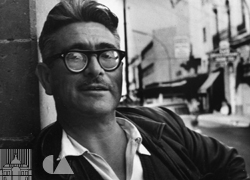

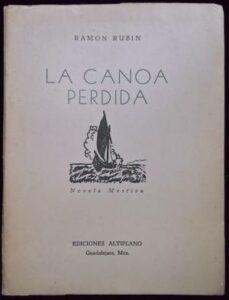

Mexican author Ramón Rubín Rivas (1912-2000) wrote a novel set at Lake Chapala: La canoa perdida: Novela mestiza. He wrote more than a dozen novels and some 500 short stories over a lengthy career and this work, first published in 1951, is considered one of his finest, though it has never been translated into English.

Rubín was a particularly keen observer of the way of life, customs and beliefs of Mexico’s many indigenous groups. His writing is based on extensive travels throughout the country and prolonged periods of residence with several distinct indigenous groups including the Cora/Huichol in Nayarit and Jalisco, the Tarahumara (raramuri) in the Copper Canyon region of Chihuahua, and the Tzotzil in Chiapas. His novel about Lake Chapala, which we will look at in more detail in a future post, is the story of an indigenous fisherman who wants to acquire a canoe, set against the background of a lake facing serious problems. During the 1950s, Rubín was an ardent campaigner for the protection of the lake when drought and overuse threatened its very existence.

The early history of Rubín’s life is hazy. His “official” biography states that he was born to Spanish immigrant parents in Mazatlán, Sinaloa, on 11 June 1912, and that the family moved to Spain when Rubín was two years old. However, some researchers have found evidence suggesting that he was actually born on that date in San Vicente de la Barquera in northern Spain, and subsequently “adopted” Mazatlán as his birthplace as he became known as a Mexican writer. Rubín would apparently respond to questions about his birthplace by saying that his only source of information had been his parents, and they had said he was born in Mazatlán. The lack of a Mexican birth certificate is not surprising given that the public records in many parts of Mexico were destroyed during the early years of the Mexican Revolution, which erupted in 1910.

Wherever he was born, Rubín attended school in Spain until 1929 when, at the age of sixteen, he relocated to Mazatlán in Mexico. It was while taking typing classes in Mazatlán (as a means of earning a living) that he wrote his first stories, allegedly because he was sitting too far from the blackboard to copy what the teacher wrote as practice exercises. The teacher agreed that he could write whatever he wanted, provided there were no typing errors, and Rubín’s literary career was under way.

Working as a salesperson, Rubín traveled widely in Mexico. When he settled for a time in Mexico City, he had several short stories, based on his travels and experiences, published in Revista de Revistas. He later became a regular contributor to newspapers, especially to El Informador and El Occidental. Rubín’s direct approach to narrating stories owes much to his childhood, when he was entranced by Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and by the adventure novels of Emilio Salgari.

In the Spanish Civil War (1938), Rubín enlisted as a merchant seaman on the side of the Republicans. While not formally a member of the International Brigades, he took a cargo of arms and ammunition to Spain and was lucky to escape alive. Franco’s forces dropped 72 bombs on his ship, none of which hit their intended target.

Rubín enjoyed a measure of literary success in 1942 with the publication of the first of an eventual five volumes of short stories, all entitled Cuentos mestizos (“Mestizo tales”). Later short story collections include Diez burbujas en el mar, sarta de cuentos salobres (1949), two volumes of Cuentos de indios (1954 y 1958), Los rezagados (1983), Navegantes sin ruta: relatos de mar y puerto (1983) and Cuentos de la ciudad (1991).

Rubín enjoyed a measure of literary success in 1942 with the publication of the first of an eventual five volumes of short stories, all entitled Cuentos mestizos (“Mestizo tales”). Later short story collections include Diez burbujas en el mar, sarta de cuentos salobres (1949), two volumes of Cuentos de indios (1954 y 1958), Los rezagados (1983), Navegantes sin ruta: relatos de mar y puerto (1983) and Cuentos de la ciudad (1991).

Rubín had traveled to Chiapas for the first time and lived among the Tzotzil in 1938. He put this knowledge to good use in his first novel, El callado dolor de los tzotziles {“The silent pain of the Tzotzil”) (1949). Literary critics consider this to be a seminal portrayal of Mexico’s indigenous peoples. The novel goes far beyond mere description or adulation of indigenous lifestyles and is a genuine drama about the intolerance of an indigenous community towards a couple who are unable to have children. In line with tribal tradition, the woman is banished to the mountains, the man leaves the community to live for a time among the mestizos. When he returns, his mental state altered by his experiences, he spirals downwards and seeks refuge in alcohol.

