In June 1969, three young Jocotepec-based artists – John Brandi, Tom Brudenell, and Shaw – joined forces to stage a Cocktail Party “happening” [1].

What exactly did the artists have in mind?

According to Shaw, the prime instigator of the event, the purpose of the Chula Vista happening, or “performance”, was to challenge the artistic status quo in the Lake Chapala area. It was intended to be deliberately provocative, hence the choice of venue being Chula Vista, the first retirement real estate development in the area. The idea was to target American retirees, many of whom, Shaw felt, were only there because land, building materials and labor were far cheaper than in the States. Though they chose to live there, many of them “hated the people who worked for them”: the campesinos, maids and gardeners.

Brudenell’s motives were somewhat different. He wrote at the time that all three artists had independently come to believe that observers needed to do more than simply observe, they needed to be drawn into the artists’ work. The artists’ terminology differed but shared ample common ground: Brudenell’s idea of “Hypnosis” was essentially the same as Brandi’s “Participation” and Shaw’s “Ritual”. In consequence, Brudenell (who prefers to call the event a “Myth-Mass”) says that this “ritual” event was aimed at creating an atmosphere that might stimulate the audience to venture beyond passive viewing.

All three artists intended this to be a trial run for a series of later “Myth-Mass” events targeted at diverse groups and communities, from small-town America to the Oakland chapter of the Hell’s Angels. (For a variety of reasons, these plans were never realized).

Where, when, and how?

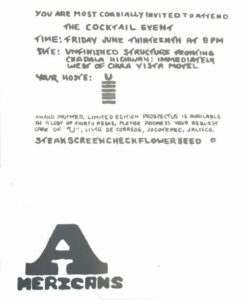

The Chula Vista Cocktail Party happening was held in a partly-completed building alongside the Chula Vista motel, mid-way between Ajijic and Chapala, and took place, perhaps appropriately, on Friday 13th June 1969.

Whatever the precise motivation, this seems to have been Mexico’s first ever artistic happening, occurring a few years after the earliest happenings in the U.S., but at about the same time as the first to be held in Canada.

A couple of weeks prior to the event, the three artists spent three or four days in the Chula Vista area, interviewing residents, gathering ideas and taking photos of the people, workers and area. Some of this material became an integral part of the happening.

The three artists made somewhat different contributions to the overall event. John Brandi contributed drawings, milagros (folk charms) and poems. Brudenell contributed paintings and set up stations (echoing rituals of a mass) with pebbles, bowls, slides and smell-bulbs (olfactory triggers for the recall of past experiences). Shaw made prints of symbols and constructed 3-D scenes involving large transparent plastic symbol forms, stuffed with various figures (many of them dolls) which could be walked through and around.

Brudenell’s journal entries from the months prior to the Chula Vista event offer some fascinating insights into his thinking about how the 1969 Chula Vista event should be organized. The three key elements that Brudenell conceptualized were Setting, Symbols and Ritual.

He saw the Setting as preparatory, but essential to establish “anticipatory impulses”. The Symbols, devices for Affect, needed to “create a following,” while the elements associated with Ritual/Hypnosis/Participation [RHP) needed to grab and hold people’s attention:

“Setting must be familiar stimuli but must prepare O [Observer] for unfamiliar or unacceptable stimuli.”

“Symbols must evoke following or they will become decoration.”

“RHP must be operable in presentation of symbols and can most easily be applied using the mechanisms of the Setting.”.

For this multi-room event to succeed, Brudenell was convinced that the links between elements must be stressed:

“For example, magazine on table in Setting could be photographed on table exactly as it is. The photo would serve (in the Symbol room) as a link between the familiar object and the associated symbolism.”

[The overall purpose is] “not a matter of introducing the NEW (i.e. blowing minds). It is the matter of EXTENDING the ritual beyond the point of its freezing – that point beyond which the People do not wish (fear) to go.”

In autobiographical notes written later for the Emily Carr College Outreach program, Brudenell summarized his own contribution as searching for “universes beyond the limits of the biologist’s microscope and the astronomer’s telescope.”

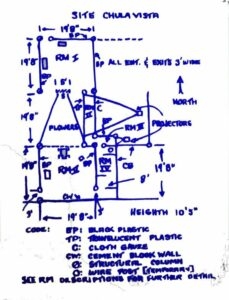

The invitations (see first image, click to enlarge) said that the event was hosted by “U” (underlined several times, perhaps alluding to an I-Ching symbol, used thousands of years earlier, for opening the mind to receiving answers to fundamental questions). Shaw prepared some unique hand-printed prospectuses, priced at $30 pesos and available on request.

The artists’ plan, by Shaw, for the site was positively architectural, and it was organized so as to ritualize the event, with well-defined steps and symbols, akin to a religious Mass:

The cocktail party was the ritual. The four “ritual objects” or “symbol objects” for the event were steak, screen, check, flower-seed. These were “transition” objects “for leading the viewer deeper into underlying or new perspectives embodied in each symbol. This well-known “symbol search” method has been used in Expressive therapy and art to facilitate an individual’s “inward” awareness, to bring the unconscious into the conscious.”

It was a walk-through event, in which visitors were first offered a cocktail and then ushered along a route through various rooms to view, be exposed to, or take part, in a variety of artistic stimuli. The “manual” written by the artists set out specific requirements for how the various slides, printed images, sense-challenging objects, and so on, should be presented.

It was a walk-through event, in which visitors were first offered a cocktail and then ushered along a route through various rooms to view, be exposed to, or take part, in a variety of artistic stimuli. The “manual” written by the artists set out specific requirements for how the various slides, printed images, sense-challenging objects, and so on, should be presented.

