Frieda Mathilda Hauswirth, also known after her second marriage as Frieda Mathilda Das, was an accomplished painter, writer, and illustrator, who is perhaps best remembered today for having painted one of the earliest portraits of Mahatma Gandhi.

Hauswirth visited Mexico from August 1944 to early in 1946. While it is unclear if this was her only visit, she definitely visited Ajijic on this trip: Neill James, in her account of Ajijic in 1945, described Hauswirth as “a naturalist from India”.

Actually, Frieda Mathilda Hauswirth was Swiss, but with very strong Indian connections. Hauswirth was born in Switzerland on 8 February 1886 and studied at the Universities of Bern and Zurich for two years before moving to California in about 1905 to attend Stanford University, from which she graduated with an A.B. in English in 1910.

Immediately after graduating she married a fellow Stanford student, Arthur Lee Munger, who later became a doctor. Their unconventional marriage ceremony on 7 August 1910 was held at the Temple Square in Palo Alto. The couple were “in street attire and unattended.” The ritual, “quite unlike that of any other church, in that it minimizes the religious and accentuates the philosophic and social side of marriage”, omitted any suggestion of “the inferiority and submission on the part of the bride”. Each “placed a ring on the fourth finger of the other in token of marriage, repeating the nuptial vows in unison”.

Hauswirth’s liberated approach to matters of the heart became apparent soon after marriage when she became infatuated with an Indian professor (and with India and its complex politics). A short-lived affair brought her marriage to an end and she and Munger divorced in 1916.

Frieda Mathilda Hauswirth. Illustration from Meine indische Ehe (1933)

While studying at Stanford, Hauswirth had become friends with a high-caste Indian student named Sarangadhar Das. Das had studied in Japan, funded by a wealthy patron in India, but turned his back on his patron (and his family) to continue his agricultural engineering studies at the University of California in Berkeley. After he graduated, he worked for several years in a sugar mill in Hawaii. Das and Hauswirth, who had now immersed herself in Indian literature and managed to get several articles published in the Modern Review of Calcutta, had always remained close friends. Hauswirth longed to visit and teach in India but wartime travel restrictions prevented her from realizing this plan. Das had proposed to Hauswirth several times over the years before she agreed to visit him in Hawaii, where they married in 1917.

The marriage made their migration status very complicated. Hauswirth lost her previously-acquired American citizenship even as Das was petitioning the court for his own naturalization. The legal situation was complex. The United States District Attorney opposed the petition “on the ground that the petitioner, being, a Hindu, is not eligible to ‘naturalization under Revised Statutes, section 2169, which limits naturalization to “free white persons” and those of African nativity and descent”, but local Hawaii Second Circuit Judge Edings eventually ruled that Das did indeed have the right to become a U.S. citizen.

Even the couple’s honeymoon was sensationally eventful: they were called as witnesses during the famous Hindu-German Conspiracy Trial in San Francisco where two men were killed in the courtroom.

Frieda and Das then lived in California for a short time, where Frieda took classes with Gottardo Piazzoni (1872–1945) at the California School of Fine Art (now San Francisco Art Institute) in San Francisco.

Artwork by Frieda Mathilda Hauswirth. Credit: askart.com

In 1920, following the death of Das’s father, the couple sailed for Calcutta, India, where Das tried to start a sugar factory in Orissa. The prejudices that were rife in the India of that time made life extremely difficult for Frieda. For instance, she was never able to meet her mother-in-law since if she had done so, the elder Mrs. Das would have “lost caste” and would have been reviled by friends and family alike. It also quickly became obvious to Frieda that her presence prevented potential investors from lending her husband the money needed to finance his sugar project. Not surprisingly, Frieda, a staunch feminist, found this situation intolerable and the couple agreed to live apart.

Sarangadhar Das went on to become a nationalist revolutionary who served in the Constituent Assembly of India that was responsible for framing the country’s independent constitution that took effect in 1950. He remained in politics until his death seven years later. A later account of his life and contribution to the Indian independence process, by Jatin Kumar Nayak, credits Hauswirth with having been instrumental in persuading Das that he should “return to India and make use of his expertise to improve the lot of his impoverished fellow Indians.”

