Martin Dreyer (1909-2001) and his wife, Margaret “Maggie” Webb Dreyer (1911-1976), spent several weeks in Ajijic in 1962. The Dreyers, both established artists, had opened a joint gallery in Houston a few years earlier. Martin’s entertaining account of their stay in Ajijic is an interesting read.

Martin Dreyer was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1909, graduated from Northwestern University in Chicago, and died in Houston, Texas in 2001. His writing was first published in the 1930s, with short stories appearing in Esquire Magazine and several editions of Best Short Stories of the Year. He moved to Houston in 1940, and joined the staff of the Houston Chronicle in 1944. For about thirty years he combined reporting, feature writing and investigative journalism with travel articles.

In Houston, Martin met and married Margaret Lee Webb, who was born in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1911. From about 1960 to 1975, they ran Dreyer Galleries, their joint gallery in Houston, where they exhibited the works of many important Texas and Latin American artists, alongside related historical artifacts. The Dreyers were noted for their social activism, and their gallery raised the profile of many female and African American artists. (It also led to interactions with the Ku Klux Klan and a bullet hole in the front door, but that’s another story.)

Margaret studied at art at the University of Texas, Austin; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and at Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende.

The Dreyers’ son, Thorne Webb Dreyer, has ensured that this parents’ artistic achievements and legacy live on today. For more about Margaret’s life and work, see, for instance,”A tribute to Maggie, my mother” and his mother’s Wikipedia entry. Thorne’s summary of his father’s life and work is online as Martin Dreyer’s biography on AskART.

Martin exhibited in numerous group exhibits, including Houston Artists Exhibitions (1943-1945), Texas General Exhibitions (1943-1945), Dallas Museum of Fine Art (1949), Houston Museum of Fine Arts (1951), and the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston (in the 1950s). Margaret’s work also featured in numerous group shows, including Houston Artists Annual Exhibitions, Texas General Exhibitions, Texas Watercolor Society showings, and the Contemporary Arts Association (1957) and the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston. Her work won several major exhibition prizes, and she completed mosaic murals at Madding School, Houston (1966), Face of Cavallini Building, San Antonio (1966) and Face of Crawford Building, Houston (1967). Posthumous solo exhibits of her work were held at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston (1977) and at the University of St. Thomas (1979).

Our focus here is on Martin’s account of their stay in Ajijic.

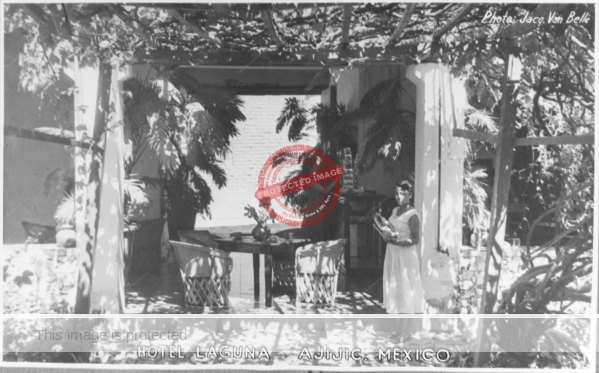

Jacques Van Belle. c. 1957. Hotel Laguna (later Hotel Anita), Ajijic.

Martin Dreyer’s account of their time in the “intrigue-charged Mexican village of Ajijic,” (“A Visit to Bohemia Below the Border”) is based on the recently opened inn where they stayed, an inn “built around a Spanish courtyard bursting with flowers and a flourishing papaya tree.” The inn’s landlady was “a bit dumpy, with a handsome face and black flashing eyes. A refined, matronly type.” A friend later explained that their hostess had previously been “One of the leading madams in Guadalajara.”

Dreyer paints a quick picture of the village, recognizing that initial impressions were not very encouraging:

Ajijic, an ancient Tarascan fishing village on the shores of Lake Chapala, is a colorful hangout for artists, writers and other American expatriates. Some of them drink it up and live it up to the tail end of their income. An occasional suicide marks the end of the road.”

. . .

On first sight of Ajijic you might not want a second sight. The narrow, cobblestoned streets are lined with dreary looking adobe houses. Indians squat around, cattle block your car and packs of mongrels yap and slink away. But if you hang around you’re in for a surprise. There’s a dream quality to this village beneath its green mountain range. And behind the adobe walls are flowerlush patios, colorful art studios and cosy apartments.”

Inevitably, the Dreyers were drawn to frequent the “Galleria” [La Galería], the gallery-bar near the plaza, where they joined the local Bohemian crowd in “an ancient building with floor-to-ceiling windows and modern paintings and sculpture adding eeriness to the candle-lit rooms.” One evening, while they were having a drink there, a flash flood swept down the street (calle Colón) from the mountains:

We sat in the flickering room, with sculptured faces peering at us from the shadows, and brooded over our assorted transgressions. The tequila drinks went a long way to easing the pain.”

Dreyer also tells the story of a “beautiful and shabby girl” living at the “deserted old mill in Ajijic used as a pad by a group of beatnik artists and writers.” She was in tears because she had just had a play accepted by a movie company. But tragedy followed. “Later, we heard, the deal was off. Later she shot herself.”

In addition to La Galería, Dreyer found that “A favorite hangout of the retirees was the home of a woman called Margot. High thick arches and tile floors on different levels, tasty arrangement of fine paintings and pre-Columbian sculpture, a hi-fi system’s swelling of superior music through the rooms.”

And, as Dreyer comments, Ajijic inspired art and creativity:

Painters find colorful subject matter everywhere. My wife went to the beach to sketch. Small boys – dark-eyed and fine-featured – gathered all sides and pushed close and all wanted to be in the picture. And all wanted to go to the States.”

After three weeks in Ajijic, as the Dreyers were packing the car for the long drive home, they gave the landlady a small bottle of perfume as a present. The landlady insisted they return inside the inn where she gifted them some hand embroidery. After Margaret responded with “some bath towels from the States,” the landlady immediately gave her an alpaca evening bag. The gift of one of Margaret’s small recent watercolors was matched by some dangling earrings. Then the ‘señor’ who helped run the inn appeared. It was Martin’s turn. In his immortal concluding words: “I gave him an old Army canteen. He presented me with a hand-carved wooden figure. We got in the car, said ‘Adios, amigos,’ and drove off before they could give us the inn.”

Somewhere in Ajijic is an original watercolor by Margaret Dreyer . . . .

Please get in touch if you know of any Margaret Dreyer or Martin Dreyer paintings related to Lake Chapala.

Aside: The inn the Dreyers stayed at was the Hotel Anita, which occupied a once extensive property (since subdivided into three) west of Ajijic plaza on the east side of Calle Juárez, between Hidalgo and Zaragoza. The hotel first opened in the mid-1950s as the Hotel Laguna, and was renamed Hotel Anita following its purchase in the early 1960s by Anita Chávez de Basulto (‘La Muñeca’). Noteworthy guests at Hotel Anita included prison muralist and artist Alfredo Santos. The Hotel Anita closed in about 1965. It reopened two years later as the Hotel Villa del Lago, which lasted only until about 1970.

Sources

- Martin Dreyer. 1962. “A Visit to Bohemia Below the Border.” Houston Chronicle, 8 April 1962, 11, 13.

- Janette Rodrigues. 2001. “Former travel editor Martin Dreyer dies.” Houston Chronicle, 13 March 2001.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).