I’ve shared the story of American author Neill James, who arrived in Ajijic for the first time in September 1943, several times previously, with varying degrees of detail, ranging from a summary version of her life to the lengthier, more nuanced version threaded through Foreign Footprints in Ajijic and an in-depth 38-page research paper.

The last two chapters of her final book, Dust on My Heart (1946) describe the village of Ajijic and James’ reactions and adaptations to living there.

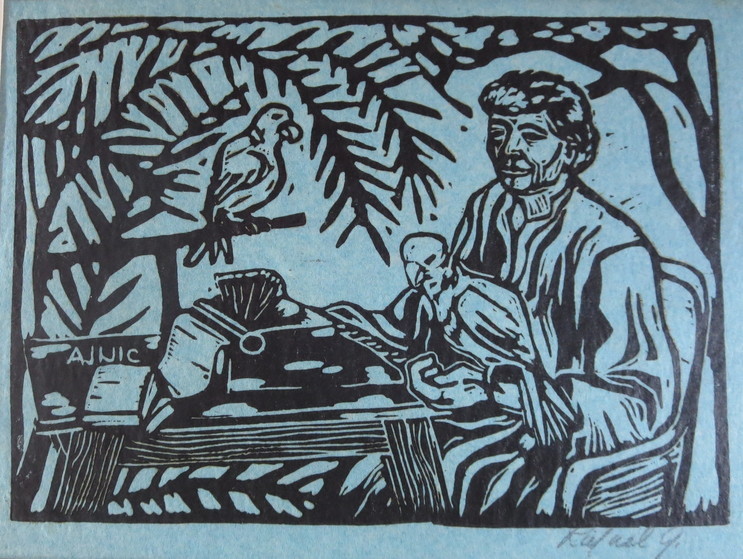

Neill James at her typewriter. Woodblock print by Rafael Greno. c. 1957?

This post considers some of the people—foreigners and locals—mentioned by James in those final two chapters of Dust on My Heart.

Page numbers are for the 1997 Lake Chapala Society reprint of Dust on My Heart.

Marion Morris = Marion Madeline Miedema

p 271: “Marion Morris of San Francisco, an ex-Honolulu friend, who arrived in Mexico just two days before I visited Paricutin, was enthusiastic about Ajijic, and we decided to go there. We left Mexico City September 1, she by plane, I by train, met in Guadalajara and traveled by bus to Chapala. From there we took a small boat up the lake to Ajijic.”

– Marion Madeline Miedema (1909-1994) was a Southern Calfornian educator, writer and historian, who gave illustrated talks on her travels in the 1930s onwards throughout Latin America. Miedema was definitely in Ajijic in June 1947 to witness the signing of Neill James’ book contract for Dust on My Heart, and accompanied James to the Rigall-Masson wedding at Quinta Johnson, Ajijic, on 31 August 1949. By altering her surname and city of origin, James presumably hoped to preserve some degree of anonymity for her friend.

Pablo and Louisa Heuer

p 272-6: “Don Pablo, a sparse, tall German” and “Doña Louisa, a rather buxom German woman with round face.”

– German siblings Paul and Liesel Heuer arrived in Ajijic in the 1930s and ran the rustic lakefront inn where Neill James and Madeline Miedima stayed on their arrival in 1943. James and Liesel Heuer went on several walking expeditions together. See chapter 8 of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic.

German baron and his wife = Alex von Mauch and Eleanor Mason-Armstrong

p 284: “… a German baron who bought the land adjacent to the Heuers…” and story of his mail-order bride and demise.

– Alex von Mauch was an Austrian cellist turned rancher. His bride Eleanor Mason-Armstrong was an English artist resident in California prior to the marriage. See chapter 6 of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic.

Ayenara (Zara) and Holger (and her mother and Quilocho)

p 281-283, 304: “Heuer’s neighbors, the ‘Russians,’ a glamorous and beautiful couple of ballet dancers and their aged mother, owned the best mine.”

