A bold and ambitious plan was proposed in the 1920s to build a modernist city on the shores of Lake Chapala. The idea, first mooted in 1921, was formalized in 1923 when a 64-page pamphlet was published as the first, and apparently only, issue of The Chapala Round Table. The proposed site was at the eastern end of the lake near La Barca.

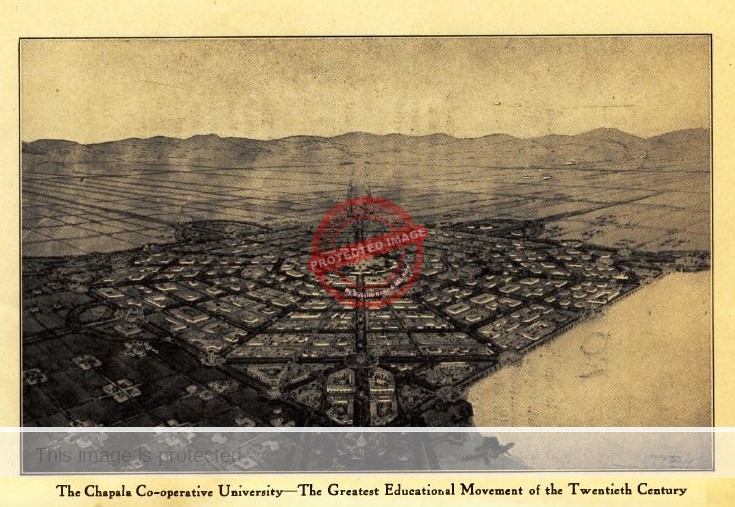

Edited by Orlando Edgar Miller and Alexander Irvine, the pamphlet made the case for establishing the Chapala Co-operative University, “the greatest educational movement of the twentieth century,” in a purpose-built city, where people moved about in “swift moving automobiles or flying machines.”

The Founders League of the Chapala Co-Operative University included Orlando Miller as President and author Alexander Irvine as Chairman. Also on the advisory board were international attorney V. H. Pinckney, electrical engineer L. Earle Browne, mechanical engineer H. Haedler and architect Irving J. Gill, who rendered this illustration, the frontispiece of the published plan:

Irving Gill. 1923. The Chapala Co-Operative University. (The Chapala Round Table, vol 1 #1.)

Irving J. Gill (1870-1936) was a renowned U.S. architect whose innovative designs laid the foundation for modernist architecture in Southern California, where a dozen of his buildings are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. There is no evidence that Gill (1870-1936) or, indeed, most of the other members of the project’s Advisory Board ever visited Lake Chapala. Orlando Miller, however, had first visited the lake in 1921 and had developed good contacts with Mexican government officials.

The city would have a great civic center, wonderful gardens and shady trees. Heat, light and power for the community would come from water; there would be no dust, dirt or smoke. Education would be free. Working age members of the co-operative would be expected to work four hours each day. The university, “in addition to the usual classical, literary and scientific courses, will teach architecture, landscape gardening, city building, civic righteousness and eugenics.” Each home would have almost an acre of land.

Trades and industries, such as dairying, cattle ranching, horticulture, a sanatorium and a hotel, would be set up, and the management of thousands of acres of fertile farmland around the city would help finance its needs. An eight-year financial plan showed how all the necessary expenditures could be met as the city grew to house 25,000 people on its 250,000-hectare site.

The Chapala Round Table pamphlet was illustrated with four small photographs of Lake Chapala: a sunset, perhaps taken at El Fuerte; a panoramic view looking west from Cerro San Miguel in Chapala; a view of Chapala church and the shoreline east of Chapala pier, and an image of Villa Tlalocan, built by British consul Lionel Carden in the 1890s. None of the images are credited in the pamphlet, though the photograph of Villa Tlalocan is definitely the work of Chapala-born photographer José Edmundo Sánchez.

Most of the material in the pamphlet was “reprinted with special permission from the pages of The Psychological Review of Reviews.” However, only a handful of issues of The Psychological Review of Reviews were ever published, and there is no evidence for a second issue of The Chapala Round Table. Like these two magazines, the proposed university-city was a short-lived idea. It was never built, but that’s another story, for another place. (See my article elsewhere: “On To Chapala” — The Chapala University Movement of the 1920s.”)

Miller was not the only person to dream of creating a super city at Lake Chapala. Other luminaries who contemplated establishing a Utopian or intellectual city at Lake Chapala in the twentieth century included Mexican artist Gerardo Murillo, better known as Dr. Atl, and the English novelist D. H. Lawrence, who first visited Chapala only a few months before the publication of The Chapala Round Table.

My 2022 book Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to tell the incredible story of this period and of how Lake Chapala became an international tourist and retirement center.

Sources

- Orlando Edgar Miller & Alexander Irvine (eds). 1923. The Chapala Round Table, Vol 1, #1 (November 1923). [link is to a copy archived by The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals.]

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.