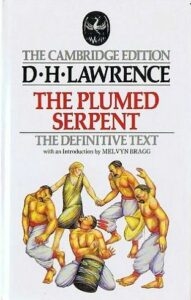

English novelist, poet and essayist David Herbert Lawrence was 37 years of age in summer 1923 when he spent three months in Chapala writing the first draft of the work that eventually became The Plumed Serpent (1926).

For an account of Lawrence’s time in Chapala, see D. H. Lawrence found inspiration in 1923 at Lake Chapala.

The first version of The Plumed Serpent, very different to the final version, was titled Quetzalcoatl and completed in Chapala. Lawrence revised this early version the following year during a visit to Oaxaca. The Plumed Serpent was published in 1926. In 1995, long after Lawrence’s death, the original version, Quetzalcoatl, was also published.

If you haven’t yet read The Plumed Serpent, the entire text is available online:

- Entire text of The Plumed Serpent (Gutenberg.net)

The Plumed Serpent has been extensively analyzed by literary experts. (One of the most interesting of these analyses is L. D. Clark’s Dark Night of the Body: D. H. Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent, Univ. of Texas, 1964). The purpose of this article is not to delve into literary criticism but to highlight some of the salient links between Lawrence’s novel, his time in Mexico and, in particular, his months at Lake Chapala.

Outline plot

The plot, as described on the back cover of some editions of The Plumed Serpent:

“Kate Leslie, an Irish widow visiting Mexico, finds herself equally repelled and fascinated by what she sees as the primitive cruelty of the country. As she becomes involved with Don Ramon and General Cipriano, her perceptions change. Caught up in the plans of these two men to revive the old Aztec religion and political order, she submits to the ‘blood-consciousness’ and phallic power that they represent.”

Differences between Quetzalcoatl and The Plumed Serpent

Literary scholars have subjected the differences between the two versions to reams of analysis. Lawrence made dozens of important changes, but the most significant difference comes in how he developed the character of his heroine, Kate. In the original version, Quetzalcoatl, Kate did not agree to marry General Cipriano Viedma, did not agree to become the manifestation of the rain-goddess, and did not agree to remain in Mexico.

The characters in the novel

Many of the events in The Plumed Serpent are based on experiences Lawrence had in Mexico, and many of the characters are based on people in his immediate circle or people he met during his trip.

Many of the events in The Plumed Serpent are based on experiences Lawrence had in Mexico, and many of the characters are based on people in his immediate circle or people he met during his trip.

Some of Lawrence’s minor characters can readily be linked to real people. For instance, his portrayal of the Americans Owen Rhys and Bud Villiers at the bullfight was based on his traveling companions Witter Bynner and Willard (“Spud”) Johnson respectively.

The archaeologist Mrs Norris (Chapter II), who hosted a memorable tea party, was, in real life, Mrs Zelia Nuttall (1858-1933).

The young Mexican who conducted the tour of the frescoes in Mexico City (chapter III) was Mexican artist-geographer Miguel Covarrubias (See Mexican artist-geographer helped put Bali on the tourist map and Mexico in the USA: Pacific fauna and flora mural in San Francisco).

The family of Mexicans at Kate’s house (chapters VIII and IX) was based on the Mexican family that helped look after Lawrence and his wife Frieda in their home in Chapala.

Bell, the American hotel owner in chapter VI, was based on hotelier-photographer Winfield Scott, who at one time had managed the Hotel Ribera Castellanos, but in 1923 was managing the Hotel Arzapalo in Chapala, the hotel where Lawrence’s traveling companions Bynner and Johnson stayed. (The Hotel Ribera Castellanos has various literary claims to fame dating back to the mid-nineteenth century.)

The more complex characters in The Plumed Serpent are, in all likelihood, fictional amalgams of several real people. The personality and actions of Don Ramón, for instance, are said to echo José Vasconcelas, the Mexican Education Minister at the time of Lawrence’s visit, combined perhaps with elements of General Arnulfo Gómez, who Lawrence met in Cuernavaca. Witter Bynner, in Journey with Genius, suggests that an American ex-boxer John Dibrell, then resident in Chapala, also influenced the character of Don Ramón.

Cipriano in the novel adopts tactics similar to those espoused by General Gómez, but other details of his life are surely based on the early life of Benito Juárez, the nineteenth century reformer, of humble origin, who served five terms as Mexico’s president.

The landscapes and villages of Lake Chapala

The Plumed Serpent includes many locales that clearly relate to specific places Lawrence visited during his three months in Chapala in 1923. Almost all of the place names Lawrence uses in the novel are the names of real places in the Lake Chapala area, though Lawrence “reassigns” them in his novel.

