Corps. His RFC papers give his birth date as 25 Oct 1898, though it is entirely possible that the teenage Chess inflated his age by a year or two to boost his chances of acceptance.

He served overseas from age 18. After the end of the war (1918) he was the youngest American pilot to join the Kosciusko Squadron in Poland. He fought with them for two years in the Polish-Soviet War (1919-21), for which he was awarded the Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military award.

Early on, when the Squadron still lacked suitable insignia, Chess suggested a design (see image), apparently first sketched on a menu of the Hotel George in Lwów. With only minor variations, this insignia remained in use until after the second world war. According to Lynne Olson and Stanley Cloud in A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II, the insignia includes “the red, four-cornered military cap that Kosciuszko wore in the uprising of 1794, plus two crossed scythes, representing the Polish peasants who had followed him into battle… superimposed on a background of red, white and blue stars and stripes representing the U.S. flag.”

Early on, when the Squadron still lacked suitable insignia, Chess suggested a design (see image), apparently first sketched on a menu of the Hotel George in Lwów. With only minor variations, this insignia remained in use until after the second world war. According to Lynne Olson and Stanley Cloud in A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II, the insignia includes “the red, four-cornered military cap that Kosciuszko wore in the uprising of 1794, plus two crossed scythes, representing the Polish peasants who had followed him into battle… superimposed on a background of red, white and blue stars and stripes representing the U.S. flag.”

In the Second World War the “Kosciuszko” Polish Fighter Squadron No. 303 was the highest scoring of all RAF squadrons in the Battle of Britain.

Captain Elliot Chess, who served in WWII in the “A” Troop Carrier Group of the Ninth Air Force, was presented with his “Polish Pilot’s Wings” at a special ceremony in June 1944.

In the 1920s, after the end of the Polish-Soviet War, Chess returned to El Paso and worked as an advertising manager with the El Paso Times. The biography of him on his 1941 novel’s inside back cover says that, since the first world war, “he has been a miner, an editor, a newspaperman, an advertising copy writer, a professional wrestler, a stunt flyer, a short story writer and a dramatist.”

Chess had fulfilled a childhood dream by becoming a published writer. He wrote numerous short stories and novelettes, published between 1929 and 1932, in magazines such as Sky Birds, Sky Riders, Aces, War Birds, War Aces, Flying Aces and Air Stories. He also worked for Liberty magazine.

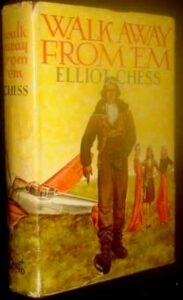

In 1941, his first and only novel, Walk Away From ‘Em, was published by Coward-McCann. Nick Wayne, the hero of his novel is (no real surprise here!) a transatlantic pilot, who “tangles with three women – his ex-wife, Jo, a neurotic dipsomaniac, Fran, and Toddy Fate, young and untouched”. (Kirkus Review, which summarized it as “pop stuff” but “better than usual of its kind”).

In 1941, his first and only novel, Walk Away From ‘Em, was published by Coward-McCann. Nick Wayne, the hero of his novel is (no real surprise here!) a transatlantic pilot, who “tangles with three women – his ex-wife, Jo, a neurotic dipsomaniac, Fran, and Toddy Fate, young and untouched”. (Kirkus Review, which summarized it as “pop stuff” but “better than usual of its kind”).

The Elliot Chess papers, in the C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department of The University of Texas at El Paso Library, include drafts of two plays, Passport to Heaven, and Call it Comic Strip, as well as notes, photographs and other material.

It is unclear why Chess chose to spend the latter part of 1946 in Ajijic, but his sojourn there had several unexpected consequences. Already in residence at Casa Heuer (a small, rather primitive guest house on the lakefront run by a German brother and sister) was an attractive, more serious, younger writer, Elaine Gottlieb.

Despite their sixteen-year difference in age and their contrasting backgrounds (or maybe because of them?), the two hit it off almost immediately, with Gottlieb spellbound by Chess’s magnetism and captivating story-telling. According to Gottlieb, they lived together as man and wife for two months, from mid-September (when they were on a bus to Guadalajara that was attacked by gunmen) to mid-November, at which point Elliot Chess returned to El Paso, claiming he would sell some land he owned there and rejoin her in New York in two weeks. Gottlieb, meanwhile, traveled by train to Mexico City and then to New York. Chess never made it to New York, and the two never met again, but Gottlieb gave birth to their daughter, Nola Elian Chess, in New York City on 3 July 1947. (Nola’s middle name is a combination of Elliot and Elaine).

We can only speculate as to whether Elliot Chess’s aversion to moving to New York was in any way connected to his prior marriage there in 1930 to a “Jean B. Wallace”. It is equally plausible that Chess had no desire to be a father, having never known his own father.

Chess died in El Paso, Texas, on 27 December 1962, at the age of 63, but left no will. When his aunt claimed to be the sole beneficiary, Elaine Gottlieb sought to establish that her daughter (whose birth certificate listed Elliot Chess as father) was entitled to a share of his estate. The case hinged on whether or not Nola was Chess’s legitimate child. Had Gottlieb and Chess ever celebrated a legal marriage? In documents filed with the court, Gottlieb claimed that she believed they had been legally married, though she had no marriage certificate. The somewhat convoluted story is retold by Robin Hemley in Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness. Gottlieb, who by then had married Cecil Hemley, failed to convince the court which concluded, even after an appeal in 1967, that Nola had no right whatsoever to any part of her father’s estate.

Chess died in El Paso, Texas, on 27 December 1962, at the age of 63, but left no will. When his aunt claimed to be the sole beneficiary, Elaine Gottlieb sought to establish that her daughter (whose birth certificate listed Elliot Chess as father) was entitled to a share of his estate. The case hinged on whether or not Nola was Chess’s legitimate child. Had Gottlieb and Chess ever celebrated a legal marriage? In documents filed with the court, Gottlieb claimed that she believed they had been legally married, though she had no marriage certificate. The somewhat convoluted story is retold by Robin Hemley in Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness. Gottlieb, who by then had married Cecil Hemley, failed to convince the court which concluded, even after an appeal in 1967, that Nola had no right whatsoever to any part of her father’s estate.

Elaine Gottlieb Hemley… testified substantially as follows:

“I married Elliot Chess September 15, 1946, in Ajijic, Mexico, and lived with him until on or about November 16, 1946. Elliot did not make an application for a marriage license in the Republic of Mexico. I have no written evidence that I was married to Elliot. It wasn’t that kind of marriage. I said to him, ‘I take thee Elliot to be my lawful wedded husband’ and he said to me, ‘I take Elaine to be my lawful wedded wife.’ I did not sign a civil registry of our marriage in the Republic of Mexico. Neither Elliot nor I appeared before any public official, by proxy or otherwise, to be married. On November 17th I boarded a train for Mexico City. Elliot kissed me goodbye at the hotel early that morning and that was the last time I saw him. I returned to New York and the appellant was born on July 3rd, 1947. Elliot Chess is the father of Nola Elian Chess.” (Court of Civil Appeals of Texas, Eastland.416 S.W.2d 492 (Tex. Civ. App. 1967) BUNTING V. CHESS).

Robin Hemley’s Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness is a detailed account of his older, and brilliant, step-sister Nola’s life and descent into schizophrenia, and how it affected the entire family, including Elaine Gottlieb. It is an uplifting, if at times harrowing, read.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

I have multiple letters written by Elliot chess during those years to his mistress in San Francisco. I have many letters. I can be contacted at my email.

Thanks for your very exciting comment! I’ve replied via email, TB.