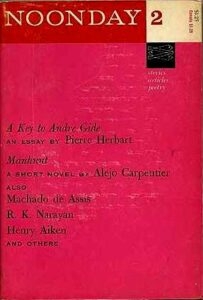

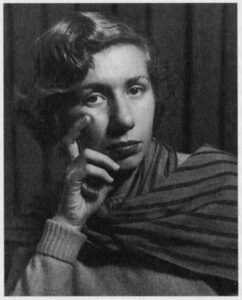

Elaine Gottlieb (1916-2004) was a novelist, author and teacher who lived for several months in Ajijic in the second half of 1946. She traveled to Mexico shortly after completing her first novel, Darkling, which was published the following year. She used her experiences in Ajijic as the basis for a short story, “Passage Through Stars”, published many years later, in Noonday #2, 1959.

Gottlieb’s decision to visit Mexico was apparently at the suggestion of Robert Motherwell, her art teacher one summer at Black Mountain College. (By coincidence, another former Black Mountain College art student, Nicolas Muzenic, lived in Ajijic shortly afterwards, from about 1948 to 1950).

In Ajijic, Gottlieb stayed at the collection of small cottages on the water’s edge known as Casa Heuer, run by a German brother and sister (Pablo and Liesel), where communal dinner was the norm. At mealtimes, Gottlieb found herself drawn to a handsome, smartly-dressed, charismatic older man, Elliot Chess, a flying ace from the first world war whose stories and anecdotes kept his mealtime companions spellbound.

In Ajijic, Gottlieb stayed at the collection of small cottages on the water’s edge known as Casa Heuer, run by a German brother and sister (Pablo and Liesel), where communal dinner was the norm. At mealtimes, Gottlieb found herself drawn to a handsome, smartly-dressed, charismatic older man, Elliot Chess, a flying ace from the first world war whose stories and anecdotes kept his mealtime companions spellbound.

She was 30 years of age, he was 46; within two weeks they were engaged. To celebrate, on 15 September 1946, they caught a bus to Guadalajara. Gunmen attacked the bus and Gottlieb credited Chess with saving her life. Their precipitous, but short-lived, relationship led to the birth of Nola Elian Chess (her middle name is a combination of Elliot and Elaine) in New York in July 1947, which turned out to have life-changing consequences for Gottlieb and her future family.

[Nola, conceived in Mexico and born in New York, developed a brilliant mind, but died at the tragically-young age of twenty-five after a prolonged struggle with schizophrenia. Gottlieb’s younger son, Robin Hemley, has written an absorbing account of the life of his older half-sister: Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness.]

In Gottlieb’s “Passage Through Stars”, Casa Heuer is transformed into Casa Unger, with Elaine becoming Emma and Elliot renamed Claude. The fictional names of the inn’s owners are Don Ernesto and Donna [sic] Sophía. The autobiographical story is a powerfully-told and moving account of her brief fling with Chess, exploring her personal doubts before, during and after.

She recalls her lover’s daily ritual swim in the lake:

“She would see him in the mornings, going down to the lake for his pre-breakfast swim; a shiny maroon robe flapped around his narrow legs. He would walk briskly, towel in hand, remove his robe in two swift movements, step out of his slippers, and, chin erect, approach the lake. Deliberately, he would plunge his head in, shake it vigorously, stand waiting a moment, and then plunge boldly. A little later, he would return, hand passing through his wet, mahogany-colored hair. Frowning against the light, he would continue to walk, martially erect, his head high and handsome, the face still young, eyes like the eyes of tigers.” [Passage Through Stars, 82]

According to Gottlieb, she and Elliot Chess lived together as man and wife there for two months, from mid-September (following the attack on the bus) to mid-November, at which point Chess returned to El Paso, promising to sell some of the land he owned there and rejoin her in New York in two weeks. Gottlieb, meanwhile, traveled by train to Mexico City and then to New York. Chess never made it to New York, and the two never met again.

In “Passage Through Stars”, Gottlieb says that Emma (herself) had “come to the pension alone, a widow, and had never fully recovered from her widowhood. Claude had happened on the scene…” but I have yet to find any mention elsewhere of Gottlieb’s former spouse.

Gottlieb was born in New York City in 1916. Her mother, Ida, was a teacher in the New York Public Schools and eventually established the family home on Long Island. She gained a degree in journalism from New York University and studied art at the Art Students League of New York and at Columbia University. When Gottlieb was 25 years of age, she moved to Manhattan, determined to become a successful writer. During the summer of 1941, she studied at the Cummington School for the Arts.

During the second world war, Gottlieb had a job inspecting radios for the Signal Corps and also trained to teach photography to Army Air Corps recruits in Denver, Colorado.

In 1946, her short story “The Norm”, about an affair between a couple of college students, was chosen for inclusion in Martha Foley’s annual anthology The Best American Short Stories. The biographies attached to that and later stories say she had once sold books at Macy’s and written cables for The Office of War Information, as well as written book reviews for The New Republic, the New York Herald Tribune, Poetry, Accent, and Decision.

Her first (and only) published novel, Darkling (1947), tells the story of Cristabel, a young woman who yearned to become an artist, but was alienated from family and peers, and “lost in her own insecurities”. The book’s subject matter was ahead of its time and contemporary reviews were generally not favorable.

Prior to marrying poet and novelist Cecil Hemley (1914-1966) in 1953, on Nola’s fifth birthday, Elaine Gottlieb had been raising her daughter as a single parent. Despite a succession of family tragedies, Gottlieb continued to write short stories for publications such as The Kenyon Review, Chimera, New Directions, Chelsea Review, Noonday and Commentary, and also wrote “The writer’s signature: idea” in Story and Essay (1972). By the time of her death in 2004, she had still not completed two more novels that she had started many years earlier, including a mystery story based on a trip to England.

The Hemleys socialized with a glittering array of literary and artistic friends (including Robert Motherwell, Joseph Heller, Louise Bogan, Weldon Kees, Conrad Aiken, John Crowe Ransom and Delmore Schwartz) and became particularly close friends with poet and novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978. The Hemleys helped translate and edit, several of Singer’s works from their original Yiddish, including The Manor (Penguin Books, 1975); Gimpel the Fool and Other Stories (Peter Owen Limited, 1958); The Magician of Lublin (Bantam Books 1965); and The Estate (Jonathan Ball, 1970).

Gottlieb taught creative writing, literature and film at Indiana University (South Bend) in the 1970s. Several former students of Gottlieb have acknowledged her role in helping them develop their craft. They include Gloria Anzaldúa, a foremost Chicano feminist thinker and activist, and author of This Bridge Called My Back (1981); Borderlands/La Frontera (1987); and Interviews/Entrevistas (2000).

Elaine Gottlieb was also known as Elaine S. Gottlieb, Elaine Gottlieb Hemley, Elaine S. Gottlieb Hemley and Elaine S. Hemley.

Sources:

- Elaine Gottlieb, 1959. “Passage Through Stars”, in Noonday #2, edited by Cecil Hemley and Dwight W. Webb, p 80-93. (New York: the Noonday Press)

- Robin Hemley, 1998. Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness. (Graywolf Press).

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Elaine was my teacher and mentor at IUSB. She had a private writing group that met at her house and was composed of selected writing students. I recall Robin as a small boy attending our meetings and holding forth (very well) with the adults. I also cut Robin’s hair as a young boy where I worked as a stylist at Michael’s Styling in South Bend. Later, Robin became part of the faculty where I received my MFA, Vermont College.

Les Edgerton,

Author, The Rapist, The Bitch and others.