For example, Lake Chapala itself is fictionalized as “Lake Sayula” in the novel. (Sayula is the name of a town and shallow lake to the west of the real Lake Chapala.) Even though Lawrence stayed at Lake Chapala into the summer rainy season, when the local vegetation is at its most verdant, in chapter 5 of The Plumed Serpent, where Kate arrives at the lake, he deliberately paints only an unflattering dry-season description of the lake’s surrounding countryside:

Dry country with mesquite bushes, in the dawn: then green wheat alternating with ripe wheat. And men already in the pale, ripened wheat reaping with sickles, cutting short little handfuls from the short straw. A bright sky, with a bluish shadow on earth. Parched slopes with ragged maize stubble. Then a forlorn hacienda and a man on horseback, in a blanket, driving a silent flock of cows, sheep, bulls, goats, lambs, rippling a bit ghostly in the dawn, from under a tottering archway. A long canal beside the railway, a long canal paved with bright green leaves from which poked the mauve heads of the lirio, the water hyacinth. The sun was lifting up, red. In a moment it was the full, dazzling gold of a Mexican morning.”

Ixtlahuacan (chapter V), with its railway station, was Lawrence’s name for the town of Ocotlán. The nearby Orilla Hotel (chapters V, VI) was (in reality) the once prominent Hotel Ribera Castellanos. In the novel, Kate was greeted by the hotel manager:

He showed Kate to her room in the unfinished quarter, and ordered her breakfast. The hotel consisted of an old low ranch-house with a veranda — and this was the dining-room, lounge, kitchen, and office. Then there was a two-storey new wing, with a smart bathroom between each two bedrooms, and almost up-to-date fittings: very incongruous.

But the new wing was unfinished — had been unfinished for a dozen years and more, the work abandoned when Porfirio Diaz fled. Now it would probably never be finished. (chapter V)

In the following chapter, Lawrence expands his explanation of the hotel’s recent history:

In Porfirio Diaz’ day, the lake-side began to be the Riviera of Mexico, and Orilla was to be the Nice, or at least the Mentone of the country. But revolutions started erupting again, and in 1911 Don Porfirio fled to Paris with, it is said, thirty million gold pesos in his pocket: a peso being half a dollar, nearly half-a-crown. But we need not believe all that is said, especially by a man’s enemies.

During the subsequent revolutions, Orilla, which had begun to be a winter paradise for the Americans, lapsed back into barbarism and broken brickwork. In 1921 a feeble new start had been made.

The place belonged to a German-Mexican family, who also owned the adjacent hacienda. They acquired the property from the American Hotel Company, who had undertaken to develop the lake-shore, and who had gone bankrupt during the various revolutions.

The German-Mexican owners were not popular with the natives. An angel from heaven would not have been popular, these years, if he had been known as the owner of property. However, in 1921 the hotel was very modestly opened again, with an American manager. (chapter VI)

Lawrence uses Kate’s boat ride from Orilla to Sayula (Chapala) to include a thumb nail account of the historically-important Island of Mezcala:

They were passing the island, with its ruins of fortress and prison. It was all rock and dryness, with great broken walls and the shell of a church among its hurtful stones and its dry grey herbage. For a long time the Indians had defended it against the Spaniards. Then the Spaniards used the island as a fortress against the Indians. Later, as a penal settlement. And now the place was a ruin, repellent, full of scorpions, and otherwise empty of life. Only one or two fishermen lived in the tiny cove facing the mainland, and a flock of goats, specks of life creeping among the rocks. And an unhappy fellow put there by the Government to register the weather. (chapter VI)

The village of Sayula itself, where most of the book’s action takes place, is, of course, based on the village of Chapala, complete with its hot pools and (in 1923) newly-opened railway station:

‘Sayula!’ said the man in the bows, pointing ahead.

She saw, away off, a place where there were green trees, where the shore was flat, and a biggish building stood out.

‘What is the building?’ she asked.

‘The railway station.’

She was suitably impressed, for it was a new-looking, imposing structure.

A little steamer was smoking, lying off from a wooden jetty in the loneliness, and black, laden boats were poling out to her, and merging back to shore. The vessel gave a hoot, and slowly yet busily set off on the bosom of the water, heading in a slanting line across the lake, to which the tiny high white twin-towers of Tuliapán showed above the water-line, tiny and far-off, on the other side.

