One of the earliest known English-language short stories related to Lake Chapala is “The White Rebozo: A Vision of the Night on the Mystic Waters of Lake Chapala,” written by Gwendolen Overton and first published in The Argonaut in July 1900. The story was subsequently reprinted in newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic. In the following transcription, accents have been added and the letter ñ used where appropriate in order to facilitate reading.

The White Rebozo: A Vision of the Night on the Mystic Waters of Lake Chapala

“She is white, yes.” Nuñez spoke English with ease and a charming accent, and he never lost the opportunity of doing so. He was practising now on Lingard, as they stood together at the water’s edge.

Linguard continued to look after the woman who had just gone by them, toward the village. She wore the blue rebozo of the Indian woman, but underneath it you could see that she was fair – fair and of a less classic build than the women of the land.

“She is white, yes. It is because that she is an American, like yourself.”

“An American?” said Lingard, “in that dress?”

He doubted; but the Mexican nodded his head. “An American, yes. I do not know her name. They call her ‘La Gringa,’ only. She is your countrywoman, and she lives in the village there. She loved a man of the people, an Indio, many years ago – and it is like this now. She lives in a small house with two chambers, and she is very poor. She has one daughter who is a little mad. It is because that La Gringa tried to drown herself in this lake before the child was born.”

“And the man?” asked Lingard; “where is he?”

Nuñez shrugged his shoulders, which would have been a little sloping had it not been for the best English tailor of the capital. “Ah! The man. Who knows? He is gone. It is always like that.”

The woman had passed out of sight up the little street, and Lingard turned away, looking thoughtfully up to one of the mountain peaks that rose above the lake. “Am American,” he said, half to himself; “she must have led the life of the dammed. And her eyes were so child-like and blue.”

The Mexican laughed, the laugh of a breed which does not believe in woman except for purpose of poetry and patron saints. “Child-like and blue,” he echoed; “the eyes of women do not show the things which are under them. They are like this lake, I think. It is so blue and beautiful. You would never know that there is a city far down beneath the water, eh?”

Lingard forgot the woman. “A city – under this lake?”

The Mexican was delighted with his effect and the still further chance of more display of English. “You do not know the story of Lake Chapala, then?” Truly. Under it, so deep, deep under it – it is very profound – there is a city, an Aztec city, perhaps. The lake came, I think, maybe, by an earthquake. It was like Pompeii, but that it was buried by water and not by cinders. Some times, when there is a storm, after it you can find on the shore little things which the water bring up; carved stones, little gods, little spools, like for the embroidery and the sewing; little cups, always of stone, and always very small, so that they shall not be too heavy.”

They called to him from the balcony of the hotel and he went away, with a princely sweep of his begilt and besilver sombrero.

Lingard watched him absently for a moment, then he turned his back to the bright waters of the lake, and to fancying the city underneath, somewhere far down, down in the cool, deep blue. The sun of the south might rise over the encircling peaks in the west, and sink behind them in the west; the shadows of the mountains might quiver on the waters’ face, and the flowers of the garden-land wave and bend upon their very edge; but there would always be that ancient city down below, the same cold swing of shore-bound tide. And where butterflies and sweet-throated sanatitas [New World blackbirds] had been, there was now only the little white Lake Chapala fish. It took possession of him, the thought, and also the wise, to find for himself one of the relics of carved stone that the waves moved up from the depths. He wandered on and on along the shore, looking down at the pebbles and the sand.

It was dusk when he came back to the hotel. The señoritas, too modest to bathe in the dull light of day and the sight of man, were splashing about, vague, shapeless shapes at the shore’s edge. Lingard was only a gringo, and he did no know that the beach was sacred to the feminine just then, and that if one wished to watch one should do so from a hotel window with a pair of opera glasses. He did not care to watch, indeed. He considered these maidens who boasted Spanish blood inferior in every respect to the fine dark women of the lower class. And their figures looked execrable in the bathing suits! So he went by almost unheeding, and on into the hotel.

Nuñez was there, killing time in the cantina after the manner of his kind. He seized upon Lingard as a diversion.

“You have dreamed all day by the lake. The ghost of the lake will take you one time.”

“Is there a ghost?” asked Lingard; “I was looking for a stone.”