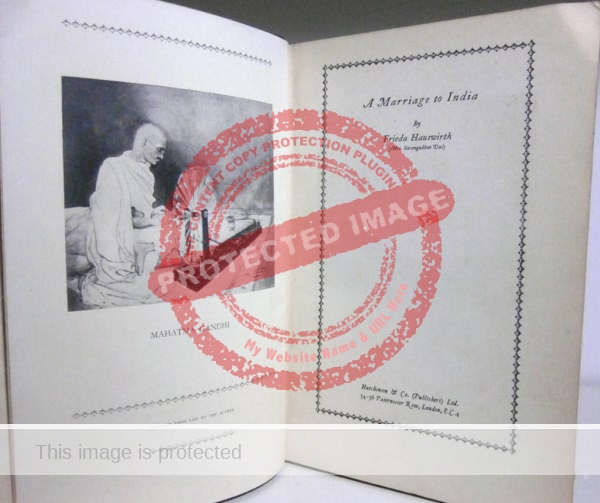

Frieda left India and returned to Switzerland to paint and write. She studied art in Paris and divided her time over the next decade between Europe and California, with occasional trips to India. Frieda’s book about her experiences in India, A Marriage to India, was published by Vanguard Press, New York, in 1930. It is a detailed, heartfelt account of her relationship with Das and the difficulties they encountered as an inter-racial couple in India in the 1920s. The book’s frontispiece is Hauswirth’s own 1927 sketch of Gandhi, who was a friend of her husband’s family.

In early 1938, she moved to California for six years. She sought to restore her American citizenship and announced that she was prepared to divorce Das if necessary in order to expedite the process.

In 1944, after building a cabin-studio at 11, El Portal Court in Berkeley, she decided to visit Mexico. The visit lasted from August 1944 to early 1946. As described by Hal Johnson, writing several years later about Hauswirth for the Berkeley Daily Gazette:

Then came the urge to paint in Mexico and to gather material there for a travel book. In August, 1944, she motored south of the border with “Lennie”, a cross between a German police dog and an Airedale, as her sole companion.

Mexican roads were like driving over washboard through which spikes stuck up. Tires were scarce in Mexico then as they were in the United States, but Frieda Hauswirth and her dog, “Lennie”, finally reached Ajijic Lake.

She made her headquarters in Chapala and did in oil some delightful paintings. Followed a sojourn in Mexico City and then a trip to Oaxaca, where she painted from the Zapotecs and Mixtecs, the most intelligent of Mexican Indians. She spent Christmas, 1945, in Monterrey, Mexico.”

There is an as-yet-unconfirmed report of an oil painting, labeled “Ajijic” on the back, by Hauswirth of a Mexican couple at a market which presumably dates back to this time.

Hauswirth flew back to Europe early in 1946 to live in Switzerland and study Italian. She revisited India in 1950, but eventually resettled in Berkeley, California, early in 1951. A contemporary newspaper account describes how she did not have wall space to hang “several of her earlier oil paintings which won prizes in Paris art shows. They are carefully packed away along with her more modern canvases painted in Mexico.”

Hauswirth became well known for the frescoes and portraits she painted. Her major art exhibits included shows at the Salon des Beaux Arts, Grand Salon, Paris (1926); in London; at the San Francisco Art Association (1920, 1925); in Boston; at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City (June 1931); and in Mysore, India.

Frieda Hauswirth wrote and illustrated several books including A Marriage to India (1930); Gandhi: a portrait from life (1931); Purdah, the Status of Indian Women (1932); Leap-Home and Gentlebrawn, A Tale of the Hanuman Monkeys (1932); Into the Sun (1933); Die Lotusbraut (1938); Allmutter Kaveri (1939).

This progressive woman, who had led and enjoyed an extraordinary life, died in Davis, California, in March 1974 at the age of 88.

Sources:

- Russell Holmes Fletcher. 1943. Who’s who in California, Vol. I (1942-1943).

- Frieda Hauswirth (Mrs Sarangadhar Das). 1930. A Marriage to India. New York: The Vanguard Press.

- Edan Milton Hughes. 1986. Artists in California, 1786-1940. Hughes Pub. Co.

- Neill James. 1945. “I live in Ajijic”, in Modern Mexico, October 1945.

- Hal Johnson. “So We’re Told”. Berkeley Daily Gazette, 29 October 1951, p 9

- Maui News. “Judge Edings Grants Citizenship to Das”. Maui News, 4 January 1918, p1.

- Jatin Kumar Nayak. 2011. “Orissa Whispers – Unsung Hero: Sarangadhar Das is one of the makers of modern Orissa”. The Telegraph, India, 7 March 2011.

- Oakland Tribune. “Berkeley Woman Balked, by Caste System of India”. Oakland Tribune (California), 30 March 30, p 13.

- The Plattsmouth Journal. “Murray Department: Former Plattsmouth Young Man married at Palo Alto, California“. The Plattsmouth Journal (Nebraska), 25 August 1910, p 6.

- The Stanford Daily. “Former Stanfordite To Divorce Hindu”. The Stanford Daily. Volume 93, Issue 26, 31 March 1938, p 1.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).