In an earlier post, we looked at the multiple achievements of Emma-Lindsay Squier, an extraordinary woman who visited Guadalajara and Lake Chapala in 1926.

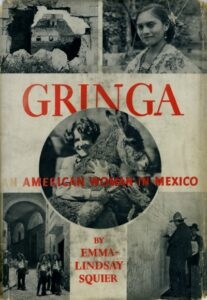

In this post we take a closer look at just how Squier described her visits to Lake Chapala and Jocotepec in her autobiographical Gringa: An American Woman in Mexico (1934).

Her initial impressions of Lake Chapala were, frankly, not that positive:

“About twenty miles east (sic) of Guadalajara is the famous Lake Chapala. It is by way of being the Mexican Riviera; one which lacks, however, the Continental touch. It tries hard to be sophisticated, but I did not find the purple and pink stucco castles of the millionaires either interesting or in good taste. Mexico is at her best when she caps herself with red tile, bougainvillea vines over her painted adobe panniers, and smilingly challenges the world to produce anything more pictorial.” (Gringa, 145)

However, she was fascinated by the possibility that the Aztecs had lingered at Lake Chapala for several hundreds of years, during their migratory wanderings:

“Today, the blue waters of the lake and burial mounds on the the surrounding hills are constantly yielding up primitive, distorted little clay images that are thought to be mementos of that far-gone time. The Indians say that these small people of barro (clay) are those of the Aztec tribe who would not desert Chapala, and for their disobedience were turned into soulless effigies. They say, too, that the fireflies one sees at night, drifting up from the marshy shores in clouds of golden stars, are the spirits of those repentant ones who are belatedly trying to follow their kinsmen to glories that have long been swallowed up in the tragedies of the past.” (Gringa, 145-146)”

From Chapala, she was then driven by Dr. William Walker to Jocotepec:

“We drove from the village of Chapala along a narrow sandy road that follows the lake. Now and then through the interlaced greenery of trees and shrubbery we could see long primitive fishing boats scooped out of logs propelled by triangular orange-colored sails, skimming across the blue water. The smell of nets drying on the beach mingled with the fragrance of lime blossoms. On the other side of the road, in fields, bounded by fences made of piled stones, small but powerful-looking cattle grazed, and white-garmented peons dozed in the shade of coral-flowered tavachin (sic) trees.”

The farther we drew away from the town of Chapala with its rococo castles and its air of pseudo-sophistication, the closer we came to a Mexico unspoiled, untainted by self-consciousness.

And when we bumped along a cobblestoned road that led to the plaza of Jocotepec, a wave of color and movement and music engulfed us. It was if we stepped out of the twentieth century into the life of a hundred years ago.” (Gringa, 146)

They arrived during a fiesta and she describes the people thronging the plaza:

“… the central square was an almost compact mass of peons in freshly white garments, shirts that were stiff with starch, and long, wide cotton trousers that had been pleated in diagonal lozenges by the patient application of heavy charcoal-heated irons.

The sombreros they wore lacked the high crowns I had seen elsewhere. But the brims made up for the lack of height. They were tremendously wide, curved upward at the edges just the least bit, and two long black cords came down from the shallow-crowned hat and held it under the owner’s chin or dangled down the back of his neck–al gusto.

Few of them wore shoes. Their brown feet were encased in finely woven sandals. But every mother’s son of them in that bobbing, undulating throng was carrying a sarape over his shoulder, the kind you see only in this remote Indian village, one with a dark background of well-carded wool and a woven border of vivid flowers. The boca (mouth) is ornamented thus as well. When the wide opening is slipped over the owner’s head, he is wearing a fringed brown cloak, decorated with flowers, so closely woven that the tropical rain can scarcely seep through.” (Gringa, 147).

Squier goes on to describe the mariachi bands, and being invited to a local bullfight by the mayor – presidente – of the town, an invitation she was unable to pass up. Fortunately, it turned out to be a bloodless bullfight in which the bulls were not killed.

Some time later, when she was listening to a mariachi band in Mexico City with her husband John Ransome Bransby, Squier was delighted to see that some members of the group were wearing sarapes identical in design to those she had seen in Jocotepec. Sure enough, several of the band’s members were indeed from that village on Lake Chapala.

Source:

- Emma-Lindsay Squier. 1934. Gringa: An American Woman in Mexico (Houghton Mifflin Co.)

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).