Hilda Marie Osterhout was born in Brooklyn, New York in about 1925 and died in 2016. She grew up in a well-to-do family and, after attending Packer Collegiate Institute, was “presented to society” at the “Allied Flag Ball and Victory Cotillion in New York.” She then studied at Vassar College, where she won the Dodd Mead Intercollegiate Literary Fellowship for the best draft of a novel submitted by a college student in 1946, the year she graduated.

Her novel, provisionally titled Field of Old Blood (a Lorca quotation) was set in Mexico, and the award (an advance of $1500 against future royalties) enabled Osterhout to spend eighteen months in Mexico, divided between Mexico City and Ajijic, to complete the novel in 1946-47.

Her novel, provisionally titled Field of Old Blood (a Lorca quotation) was set in Mexico, and the award (an advance of $1500 against future royalties) enabled Osterhout to spend eighteen months in Mexico, divided between Mexico City and Ajijic, to complete the novel in 1946-47.

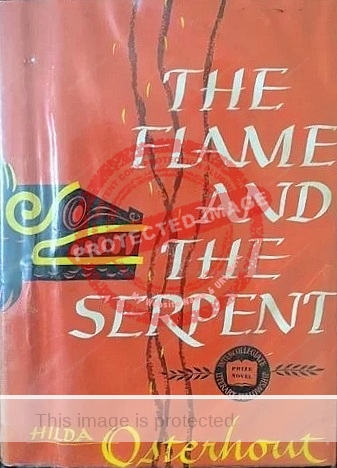

The book, finally titled The Flame and the Serpent, was published in 1948 by Dodd, Mead and Company, with a European edition published by Gollancz in London the following year.

Speaking to the Manor Club of Pelham shortly after her book was published, Osterhout recalled how she lived in Mexico City “under the strict chaperonage peculiar to the young girls of the country”, whereas, “In Ajijic I rented an adobe hut for $20 a month and paid two maids one dollar a week to look after me, and I learned the quiet feeling of danger that can surround you living in an Indian village where witch doctors still practice.” According to Osterhout, she had seen witchcraft “practiced on foreigners whom the Indians did not like, to the point where the foreigners left the village and never returned.” She also claimed that, “these Indian traditions are still carried on because they are taught in the Indian schools in connection with the ancient Aztec myths.”

Osterhout concluded that the main differences between the US and Mexico lay in the categories of history (where the US looked forward, and Mexico took inspiration from its history), art (where the art of Diego Rivera and others glorified the Indians), religion (a strong uniting factor in Mexico) and the position of women:

The women in Mexico are governed by tradition, yet they are utterly respected and adored becasue of the sole fact that they are women. Perhaps we have gained a lot when we gained our equal rights with men, but after seeing the way women are treated in Mexico I am beginning to think that we lost as well as gained.”

Osterhout is reported to have studied at the University of North Carolina and at UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), though details of her time spent at either institution are lacking.

Osterhout. Photo by Soichi Sunami.

The Flame and the Serpent had a mixed reception. According to Marc Brandel, writing in the New York Times, the book was “a remarkable rather than an admirable novel.” Despite its “faults of style and construction” “there shines through it, even at the its worst and most pretentious, one of those vivid talents that it is impossible to ignore.” The story is about a young girl’s first trip to Mexico, and her experiences of cultural differences she encounters, including those related to life, love and marriage. Brandel thought that the merits of the novel lay in “the sensitive beautifully written descriptions of certain facets of Mexican life as seen through the eyes of an American girl.”

Charles Poole, another reviewer in the same newspaper, described it as “One of the most unusual books about Mexico… since D. H. Lawrence grappled and groaned through that magnificent country’s mysteries.” He considered the writing to be “fresh and untarnished” though the author’s “interest in life still outruns her mastery of the novel’s form.”

Osterhout, who also wrote several book reviews for the New York Times. renewed the copyright of The Flame and the Serpent, her only novel, in 1976.

In 1950, Osterhout married Brinton Coxe Young, son of prominent impressionist artist Charles Morris Young. Hilda and her husband lost many of their family heirlooms in 1989 when burglars stole 19 paintings by Charles Morris Young and twenty works by other artists, as well as a small fortune in rare china, jewelry and many other items. The total haul, conservatively estimated at over $500,000, included a gold sealing ring that had belonged to Arthur Middleton, a maternal ancestor of Brinton Young and signatory of the US Declaration of Independence. This was not the first tragedy to befall the family. Charles Morris Young had lost almost 300 of his paintings in a house fire shortly before he died in 1964.

Several chapters of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village offer more details about the history of the literary and artistic community in Ajijic.

Sources

- Hilda Marie Osterhout. 1948. The Flame and the Serpent. Dodd, Mead and Company (and Gollancz, London, 1949).

- New York Times, 24 October 1948; 11 November 1948; 8 May 1949; 25 June 1950; 17 June 1951.

- The Standard-Star, 2 Feb 1949, 18.

- AP News. 1989. “Children of Pennsylvania Impressionist Lose Family Treasures,” AP News, 20 October 1989.

- Vassar Chronicle, Volume III, Number 34, 8 June 1946, 1.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).