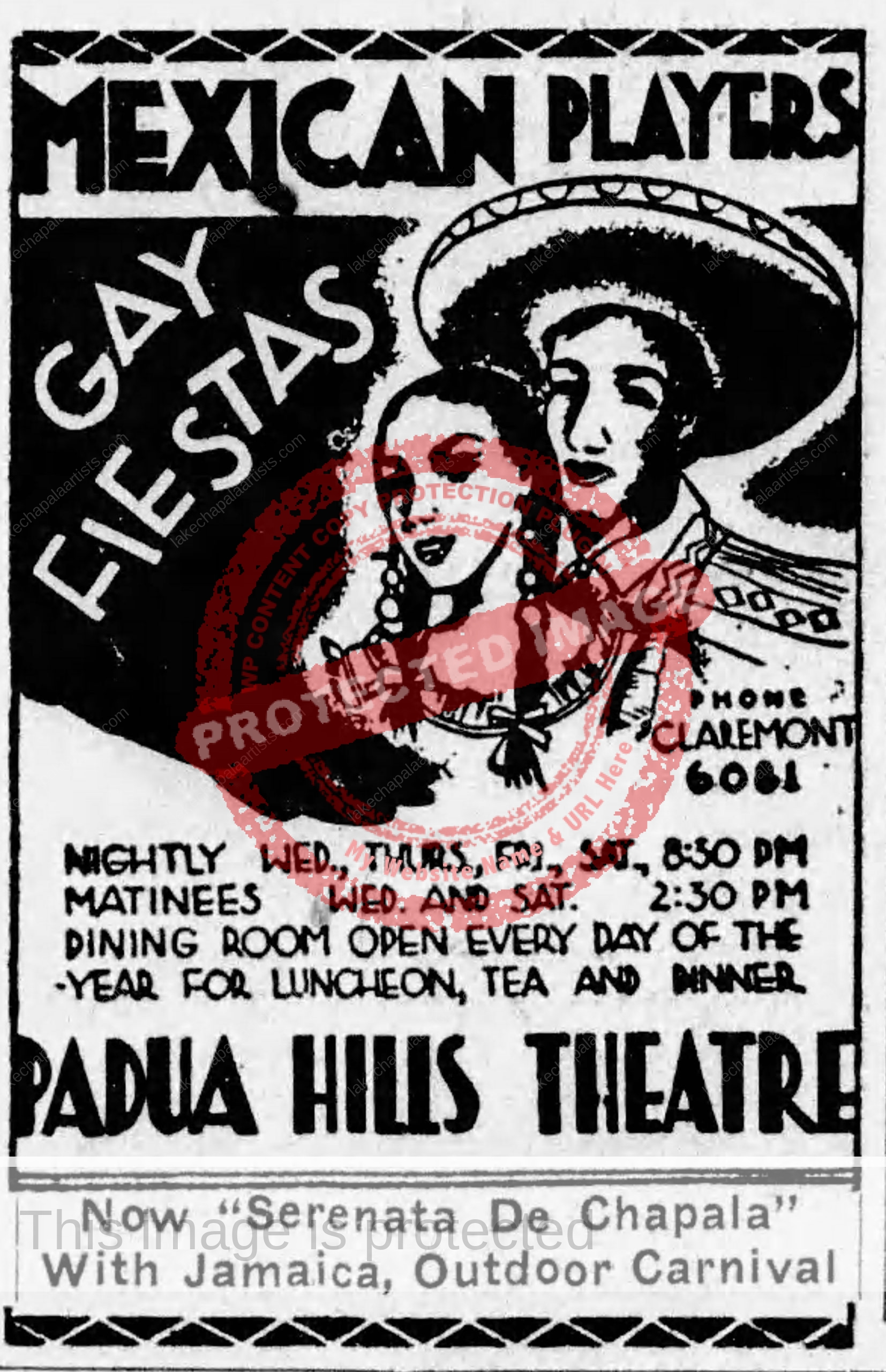

Serenata de Chapala was first performed at the Padua Hills Theatre, California, on 2 August 1939 and had a highly successful one-month run. This makes it the earliest Chapala-linked play I have so far come across! Unfortunately, it is highly unlikely that a script still exists, since its author and director, Charles Alvah Dickinson, was a strong proponent of improvisation.