“One of the carved stones? I will buy one for you, if you will accept it, señor.” The Mexican rejoices to give. “I know where one is to be bought. But there is many that are not genuine – not good – which the Indios make to sell to the excursionists. The one I will give to you shall be genuine.”

Lingard did not want one that was bought, but he felt that he could hardly say so. He told Nuñez that he was very kind, and forthwith discouraged further talk about the lake. Nuñez was a Latin, and it was Lingard’s experience of his sort that there is a strain of deadly bathos in their conversation which grates on the Anglo-Saxon, who is more consistently poetical when he chooses to be a poet, as he is more thoroughly a trader when he elects to trade.

When the moon had begun to rise in a sky that was blowing over with heavy, white-edged clouds, he went out on the lake shore again. There was a whine of wind now, and the slap of the wavelets on the sand was sharper, and sometimes the moon would sail behind a cloud and leave the world in darkness.

Lingard walked on until he was too far from the hotel to hear the shrill chatter of Nuñez and his friends. Then he stood still and looked across the lake. He was thinking yet of the city below the gold-tipped ripples. And as he looked the gold vanished and left the waters black. The moon was behind a cloud. It stayed so for a while, and then came drifting forth, and Lingard, staring straight before him, with glassy eyes, felt the blood running cold in his heart. For there in front of him, not twenty feet away, a woman’s figure stood, slight and frail against the path of moonlight, at the edge of the shore – a figure white-shrouded from head to feet, indistinct against the shimmer, pale-faced and pale-eyed. It held a sheaf of the white flowers of the field clasped in transparent hands against the breast; but they dripped bright drops of water to the ground. “Qué quiere?” Lingard demanded and tried hard to make it firm.

“Tu alma, tu vida,” moaned a voice that whispered with the lapping of the waves and the whistle of the rising wind. “His soul, his life!”

He tried to reason back his fear. It was born of the fancies that he had dreamed over all day, of the tequila he had drunk with Nuñez before dinner, of the fever of the country perhaps. He might be getting the fever now. But the slight boldness that came to him was born of sheer terror, and he fell back on the harshness of his own tongue to break the spell. “Go to the dickens.” he said, crossly, and yet with awe, and took a step nearer to the vague thing.

“Come with me, come with me. The water is calling. The water is deep.” The English that answered was as sure as his own.

He was losing his mind, surely it was the fever. Did spirits speak in every tongue? “Who are you?”

She laughed sweetly, uncannily, and kept on. “There is no more sorrow in the lake, deep down in the lake. I can go to it now. We can go together. Come with me, come.”

“Who are you?” he insisted still. “Tell me who you are.”

One of the hand left her breast and waved toward the water behind her. The light was glowing faint again, and the voice came out of the darkness soon. “We can go in the water now.” And it shouted the words of the song, “Venga conmigo, adonde vivo you.” The shrill, unreal laugh once more, “Que sí señor, que sí señor!” Then it changed to a minor wail and the words of a language Lingard guessed to be that which the Indians of the far recesses of the country still sometimes speak – the language of those who had lived in the lake city, perhaps.

He was stiff, half helpless with fear. The clouds were thicker every minute, and the rifts were smaller and farther between. The song came breathing out of the blackness, sounding first close to him, and then far over upon the lake. He started forward with a sudden resolve to shake it into silence or bring it to a more earthly tone. But he touched something so cold and wet that his fingers were left empty and quite as cold. The waves licked around his feet.

Then the moon came out and he saw the thing, still standing in the path of its rays, but further out in the water that rose even to his knees. Her hands were outstretched in the sign of the cross, as the peons pray, and a white scarf floated over them from her head. The sheaf of flowers had fallen and was drifting softly to the shore. “Quién está?” he repeated helplessly. “Who are you?”

There was no reply; but the pale eyes were looking into his, and they seemed to draw him on.

“Venga conmigo adonde, vovo yo-o-o-o-o.” The sound kept on, drawn out until it was like the faint, far-away cry of a fog-horn at sea. “Come with me, where I live,” she sang, weirdly; and he went, following step by step, drawn on by fear and uncertainty, and the light unwavering eyes. The waters were at her waist now, and the scattered flowers floated against his own knees. The voice took up the wailing Indian song again, and it seemed to come from the waters, as they mounted up to her chin. The arms were still stretched out and the scarf lay on the waves. But the moon was hiding itself yet once more, and the wind was beginning to howl.

