Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons (1875-1941) was a woman way ahead of her time. Variously described as a “relentlessly modern woman”, “a pioneering feminist” and “eminent anthropologist”, she was all of these and so much more.

Parsons, born to a wealthy family in New York City on 27 November 1875, became one of America’s foremost anthropologists, but also made significant contributions as a sociologist and folklorist. She is best known for pioneering work among the Native American tribes in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico, including the Tewa and Hopi.

Parsons, born to a wealthy family in New York City on 27 November 1875, became one of America’s foremost anthropologists, but also made significant contributions as a sociologist and folklorist. She is best known for pioneering work among the Native American tribes in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico, including the Tewa and Hopi.

Parsons visited Mexico numerous times, and had spent extended periods in Mexico prior to her visit to Chapala in December 1932. On that occasion, she spent at least 10 days there; it is unclear if she revisited the lake area at any point after that.

She gained her bachelor’s degree from Barnard College in 1896, and then switched to Columbia University to study history and sociology for her master’s degree (1897) and Ph.D. (1899).

The following year, on 1 September 1900, she married lawyer and future Republican congressman Herbert Parsons, a political ally of President Roosevelt, in Newport, Rhode Island. She lectured in sociology at Barnard from 1902 to 1905, resigning to accompany her husband to Washington.

Her first book, The Family (1906) was a feminist tract founded on sociological research and analysis. Its discussion of trial marriage became both popular and notorious, leading Parsons to adopt the pseudonym “John Main” for her next two books: Religious Chastity (1913) and The Old Fashioned Woman (1913). She reverted to her own name for Fear and Conventionality (1914), Social Freedom (1915) and Social Rule (1916).

In 1919, she helped found The New School for Social Research in New York City and became a lecturer there. In that same year, Mabel Dodge Sterne (later Mabel Luhan), a wealthy American patron of the arts, moved to Taos, with her then husband Maurice, to start a literary colony there. Luhan sponsored D.H. Lawrence‘s initial visit to Taos in 1922-23 and helped Parsons with her research into local Native American culture and beliefs.

In 1919, she helped found The New School for Social Research in New York City and became a lecturer there. In that same year, Mabel Dodge Sterne (later Mabel Luhan), a wealthy American patron of the arts, moved to Taos, with her then husband Maurice, to start a literary colony there. Luhan sponsored D.H. Lawrence‘s initial visit to Taos in 1922-23 and helped Parsons with her research into local Native American culture and beliefs.

For more than 25 years, Parsons conducted methodical fieldwork and collected a vast amount of data from the Caribbean, U.S., Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, much of which she would eventually synthesize into major academic works. These include the widely acclaimed works about Zapotec Indians in Mexico: Mitla: Town of the Souls (1936), Native Americans in Pueblo Indian Religion(2 volumes, 1939), and Andean cultures in Peguche, Canton of Otavalo (1945).

She also published a number of works on West Indian and African American folklore, including Folk-Tales of Andros Island, Bahamas (1918); Folk-Lore from the Cape Verde Islands (1923); Folk-Lore of the Sea Islands, South Carolina (1923); and Folk-Lore of the Antilles, French and English (3 volumes, 1933–43).

Parsons served as associate editor for The Journal of American Folklore (1918-1941), president of the American Folklore Society (1919-1920) and president of the American Ethnological Society (1923-1925). At the time of her death, she had just been elected the first female president of the American Anthropological Association (1941).

Parsons’ visit to Lake Chapala in December 1932 is noteworthy for several reasons.

She was traveling with fellow anthropologist Ralph Beals (1901-1985). They had been working with the Cora and Huichol Indians at Tepic, Nayarit, and were on their way south towards Oaxaca. [Parsons, incidentally, was responsible for introducing Beals, who founded the anthropology and sociology departments at UCLA, to her anthropological fieldwork techniques. He employed similar techniques to great effect when he built on Parsons’ prior work at Mitla, and expanded it into his 1975 work, The Peasant Marketing System of Oaxaca, Mexico.]

Parsons and Beals arrived in Guadalajara by train from Tepic, but Parsons decided that the city had little to offer ethnologically, so they chartered a car and drove to Chapala.

“There they settled into the inn, where Beals’s room looked out across an arm of the lake to a tree-embowered house where D. H. Lawrence had stayed a few years before.” “I have never been in such an enchanting place in my life,” Beals wrote Dorothy [his wife]. “If I had to pick just one place to go with you I’d certainly pick this.” (quoted in Deacon)

Parsons had heard that the villages around the lake performed an interesting version of the dance called La Conquista (The Conquest) in the multi-day celebrations for 12 December, Guadalupe Day. She and Beals took a boat to Ajijic on 15 December to watch events unfold, discovering that there were so few other spectators that the procession and dances were clearly held for the participants’ own pleasure. Parsons was not favorably impressed by Lake Chapala’s small villages, calling them “unattractive, as squalid as Spanish towns”, and concluding that, “They must have been settled by Spanish fishermen, and god knows what became of the Zacateca population.” [quoted in Deacon]

They spent ten days at Lake Chapala, during which time, according to Zumwalt, Parsons worked on an early draft of Pueblo Indian Religion.