In a later indigenous novel, entitled La bruma lo vuelve azul (“The smoke turns blue”) (1954), the main character is a Huichol Indian named Kanayame who is rejected by his father, stripped of his indigenous roots in a government school, and turns to banditry. Rubín’s other indigenous novels include El canto de la grilla (1952), La sombra del techincuagüe (1955) and Cuando el táguaro agoniza (1960).

In addition, Rubín wrote the novels La loca (1949), La canoa perdida (1951), El seno de la esperanza (1960) and Donde mi sombra se espanta (1964). Some of his work has been translated (into English, German French, Russian and Italian) and several stories have been adapted for the stage. Rubín also wrote a short autobiography – Rubinescas – and several screenplays, none of which was ever made into a film, though Hugo Argüelles’s 1965 film Los cuervos están de luto is a plagarized version of Rubín’s original story “El duelo”.

Given that Rubín’s books have a wide appeal – cited as valuable sources of information about people and landscapes by anthropologists, biologists, sociologists and geographers – and were acclaimed by famous contemporaries, including his good friend Juan Rulfo, and literary historians, including Emmanuel Carballo who saw fit to include him in his Protagonistas de la literatura mexicana – why is it that Rubín is not much better known?

First, many of his books had small print runs, and were often self-financed, not the work of major publishers. Many of his books are, therefore, very difficult to find.

Second, Rubín was very much an individualist and neither living in Mexico City nor a member of any mainstream literary group.

Third, according to the author himself, his public disagreements with another famous Jalisco novelist, Agustín Yáñez, who served as Governor of Jalisco during the crisis affecting Lake Chapala in the 1950s, led to him being denied support by any of Yáñez’s numerous friends. Rubín was a vigorous opponent, on ecological grounds, of many of the “development” (drainage) schemes proposed during Yáñez’s administration.

Indeed, when he was chosen as the recipient of the Jalisco Prize in 1954, he declined to accept it on both intellectual and moral grounds, not wanting anything to do with the Yáñez administration which he believed had failed to do enough to protect Lake Chapala. (He was eventually awarded the Prize in 1997).

Rubín was proud of the fact that his work was based on travel and first-hand research, and did not derive from library sources or from his imagination while sitting at his desk. His writing shows that action and plot are more important to him than relaying introspective thoughts or feelings. However, he disliked the suggestion, sometimes made by literary critics, that he was Mexico’s Hemingway.

Rubín lived the bulk of his creative years (1940-1970) in Guadalajara. He taught at the University of Guadalajara and owned two small shoe manufacturing companies in Jalisco, both of which he eventually gave to his employees. In the early 1970s, he spent three years in Autlán, in the southern part of the state, before moving to San Miguel Cuyutlán, near Tlajomulco, for a decade. He then lived in a seniors’ home in Guadalajara for two years. Notwithstanding the many websites that claim he died the year before, Ramón Rubín Rivas died in Guadalajara on 25 May 2000.

Rubín did not win as many awards as might be expected from the quality and originality of his work, but he was awarded the Sinaloa Prize for Arts and Sciences in 1996 and the Jalisco Literary Prize in 1997. Prior to either of those awards, he had been recognized in the U.S. by the award from the New Mexico Book Association in 1994 of their “Premio de las Americas”, as the writer “whose work best exemplifies the common humanity of the peoples of the Western Hemisphere” – a truly fitting tribute to this man of the people.

Sources:

- Delgado, Omar. 2015. “Ramón Rubín “El novelista etnólogo””. Laberinto, 13 June 2015.

- Gracia Noriega, Ignacio. 2009. “Ramón Rubín: un novelista rebelde”. Lne.es. 8 November 2009.

- Pérez-Peña, O. & Torres-González, G. (2001) “Ramón Rubín y la lucha por la salvación del lago de Chapala“. Renglones, revista del ITESO, núm.49. Tlaquepaque, Jalisco: ITESO.

- Ramón Bustos, Luis. 2001. “Donde la sombra de Ramón Rubín“. Jornada Semanal, 16 de septiembre del 2001.

- Rodríguez, Juan José. 2012. “Ramón Rubín: primeros cien años”. El Universal. 8 July 2012.

- Vargas, Rafael. 2012. “Centenario: La leyenda de Ramón Rubín” Proceso, 1 August 2012.

- Vogt, Wolfgang. 1989. “El Lago de Chapala en la literatura”. Estudios Sociales. (Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara), Año II, #5, 37-47.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).