– American ballerina Eleanore Saenger (her birth name), aka Zara or ‘La Rusa,’ had bought a gold mine when she first lived in Chapala with her Danish dance partner Holger Mehnen in the mid-1920s. Her mother later joined them in Chapala. The trio moved to Ajijic in 1940. Quilocho was the mine manager’s nickname, as used in the title of Zara’s fictionalized memoir Quilocho and the Dancing Stars. Zara’s story is told via multiple chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic.

Herbert and Georgette Johnson

p 294, 301: “Herbert Johnson, our retired English neighbor, who with his wife Georgette, are refugees from France.”

– Amazon explorer and engineer Herbert Johnson and Georgette built their home and a magnificent garden extending to the beach, at the start of the 1940s. See chapter 9 of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic.

Mrs Hunton

p 302: “Mrs Hunton, who has lived for forty years in Chapala, and who was the model for the heroine in the novel “Mrs Morton of Mexico.”

– Elizabeth Hunton and her husband, British businessman Victor Hunton, settled in Chapala in about 1905. “Mrs Morton of Mexico” was written by Arthur Davison Ficke. See also chapter 31 of If Walls Could Talk.

Doctor Halmos

p 304: After Neill James was accidentally poisoned with arsenic, “Doctor Halmos, a retired physician, formerly head of the Health Department of Chicago, living in Chapala, came, bringing with him a heart stimulant.”

– Dr Alexander Charles Halmos (1881-1960) was a Hungarian-born physician who became a U.S. citizen. His youngest son, Paul Halmos (1916-2006), was a noteworthy American mathematician and professor. Dr. Halmos and his second wife, Hungarian-born Irene Markus Reich (1894-1991), lived in Chapala in the 1940s. Irene, after working as an attorney in Chicago, became a psychotherapist and major philanthropist, who helped found Shelters for Israel, and supported Israeli universities.

Otto Butterlin

p 301: “Otto Butterlin, a well-known artist turned farmer.”

– German-Mexican chemist and artist Otto Butterlin had strong family links to Ajijic. He moved from Mexico City to live there in the 1940s and co-founded Ajijic’s first art gallery.

Sylvia Fein

p 293: “Sylvia Fein, a young American artist living in our village, worked out some original designs.” (for embroidery)

– The great Surrealist painter Sylvia Fein (1919-2024), whose husband was serving overseas at the time, was in Ajijic preparing for her first solo show in New York.

David Nixon and his wife June

p 284-5: “David Nixon, a New Orleans artist, and his wife June…”

– David Nixon was thinking of buying property in Ajijic, but changed his mind on hearing stories of banditry.

Oxford Man (unnamed) = Nigel Millett

p 294: “A young Oxford man said, ‘The invasion bores me stiff. General Eisenhower has a nice face, but he has done nothing to convince me he is not as dumb as the others.'”

– Young British author Nigel Stansbury Millett (1904-1946) and his father, Henry Millett, had moved to Ajijic in 1937. Using the pen name Dane Chandos, Nigel Millett and Peter Lilley co-wrote two superbly written books about the area: House in the Sun and Village in the Sun.

Commander Von Spee

p 287-8: German U-boat commander Von Spee lived in Chapala for a while and drove a car with a Louisiana license plate. Had short wave radio “concealed in a house between Ajijic and Chapala.” A Mexican boy told the secret service men “the short wave was in a house on the road to Chapala, near the lake, which was overshadowed by a big overhanging cliff.” Officers uncovered the short wave, but the boy was brutally killed a few days later. This took place only days before two boats were sunk in Veracruz harbor.

– This must be based on a mix of inaccurate hearsay and conflation of different events.

German U-boat commander Von Spee and both his sons all died in 1914. The vessel Admiral Graf Spee (named for Maximilian von Spee) was launched in June 1934, commissioned in 1936 and scuttled in 1939.

The sinking of two boats in Veracruz harbor may refer to the Tuxpam and the Las Choapas, sunk within hours of each other in June 1942 by U-129, captained by Hans-Ludwig Witt.

