In Dust on my Heart (1946) Neill James relates several stories about “David Nixon, a New Orleans artist, and his wife June”, who were apparently seriously considering buying property at Lake Chapala until they were informed about various acts of violence that had been perpetrated there. The Nixons never did buy property in Ajijic and we know very little about their time at Lake Chapala, but David Nixon was a multi-talented musician and artist who deserves to be better-known.

David Sinclair Nixon was born 3 January 1904 in Bessemer, Alabama, and died in his long-time home of New Orleans in February 1973. His surname at birth was Burbage but became Nixon when his mother remarried.

Details of his early musical and artistic education remain a mystery though Nixon was apparently a former violin scholarship student of the Birmingham Music Club in Alabama.

After Nixon married June Prudhomme (a wealthy Louisiana widow and 14 years his senior who had been living in New York City), the couple established their home in Paris where Nixon developed his interest in modern art and continued his concert career. Travel records show that the couple crossed the Atlantic several times in the 1930s between Europe and the U.S.

Nixon studied the violin in Europe for more than a decade, taking classes in Paris, Rome and Berlin, and gave concerts in five countries. Among his teachers was the renowned Czech violinist Otakar Ševčík (1852–1934).

A February 1933 newspaper piece records that the Nixons, “of Paris, France” had been touring America over the previous winter and were currently staying in the St. Charles hotel in New Orleans.

In Europe, the Nixons became good friends with the poet and critic Ezra Pound and his long-time companion, the concert violinist and musicologist Olga Rudge. In the late 1930s, Pound supported Olga’s efforts as she and David Nixon sought to revive interest in the music of Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi. Rudge had studied many of Vivaldi’s original scores in Turin in 1936 in preparation for a series of concerts featuring some of Vivaldi’s lesser-known works. Nixon was also very familiar with many of the pieces. Following Nixon’s performance at a concert in homage to Antonio Vivaldi in Venice in October 1937, Pound wrote that “Nixon [is] trying hard to play well-beautiful tone, no technique, no solfège, and no bluff-the same state she [Olga Rudge] wuz in 15 years ago, but don’t know if he has her toughness.” [quoted in Conover]

With Pound’s help, Rudge and Nixon attempted to organize a Vivaldi Society in Venice. Though that venture proved unsuccessful, Rudge subsequently co-founded the Center for Vivaldi Studies at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana and edited a catalog of more than 300 of Vivaldi’s manuscripts that was published by the Accademia just before the start of the second world war.

By that time the Nixons were already safely back in New Orleans. A 1938 newspaper piece confirms that, following “a tour of Europe” and recognizing that war was inevitable, the Nixons had left France to live full-time in New Orleans. In September 1938, they acquired two properties in the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) – 529 Madison Street and 532-534 Dumaine Street – which shared a common boundary and would serve as their home, studio space and exhibition and performance venue.

The Nixons quickly became respected members of the city’s artistic-literary circle. Among their near neighbors was Lyle Saxon, a noteworthy local writer who was also a reporter on the staff of The Times-Picayune.

Nixon’s wide-ranging artistic talents had enabled him to become an accomplished puppeteer. His comical puppet shows for children, put on in a converted warehouse next to his home, became legendary. Nixon designed and created the puppets and the sets, wrote the stories and dialogue and manipulated the puppets, but the star of the show was often his cat, Selassie, who, suitably “costumed and combed”, would make a grand appearance, perform acrobatics and steal the show.

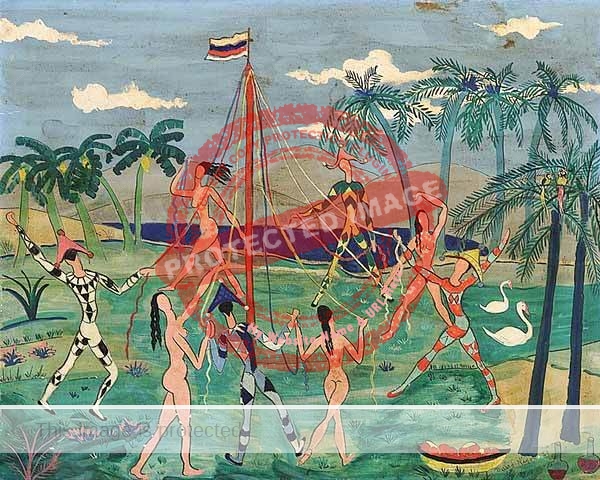

As a painter, Nixon became known for his colorful, often abstract works, and one of his oil paintings was awarded first prize at the 1943 New Orleans Spring Fiesta. In the 1940s Nixon opened the Little Gallery on Royal Street to showcase not only his own work but also that of many other artists. He later opened the David S. Nixon Art Foundation and Gallery on the Madison Street property belonging to his wife.

The Nixons’ visit to Ajijic came towards the end of the second world war and is described by Neill James in both her article for Modern Mexico (October 1945) and in Dust on my Heart (1946). The article includes a photograph captioned, “Neill James gave a party to show paintings made in Ajijic by David Nixon, fellow southerner from New Orleans”. Sadly, apart from this, little is known about David Nixon’s time in Ajijic.

In 1946, Nixon was invited to give a violin concert in support of the restoration of New Harmony, the historic Indiana town where Welsh industrialist Robert Owen tried to establish a Utopian community in the 1820s. Jane Blaffer Owen, wife of Robert Owen’s great-great-grandson, was the driving force behind the revitalization of New Harmony. In New Harmony, Indiana: Like a River, Not a Lake: A Memoir, she writes that:

“I invited David Nixon, a violinist from New Orleans, to share his considerable talents with the community. I rented Murphy Auditorium for a concert on Thursday, June 20, 1946, when children would be out of school and around the time when out family would customarily transfer from Houston to New Harmony. David, a recovering alcoholic, was addicted to sweets, particularly chocolate ice cream sodas, and could be found each morning at our local Ramsey pharmacy, which, in the 1940s and ’50s, was the town’s social center, its ice cream parlor and its dispensary. In the evenings he would play his violin on the streets of New Harmony for whoever wished to listen. His audience kept increasing.”