They had passed the jetty, and rounding the shoal where the willows grew, she could see Sayula; white fluted twin-towers of the church, obelisk shaped above the pepper-trees; beyond, a mound of a hill standing alone, dotted with dry bushes, distinct and Japanese-looking; beyond this, the corrugated, blue-ribbed, flat-flanked mountains of Mexico.

It looked peaceful, delicate, almost Japanese. As she drew nearer she saw the beach with the washing spread on the sand; the fleecy green willow-trees and pepper-trees, and the villas in foliage and flowers, hanging magenta curtains of bougainvillea, red dots of hibiscus, pink abundance of tall oleander trees; occasional palm-trees sticking out.

The boat was steering round a stone jetty, on which, in black letters, was painted an advertisement for motor-car tyres. There were a few seats, some deep fleecy trees growing out of the sand, a booth for selling drinks, a little promenade, and white boats on a sandy beach. A few women sitting under parasols, a few bathers in the water, and trees in front of the few villas deep in green or blazing scarlet blossoms.

‘This is very good,’ thought Kate. ‘It is not too savage, and not over-civilized. It isn’t broken, but it is rather out of repair. It is in contact with the world, but the world has got a very weak grip on it.’

She went to the hotel, as Don Ramón had advised her. (Chapter VI)

Lawrence opens chapter VII with a more in-depth look at the village:

Sayula was a little lake resort; not for the idle rich, for Mexico has few left; but for tradespeople from Guadalajara, and week-enders. Even of these, there were few.

Nevertheless, there were two hotels, left over, really, from the safe quiet days of Don Porfirio, as were most of the villas. The outlying villas were shut up, some of them abandoned. Those in the village lived in a perpetual quake of fear. There were many terrors, but the two regnant were bandits and bolshevists.

Sayula had her little branch of railway, her one train a day. The railway did not pay, and fought with extinction. But it was enough.

Sayula also had that real insanity of America, the automobile. As men used to want a horse and a sword, now they want a car. As women used to pine for a home and a box at the theatre, now it is a ‘machine.’ And the poor follow the middle class. There was a perpetual rush of ‘machines’, motor-cars and motor-buses — called camiónes — along the one forlorn road coming to Sayula from Guadalajara. One hope, one faith, one destiny; to ride in a camión, to own a car.” (chapter VII)

At weekends, Sayula really heated up, with the arrival of cityfolk, who presented quite a spectacle to the local peons:

But on Saturdays and Sundays there was something of a show. Then the camiónes and motor-cars came in lurching and hissing. And, like strange birds alighting, you had slim and charming girls in organdie frocks and face-powder and bobbed hair, fluttering into the plaza. There they strolled, arm in arm, brilliant in red organdie and blue chiffon and white muslin and pink and mauve and tangerine frail stuffs, their black hair bobbed out, their dark slim arms interlaced, their dark faces curiously macabre in the heavy make-up; approximating to white, but the white of a clown or a corpse.

In a world of big, handsome peon men, these flappers flapped with butterfly brightness and an incongruous shrillness, manless. The supply of fifis, the male young elegants who are supposed to equate the flappers, was small. But still, fifis there were, in white flannel trousers and white shoes, dark jackets, correct straw hats, and canes. Fifis far more ladylike than the reckless flappers; and far more nervous, wincing. But fifis none the less, gallant, smoking a cigarette with an elegant flourish, talking elegant Castilian, as near as possible, and looking as if they were going to be sacrificed to some Mexican god within a twelvemonth; when they were properly plumped and perfumed. The sacrificial calves being fattened.

On Saturday, the fifis and the flappers and the motor-car people from town–only a forlorn few, after all–tried to be butterfly gay, in sinister Mexico. They hired the musicians with guitars and fiddle, and the jazz music began to quaver, a little too tenderly, without enough kick.” (chapter VII)

At weekends, the village plaza became the center of commercial activity:

It was Saturday, so the plaza was very full, and along the cobbled streets stretching from the square many torches fluttered and wavered upon the ground, illuminating a dark salesman and an array of straw hats, or a heap of straw mats called petates, or pyramids of oranges from across the lake.

It was Saturday, and Sunday morning was market. So, as it were suddenly, the life in the plaza was dense and heavy with potency. The Indians had come in from all the villages, and from far across the lake. And with them they brought the curious heavy potency of life which seems to hum deeper and deeper when they collect together.