Dickinson was born in Corona, California, on 26 December 1910 and died from a heart attack in Claremont, California, on 3 December 1950. He graduated from Pomona College in 1932 and gained a master’s degree from Caremont Graduate School in 1934, by which time he was already working with the Padua Hills Theatre, located three miles north of Claremont, a city on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County. In 1940, Dickinson married Kathryn Estelle Welch (1909-1984).

Dickinson’s 18 years with the Padua Hills Theatre was interrupted only by his service in the US Army from 1943 to 1945. At the theatre, he was the art and dance director of the Mexican Players, an acting group that was the mainstay of the Padua Hills Theatre, which began in the early 1930s and lasted until 1974.

Dickinson wrote more than 100 plays produced at Padua Hills, and acted in or directed many others. All the plays had close ties either to Mexico or to Mexico-California connections, and Dickinson’s in-depth knowledge of Mexico was ever-apparent. In 1936, for example, he took the part of an American entomologist in It rained in Ixtlán del Río, “a riotous comedy” about a bandit who tried to take advantage of a group of train passengers stranded in a crowded inn after their journey north was interrupted owing to a blockage on the railroad line.

The theatre, built in 1930, had struggled through the Great Depression. But Mr and Mrs Herman H Garner recognized the potential of the many young Mexican boys and girls who worked there and founded, in 1935, the Padua Institute. The institute arranged classes, some with guest teachers from Mexico, in music, dance, dramatics, languages and arts and crafts, all with the aim of promoting friendly relations between the US and Mexico.

Ad for “Serenata de Chapala (Redlands Daily Facts, 2 Aug 1939)

At the time Serenata de Chapala was running, the Mexican Players consisted of a group of about 30 young people of Mexican or Spanish Californian descent, some of whom were born in Mexico, and most of whom had lived in California for some time.

Serenata de Chapala was a rollicking romantic comedy in two acts. Performances were followed by a “Jamaica” or outdoor carnival of songs, dances and festive Mexican games. Presented in Spanish, Serenata de Chapala was about the serio-comic tribulations of a sextet of ardent young lovers. The “conversation of the play frequently introduces English, and the action is so arranged that it is easily followed by those who do not understand Spanish.” Chapala, the setting for the play, was described in publicity materials as “Mexico’s famed vacation resort.”

According to one review, “Serenata de Chapala told a merry and exciting story of how an Americanized Mexican lad unwittingly solved a romantic quadrangle through defying time-honored customs to give the señoritas a thrill.” Another reviewer wrote how “Serenading a señorita in Mexico at 4 o’clock in the morning is a hazardous pastime that may provoke a pistol barrage from an irate papa, to judge by the startling and hilarious climax of Serenata de Chapala.’”

“Serenata de Chapala” (Redlands Daily Facts, 14 Aug 1939)

The Padua Hills Theatre won national and international recognition as a unique cultural project, with the Stage magazine including them on their list of the ten best little theatre groups in the US. According to Wikipeda, Padua Hills Theatre was the longest running theater featuring Mexican-theme musicals in the US. The dinner theatre group called the “Mexican Players” lasted until 1974. Several former players continued their careers on stage; others, such as Natividad Vacío, made their name in movies.

The Padua Hills property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998, and is used today primarily for weddings and special events.

This website has many evocative images of the Padua Hills Theatre in its heyday.

Papers, flyers, photos and other material associated with Padua Hills Theatre are housed in a special collection at the Claremont Colleges Library.

Sources

- Anon. “‘Padua Hills’ – Unusual Institution.” Pacific Electric Magazine, August 1939, 3-4.

- Redlands Daily Facts: 25 Jul 1939; 2 Aug 1939; 14 Aug 1939; 23 Aug 1939.

- South Pasadena Review: 1 Sep 1939, 2.

- The Pomona Progress Bulletin: 12 Feb 1936, 5; 4 Dec 1950, 13.

- Santa Barbara News-Press: 4 Dec 1950, 3.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.