Japanese Vice Admiral (unnamed)

p 287: “A Japanese Vice Admiral, with a number of compatriots, worked as day laborers for several months at the mine owned by the Russian ballerina.”

– ???

Japanese doctor (unnamed)

p 287: “Another Japanese, a doctor, spent four pre-war years ministering to the Indians in Pueblo Nuevo, a village in the mountains directly across the lake.”

– ???

German in cemetery (unnamed)

p 284: The first foreigner to need space in the local cemetery was a German. He flirted with a vivacious Señora. An irate husband hacked him into pieces.”

– I believe this is probably a reference to the 1896 murder of Juan Jaacks in Ajijic (chapter 2 of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic). Though Jaacks was not buried in Ajijic, he was the first person to be buried in the Mezquitán cemetery in Guadalajara.

It is worth noting that Neill James and several of the foreigners mentioned in Dust on My Heart all attended the opening of Edythe (Edith) Wallachh Kidd’s artshow at the Villa Montecarlo in November 1944. Guests at that event included Miss Neill James, Mr and Mrs Jack Bennett; Nigel Stansbury Millett and his father; Mr Otto Butterlin and his daughter Rita; Mr Witter Bynner; Mr Charles Stigel; Dr and Mrs Charles Halmos; Miss Ann Medalie; and Sr. Herbert Johnson and his wife Georgette.

Angelita

p 274: “Angelita, a pretty copper-colored young widow, cook for the Heuer establishment.”

– ??

Dolores Navarro aka ‘Lola’

p 285, 293, 295-297: “my Spanish teacher, Dolores Navarro, a sixteen-year-old Spanish girl…”

– This may be the María Dolores Navarro (born in Tuxcueca in about 1927) who is recorded as marrying, at the age of 18, Juan José Pérez, a 24-year-old fisherman from Jocotepec, in Ajijic on 24 Jan 1945.

Sr. Pantoja

p 285: Dolores, quoted on the subject of bandits: “Pantoja who owns the bus line, was kidnapped…. His daughter-in-law ran for the Padre. She’s Maria, you know her, the nurse.”

– This is presumed to be Antonio Pantoja Castellanos (1928–2005), son of Ignacio Pantoja (1902-1932) and María Nieves Castellanos (1904-1995), though he would have been quite young at the time. Alternatively it may refer to his uncle, Ignacio’s older brother Antonio Pantoja Sr., who was born in about 1876.

Apolonia Flores and her children

p 291: “I have a cook with the poetic name of Apolonia Flores…. She is a widow, and her three children are called Elpidia, Xavier and Josefina,” aged 15, 9 and 11 respectively.

– Apolonia Márquez Hernández, the daughter of Braulio Márquez and Vicenta Hernández, was 23 years old when she married 24-year old farmhand Celedonio Flores in Ajijic on 15 April 1924. The couple’s first child, Delfino Flores Márquez, was born on 22 December 1926 and died at home (Ocampo #110) of malaria on 14 April 1936 at the age of 9. Elpidia, born in 1929, was 16 when she married 17-year-old J. Jesús Santa Cruz in Ajijic in 1948. Josefina is possibly the María Josefina Flores Márquez (recorded on an uncorroborated family tree online) born on 19 March 1933, who died in San Bernardino, California, on 19 January 2021. Nothing more is currently known about Xavier Flores Márquez, who must have been born in about 1935.

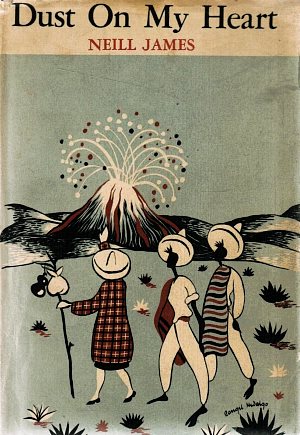

Dust jacket of Dust on my Heart (1946)

Sources:

- El Informador: 18 November 1944, 6.

- Neill James. 1946. Dust on My Heart. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Reprint edition by Lake Chapala Society, 1997.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via email or comments feature.