In the afternoon, with the wind from the south, the big canoas, sailing-boats with black hulls and one huge sail, had come drifting across the waters, bringing the market-produce and the natives to their gathering ground. All the white specks of villages on the far shore, and on the far-off slopes, had sent their wild quota to the throng. (chapter VII)

The house which Lawrence and his wife Frieda rented in Chapala at Zaragoza #4 became Kate’s living quarters in The Plumed Serpent:

Her house was what she wanted; a low, L-shaped, tiled building with rough red floors and deep veranda, and the other two sides of the patio completed by the thick, dark little mango-forest outside the low wall. The square of the patio, within the precincts of the house and the mango-trees, was gay with oleanders and hibiscus, and there was a basin of water in the seedy grass. The flower-pots along the veranda were full of flowering geranium and foreign flowers. At the far end of the patio the chickens were scratching under the silent motionlessness of ragged banana-trees.

There she had it; her stone, cool, dark house, every room opening on to the veranda; her deep, shady veranda, or piazza, or corridor, looking out to the brilliant sun, the sparkling flowers and the seed-grass, the still water and the yellowing banana-trees, the dark splendour of the shadow-dense mango-trees.

With the house went a Mexican Juana with two thick-haired daughters and one son. This family lived in a den at the back of the projecting bay of the dining-room. There, half screened, was the well and the toilet, and a little kitchen and a sleeping-room where the family slept on mats on the floor. There the paltry chickens paddled, and the banana-trees made a chitter as the wind came.” (chapter IX)

Early in the day, Kate would sit on the veranda:

Morning! Brilliant sun pouring into the patio, on the hibiscus flowers and the fluttering yellow and green rags of the banana-trees. Birds swiftly coming and going, with tropical suddenness. In the dense shadow of the mango-grove, white-clad Indians going like ghosts. The sense of fierce sun and, almost more impressive, of dark, intense shadow. A twitter of life, yet a certain heavy weight of silence. A dazzling flicker and brilliance of light, yet the feeling of weight.” (chapter IX)

The imposing, twin-spired church (chapters XVI and XVIII) was only a few steps away from the house Lawrence rented in Chapala.

Jamiltepec, Don Ramón’s hacienda on Lake Sayula (chapter VI onwards) was based on the mansion Villa El Manglar, owned by in-laws of President Porfirio Díaz, which was partially ruined in 1923.

Other obvious parallels include the market scene (chapter VII), and the novel’s depictions of women washing clothes and men fishing for charales (chapter IX).

Lawrence’s wife Frieda, in her memoir Not I, But the Wind… (1934), also recalls that,

“We went across the pale Lake of Chapala to a native village where they made serapes; they dyed the wool and wove them on simple looms. Lawrence made some designs and had them woven, as in the “Plumed Serpent”.

These examples should suffice to show just how keenly Lawrence observed everyone and everything around him during his months in Chapala, as well as how widely he read about Mexico’s history, both ancient and modern.

Why was there never a movie version?

Somewhat surprisingly, Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent has never been made into a movie.

Apparently, there was a 1970 screenplay by Robert Bolt (who wrote Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago and A Man for All Seasons) that Christopher Miles hoped to direct, but this project never came to fruition. Miles wanted his sister (and Robert Bolt’s wife) Sarah Miles, the English actress who starred in Ryan’s Daughter, to play “Kate Leslie” and Oliver Reed to be “Cipriano”. In a 1973 newspaper article, Sarah is quoted as saying, “I’m going to star in ‘The Plumed Serpent‘ on location in Argentina. Robert has written the screenplay from a D.H. Lawrence story. And my brother Christopher is going to direct.” (Long Beach Independent, 9 April, 1973).

To learn more about what Lake Chapala was like when Lawrence visited, see (a) If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants (translated into Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes), (b) Lake Chapala: A Postcard History which uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center, and (c) Hotel Ribera Castellanos and the Lake Chapala Agricultural and Improvement Company.

Sources:

- Witter Bynner. 1951. Journey with Genius (New York: John Day)

- L. D. Clark. 1964. Dark Night of the Body: D. H. Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent. (Univ. of Texas)

- D. H. Lawrence. 1923 (published 1995) Quetzalcoatl.

- D. H. Lawrence. 1926. The Plumed Serpent.

Comments and suggestions welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Can you kindly tell me whether any elements of travel-narrative, Mornings in Mexico, have been found in his novel: The Plumed Serpent? And whether there are any characters in similarity bn both these books of Lawrence as we know both of these books were worked upon at the same time?

I’m not aware of any connections between the two works (apart from the author). They are set in very different parts of Mexico (and, in the case of Mornings in Mexico, New Mexico). Lawrence had already completed the first draft of The Plumed Serpent well before he visited Oaxaca, where he wrote the second draft of that work and began to compile Mornings in Mexico. TPS is a novel, while MIM is essentially a travelogue, and I’m not aware of any similar characters.