Despite Nixon going against the wishes of his host and playing only Bach and other eighteenth century music, the concert was a huge success.

During the latter decades of his life, Nixon seems to have become more focused on his painting. In January 1947 he was in a two-person show with Ukranian immigrant artist Ben-Zion at the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans. A reviewer in the Times-Picayune wrote that Nixon’s style was the more primitive and that the artist “paints because it pleases him and his work is entertaining with gay color and instinctive spotting.”

In 1948, the Nixons returned to Paris to live. Almost immediately, David started “The Chamber Music Society in Paris”. A short interview with Nixon appeared in the 11 February 1949 issue of Le Guide du Concert which featured his portrait on its cover.

In addition, according to Irma Sompayrac Willard in her profile of Nixon for The Times Picayune in August 1949, the musician-artist had:

discovered a charming medieval village in Provence which the mayor promptly gave to him on his promise to restore the roofs. He’ll do it, too, just as he restored that Madison st. house with its lovely patio. Now he’s busy forming committees, getting estimates, and lining up first residents for his ancient French village. He talks of summer music festivals there, of puppet shows and exhibitions and maybe the possibility of getting New Orleans to adopt this unbelievably beautiful little town with its apple blossom and hilltop church.”

Just how much of this plan became reality is unknown!

By the late 1950s, the Nixons were back in the U.S., where they lived for a time in Carmel, California. When asked about his one-man show of paintings at the Carmel Craft Studios in May 1957, Nixon said that the gallery was similar to the Arts and Crafts Gallery in New Orleans and added that his next major show was due to open in September at the Leveaugh Gallery in San Francisco. He and his wife planned to return to New Orleans in 1959 and would reopen their Madison Street art gallery. The Nixons did indeed return and reopened the gallery on premises that had been rented since 1951 by the Gallery Circle theater.

By the late 1950s, the Nixons were back in the U.S., where they lived for a time in Carmel, California. When asked about his one-man show of paintings at the Carmel Craft Studios in May 1957, Nixon said that the gallery was similar to the Arts and Crafts Gallery in New Orleans and added that his next major show was due to open in September at the Leveaugh Gallery in San Francisco. He and his wife planned to return to New Orleans in 1959 and would reopen their Madison Street art gallery. The Nixons did indeed return and reopened the gallery on premises that had been rented since 1951 by the Gallery Circle theater.

The building the theater moved to was destroyed by fire the following year. Theater organizers approached Nixon to see if he would allow them to rent their former home again but Nixon declined, saying that he and his wife were definitely home from Europe for good.

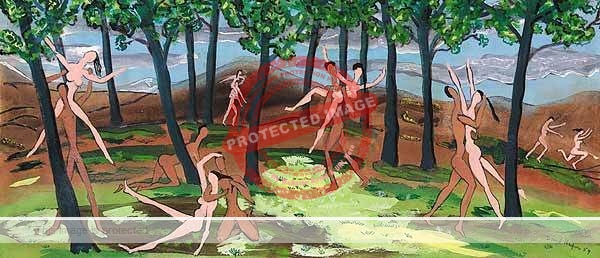

June Nixon passed away in about 1963. That same year David Nixon held another one-person show, at 542 Chartres in the French Quarter. A review of the show maintained that “to really appreciate it you need a certain elfish sense of humor”, and that it helped “to have ears that are tuned in to the pipes of Pan” since Nixon’s elongated nymphs “gambol, pipe and play through the paintings.”

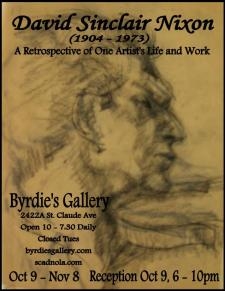

During his lifetime Nixon exhibited his art in four countries – the U.S., Mexico, France and Italy – with noteworthy showings in Paris, Mexico City, Rome, and at the Galeria Neuf in New York. A major posthumous retrospective of Nixon’s work, “David Sinclair Nixon (1904-1973): A retrospective of one artist’s work” was held at Byrdie’s Gallery in New Orleans in October 2010.

Note:

- The original version of this post was published on 17 September 2015.

Sources:

- Anniston Star. 1943. “David Nixon Honored at New Orleans Fiesta.” Anniston Star (Anniston, Alabama), 30 May 1943, p 6.

- Anne Conover. 2008. Olga Rudge & Ezra Pound. Yale University Press.

- Neill James. 1945. “I live in Ajijic”, in Modern Mexico, October 1945.

- Neill James. 1946. Dust on my Heart.

- Jane Blaffer Owen. 2015. New Harmony, Indiana: Like a River, Not a Lake: A Memoir. Indiana University Press.

- Olga A. Rudge. 1939. Vivaldi, note e documenti sulla vita e sulle opere. Siena: Academia Musicale Chigiana.

- Irma Sompayrac Willard. 1949. “French Quarter to French Capital”, Times-Picayune 14 August 1949, p 154.

- Times-Picayune – 26 Feb 1933, p 23; 9 October 1938, p 67; 6 January 1947, p 14; 19 May 1957, p 37; 22 November 1959, p 57; 4 August 1963, p 53.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).