All visitors were given an “Instructions” sheet to help explain what they needed to do in order to appreciate the happening to the fullest:

The set-up plan for the first room at the entrance looked like this:

The set-up plan for the first room at the entrance looked like this:

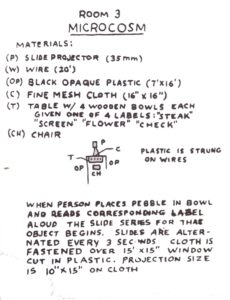

The set-up plan for Room 3 involved slides projected through filters and visitors were asked to place their pebble and read a label before the relevant slides began to be shown:

The set-up plan for Room 3 involved slides projected through filters and visitors were asked to place their pebble and read a label before the relevant slides began to be shown:

Room 5 was the show-stopper. Visitors had earlier watched a short movie and studied various still photos. Now they were confronted with sights ranging from a vintage 1910 Ford truck, complete with campesino driver sounding the vehicle’s horn every few minutes, to an indigenous woman in one corner preparing hand-made tortillas over a wood fire.

Room 5 was the show-stopper. Visitors had earlier watched a short movie and studied various still photos. Now they were confronted with sights ranging from a vintage 1910 Ford truck, complete with campesino driver sounding the vehicle’s horn every few minutes, to an indigenous woman in one corner preparing hand-made tortillas over a wood fire.

Was it a success?

Shaw recalls that the event was attended by about 150 people, 90% of whom clearly enjoyed it. He professes himself particularly delighted that the campesinos understood it, and that Mexicans loved it..

He says that the powerful ponche served at the event certainly loosened the audience’s tongues, to the point where one particular American became overly aggressive and had to be repeatedly told to quieten down by other visitors. A few weeks later, when Shaw visited a Mexican official in Guadalajara, the official told him that his office had received a phone call from someone at the U.S. consulate asking that Shaw and his fellow artists be kicked out of the country. The official then laughed and said “That will never happen!” since the event had clearly been enjoyed by everyone else, especially those Mexicans present.

On the other hand, Brudenell doubted that it had been a success. He felt that most of the audience misinterpreted the artists’ intentions, and mistakenly thought they were attending a “light-show” or a “mean-spirited [artistic] ambush”.

His notes, made immediately after the 1969 Chula Vista Myth-Mass, suggest how future events could be improved:

“Person-to-person relationship was neglected. Apparent feeling that the “machine” would do it all was primary cause of failure. Unprepared hostesses did not provide guidance for the audience.”

“ORIENTATION is MOST important. Without knowing the ritual beforehand the audience cannot be expected to focus attention on the content of the ritual.”

“Some people felt the rite to be an unsophisticated light-show. The mere use of electricity gives hints of “mind blowing light-show.” Need to avoid being categorized as “light show” – must eliminate electricity in every possible way. Need to emphasize tactile ritual setting – primitiveness.”

What is the event’s significance?

As both Shaw and Brudenell stressed to me, the Chula Vista “Myth-Mass” needs to be viewed against the backdrop of the 1960s. The happening took place at a time when the U.S. had become extremely divided, on account of events such as the Vietnam War, the War on Drugs, and the Civil Rights Movement. It also took place only a year after the killing of up to 300 students in the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City. In their various ways, all three artists were caught up in the “Art imitates life” revolution of the 1960s.

Soon after the Chula Vista event, the trio staged two more happenings, both in Guadalajara, but they abandoned plans for similar events in the U.S. Within a year, Brudenell and Brandi had both left Jocotepec and headed north, though Shaw remained in Jocotepec for several more years.

The event also holds significance because it was, almost certainly, Mexico’s first ever artistic happening. It certainly challenged the local community to engage more with local artists.

The entire approach was clearly meant to be provocative, and might almost be considered presumptuous. This particular happening was almost guaranteed to alienate many of those witnessing it! Fortunately for the artists who would follow, it had no obvious adverse impact on the region’s art community.

Lake Chapala had a flourishing artistic and literary community during the 1960s and early 1970s. The area had attracted a good number of talented young artists and writers from Europe and the U.S. This 1969 Chula Vista event was held right in the middle of this particularly fecund period of artistic experimentation and exploration. By the mid-1970s, many of the artists had moved on, taking their experiences from Mexico to look for new challenges and inspiration elsewhere. As we have seen in this series, many would soon became well-recognized artists in their new homes.

The artistic vacuum they left behind at Lake Chapala took some time to fill. It created opportunities for other artists to achieve some degree of commercial success. This was especially true for those who focused on producing art that matched the tastes of the growing tide of incomers moving into the many new residential developments springing up along the lakeshore.

- – – –

[1] Footnote: While a “happening” has no precise definition, Wikipedia calls it “a performance, event or situation meant to be considered art, usually as performance art. Happenings occur anywhere and are often multi-disciplinary, with a nonlinear narrative and the active participation of the audience. Key elements of happenings are planned but artists sometimes retain room for improvisation.” –

My sincere thanks to both Don Shaw and Tom Brudenell for commenting on an early draft of this piece, for discussing their memories of this event with me, and for allowing me access to many documents and artworks from their private collections. Unfortunately, my attempts to contact John Brandi, the third artist, for his perspectives, have so far been unsuccessful.

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

I know this is an old post but I believe i have one of Shaws pieces from this event. It’s titled Mask signed shaw 1969 edition of 10

Fletch: Nothing old about the post! How did you come by it, and are you willing to share a photo or photos of the mask, please? If so, please use this email. Thanks!