Then suddenly the chant stopped and Lingard heard a gasp, a cry, a horribly human cry, choked off in the midst. He was awake now, only too much awake. He remembered that he had been told how the bottom of the lake shelved abruptly, in places, to a great depth, and he remembered, too, that he could not swim. But just out there, beyond him, he could hear the beating and splashing of arms and the frantic struggle with a breathless death, and though there were no strange eyes to lead him now, he went on.

Te next day at morning, when the storm had raised, but the winds and the waves were not yet still, a group of peons were huddled upon the beach. And a woman on the outskirts was screaming as two mozos held her back. “Is it my child?” she cried, not in English, now in Spanish.

“No, it is not your child,” they told her; “It is the gringo. Come away.”

Nuñez left them and strolled over to a moza who stood hugging her arms with grief. “What is the matter with La Gringa?” he asked, “has she lost her child?”

The woman gulped down her sobs. “Yes, señor. The child was mad for many years – only a little mad, in one thing. She wished always to throw herself into the lake. She said that it called to her. It was because her mother was almost drowned once in there before la niña was born. Last night she went away, la niña, when the mother did not know. We searched for her all the night. And now she is dead, señor.”

“Dead?” said Nuñez . “But how do you know?”

She raised her head from her hands and nodded toward the group below. “She did not dress like us, señor, but always all in white; even her rebozo was white like the snow. And you have seen what the gringo holds in his hand, señor – a white rebozo?”

– – o – –

Source

- Gwendolen Overton. 1900. “The White Rebozo.” The Argonaut (San Francisco), 23 July 1900, 4.

This article is reproduced here in the belief that it is no longer enjoys any copyright protection.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, via comments feature or email.

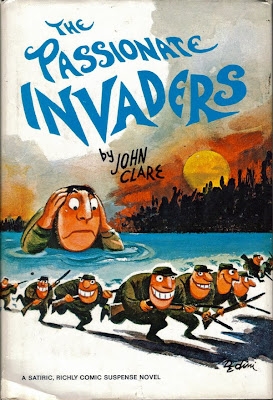

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

John Purvis Clare (1910-1991), who studied at the University of Saskatchewan, served as a public relations officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in North Africa. During his lengthy journalistic career, Clare worked for The Saskatoon Star Phoenix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Telegram, and was the war correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star, as well as managing editor of MacLean’s Magazine and an editor at Chatelaine and Geos. His short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and many other magazines. He also wrote The Passionate Invaders, a humorous novel, published in 1965, about ‘the first armed invasion of the United States from Canada in more than a hundred years.’

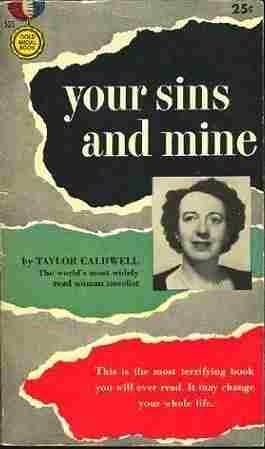

After the death of her second husband, Caldwell had a brief marriage with William Stancell before marrying Canadian William Robert Prestie in 1978.

After the death of her second husband, Caldwell had a brief marriage with William Stancell before marrying Canadian William Robert Prestie in 1978.![Gwendolen Overton, c 1903 [Ancestry]](https://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Overton-Gwendolyn-ca-1903-toverton185.jpg)

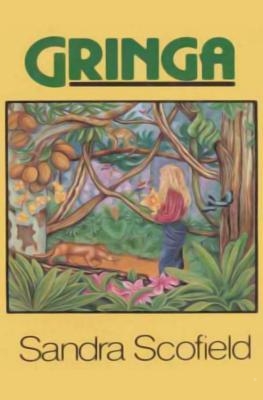

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.