Leaving Chapala, they took a two-hour launch ride to Ocotlán, before catching the train to Mexico City, where they arrived just in time for the social whirlwind of Christmas.

Several years later, Parsons published a short paper entitled “Some Mexican Idolos in Folklore”, in the May 1937 issue of The Scientific Monthly. This article included several mentions of Lake Chapala, with Parsons casting doubt on the authenticity of the stone ídolos (idols) collected there by some previous anthropologists and ethnographers.

Parsons describes how ever since the 1890s, there has been,

“at this little Lakeside resort a traffic in the ídolos which have been washed up from the lake or dug up in the hills back of town, in ancient Indian cemeteries, or faked by the townspeople. An English lady who visited Chapala thirty-nine years ago quotes Mr. Crow as saying that the ídolos sold Lumholtz were faked, information that the somewhat malicious Mr. Crow did not impart to the ethnologist.”

While Parsons is not sure what became of Lumholtz’s collection, she says that the items collected at about the same time by Frederick Starr, and which are now in the Peabody Museum in Cambridge (Harvard University), are definitely genuine and not faked.

The “Mr. Crow” referred to by Parsons is Septimus Crowe (1842-1903). [For more about Septimus Crowe and about the Lumholtz and Starr trips to Lake Chapala in the 1890s, see my Lake Chapala Through The Ages, an Anthology of Travellers’ Tales.]

One real mystery stemming from Parsons’ description above is the identity of the “English lady who visited Chapala thirty-nine years ago.” Just who was she? Clearly, she must have visited Chapala in the period 1895-1898. There seem to be two likely candidates. The first is The Honorable Selina Maud Pauncefote, daughter of the British Ambassador in Washington, who returned from a trip to Mexico in March 1896, coincidentally on the same train as Lumholtz. The only known article by Pauncefote relating to Chapala is “Chapala the Beautiful”, published in Harper’s Bazar (1900). It is very likely that she may met and knew Crowe, since he had been a British Vice Consul in Norway, though she makes no mention of him in her article. The second candidate is Adela Breton, a British artist who visited (and painted) several archaeological sites in Mexico in the years after 1894, though her connection to Septimus Crowe is less clear.

The bulk of Parsons’ paper is devoted to her argument that the Lake Chapala miniatures are prayer-images, similar to those used in Oaxaca and elsewhere:

“All the Chapala offerings are either perforated or of a form to which string could be tied. They may have been hung on a stick, a prayer-stick, just as the Huichol Indians hang their miniature prayer-images to-day.”

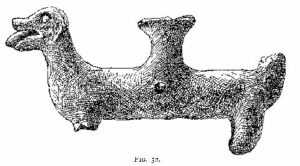

Parsons describes how some figurines of a dog (she actually had a faked copy of such a dog on her table at Chapala) had something in their mouth and a container on their back. The container, Parsons argues, was to carry humans across the river after death. Pet-lovers everywhere will rejoice to learn that:

“The dog ferryman belief is that if you treat dogs well a dog will carry you across the big river you have to cross in your journey after death… but if you have maltreated dogs, beating them or refusing them food, you will be left stranded on the river. The river dogs are black for an Indian, and the Zapotecs, and white for a Spaniard; white dogs will not carry an Indian lest they soil their coats – unless you have a piece of soap with you and promise to wash your ferryman on the other side. The burden or carrying basket of the Chapala Lake region, the ancient basket carried in the ancient way, by tumpline, is the exact shape of the object on the back of the dog figurine, narrow and deep and flaring toward the top.”

On 19 December 1941, after an amazingly productive and full life, Elsie Crews Parsons left New York City and was ferried across the river into the after-world.

Sources:

- Desley Deacon. 1999. Elsie Clews Parsons: Inventing Modern Life (Univ. of Chicago Press)

- Catherine Lavender. 1998. Elsie Clews Parsons, The Journal of a Feminist (accessed 16 Dec 2015)

- Elsie Clews Parsons. 1937. “Some Mexican Idolos in Folklore”, The Scientific Monthly, May 1937.

- Frederick Starr. 1897. The Little Pottery Objects of Lake Chapala. (Univ. of Chicago)

- Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt. 1992. Wealth and Rebellion: Elsie Clews Parsons, anthropologist and folklorist. 360 pages.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).