The “gringa” of the book’s title is Abilene “Abby” Painter, a 25-year-old Texan who is trapped in “an abusive, torrid relationship” with Antonio Velez, a famous Mexican bullfighter. In the words of Publishers Weekly, “her self-esteem is so paltry that she serves as a sexual doormat for her swaggering lover” whose “pride in his animal trophies points up the obvious analogy between his mistresses and these slain creatures.” The student protests and their aftermath finally open Abby’s eyes to what she really wants, but can she escape without losing her life? In addition to sex, violence and death, the book explores the full range of animal instincts and the dichotomy between chance and choice in individuals’ lives.

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.

James Brendan Patterson was born in Newburgh, New York, on 22 March 1947. He graduated with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College and an M.A. in English from Vanderbilt University. He was studying for a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt when he took a job in advertising. He became an advertising executive at J. Walter Thompson (and the firm’s North American CEO from 1988) and combined this career with writing until 1996 when he finally retired from advertising to focus all his energies on writing and the promotion of reading. As an ardent philanthropist, Patterson has given away millions of books to schools and the military and funded dozens of reading programs, university grants and scholarships.

Johnny Bogan is set in a small town and is a character study and love story rolled into one. The striking cover art by Puerto Rican artist

Johnny Bogan is set in a small town and is a character study and love story rolled into one. The striking cover art by Puerto Rican artist

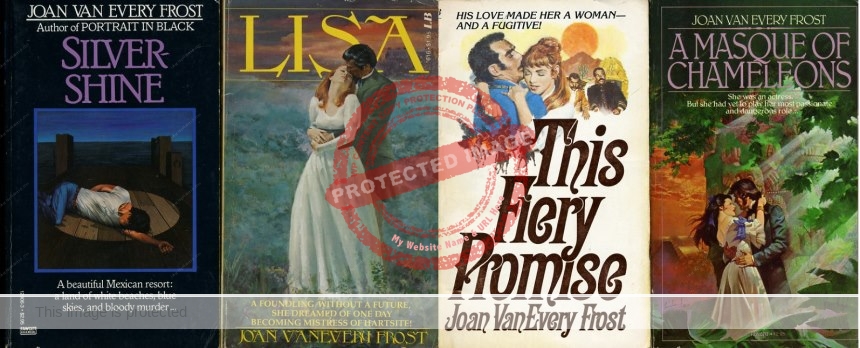

Later, when Jan was studying at the University of Texas at El Paso, she met and married artist Wesley Penn. Penn had friends who lived at Lake Chapala and suggested that they live in Mexico. Jan quickly agreed when she learned that Mexico wanted more English teachers ahead of hosting the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Later, when Jan was studying at the University of Texas at El Paso, she met and married artist Wesley Penn. Penn had friends who lived at Lake Chapala and suggested that they live in Mexico. Jan quickly agreed when she learned that Mexico wanted more English teachers ahead of hosting the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

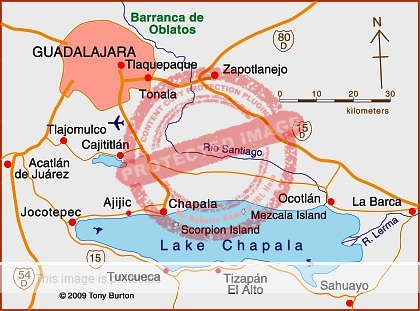

The Sudden View was first published in 1953 and later re-issued as A Visit to Don Otavio, the title by which it is now generally known. The book was based on a trip to Mexico in 1946-47. The book opens in New York as the author and her traveling companion, Esther Murphy Arthur (“E” in the book), start their train journey south. After exploring Mexico City and its environs, they then traveled to Guadalajara via Lake Pátzcuaro and Morelia. The remainder of the book is set almost entirely at Lake Chapala, with several relatively short and adventurous forays to other parts of the country.

The Sudden View was first published in 1953 and later re-issued as A Visit to Don Otavio, the title by which it is now generally known. The book was based on a trip to Mexico in 1946-47. The book opens in New York as the author and her traveling companion, Esther Murphy Arthur (“E” in the book), start their train journey south. After exploring Mexico City and its environs, they then traveled to Guadalajara via Lake Pátzcuaro and Morelia. The remainder of the book is set almost entirely at Lake Chapala, with several relatively short and adventurous forays to other parts of the country.