Is it right for someone who only ever produced a single artwork related to Lake Chapala to be included in this on-going series? My usual answer has been ‘No!’ but I make no apologies for this exception.

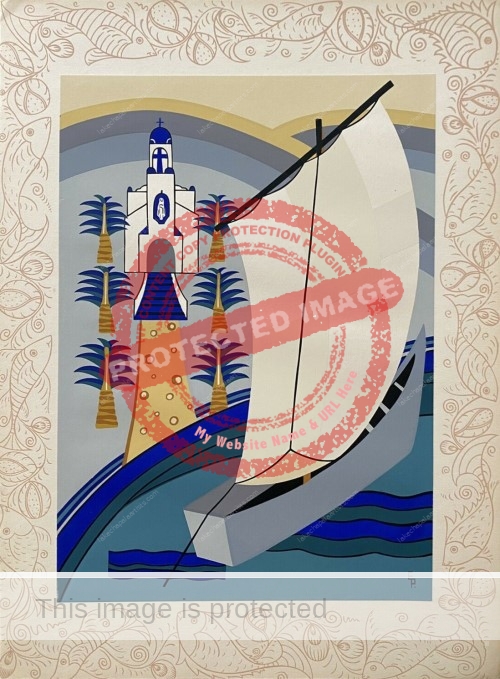

This superb silkscreen design of Chapala by Elma Pratt from the 1940s is so striking that it more than merits close attention.

Elma Pratt. Chapala. Silkscreen, published 1947. Border design by ‘Clemente’ of Tlaquepaque.

Cora Elma Pratt (she dropped the Cora in childhood) was born on 5 May 1888 in Chicago, Illinois, and died in Oxford, Ohio on 30 December 1977. Pratt grew up in an affluent family and accompanied her parents on trips to Europe. She graduated from Oberlin High School in Ohio in 1906, and then gained a bachelor’s degree in education from Oberlin College in 1912, majoring in music and social science. After a year in Europe with her mother, Pratt attended the New School of Design in Boston.

In 1918, as the first world war finally came to its end, Pratt—describing herself as an interior decorator—applied for a passport to travel to Great Britain and France to work with the American Red Cross. The diminutive Pratt (5’1″ tall with grey-green eyes) left the US shortly before Christmas and arrived in France on 6 January 1919. She worked initially with the YMCA in Paris, before applying for a new passport so that she could carry out “War relief work with the Christian Science Society of Italy.”

On her return from two years in Europe, Pratt completed a Master in Arts from Columbia University Teacher’s College (1922) and subsequently completed her formal education with a degree in art from the Vienna School of Art in Austria (1928).

In the course of her multiple trips to Europe, Pratt had encountered, and fallen in love with, Polish folk art. Determined to introduce it to other Americans, she organized the International School of Art. The first art program she ran was in Zakopane, Poland, in 1928. The International School of Art became the main focus of her working life, and she ran programs in Europe, Mexico and the US for more than thirty years.

Pratt was an avid promoter of Polish folk art in the US, working closely with the Brooklyn Museum, where she supplied artwork to their gift shop and organized folk art exhibitions, including the Polish Exhibition (1933-1934), the first ever exhibit of Polish folk art in the US.

Pratt returned to New York from a summer trip in Europe on 5 September 1939, only days before the second world war broke out. For the next few years travel to Europe was impossible, so Pratt turned her attention to folk art nearer home, including that of Mexico and Guatemala.

In the 1940s, Pratt began offering a summer school in Mexico, where her “students worked in Tlaquepaque, studying pottery designs under the shade of banana trees” and then continued on to take some classes in Taxco. The teachers hired by Pratt included Mexican printmaker Alfredo Zalce and Guatemalan-born painter Carlos Merida, and students were able to gain credit for the courses from the National University (UNAM).

While the precise dates and times of these programs in Mexico remain unclear, we can place Pratt in Guadalajara in 1944 and 1945. In February 1944, she gave a lecture to the Associación Cristiana Feminina in Guadalajara (Calle Tolsa #324) titled “Contribución de México al desorrollo artístico mundial” (Mexico’s contribution to world artistic development). By then her International School of Art was reported to have 14 locations in Europe and the Americas, including Mexico and Guatemala. The following summer, the Guadalajara daily El Informador devoted a column to Miss Mildred Pietschman, a member of the student group Pratt brought to Guadalajara. Pietschman, a music teacher, had previously taken art classes at the Universidad de Guadalajara and at the International School of Art in Rome, Italy. (Tragically, she died in an automobile accident while vacationing in Mexico in 1990.)

One significant by-product of Pratt’s numerous art school visits to Mexico (which included time in some quite remote areas) was her portfolio Mexico in Color. The portfolio, published in 1947 in an edition of 2000 copies, contained ten separate two-page folios with text and silkscreens: Lake Chapala of Jalisco, Shoppers in Ixtepec, Salt Boys of Chiapas, Traveling Salesman, Etla’s Market, Fisherfolk of Janitzio, Market in Uruapan, August 15th in Taxco, Tehuanas of Oaxaca, and From the Mountains of Oaxaca. The silkscreens, which are printed on silk and measure (including the decorative border) 44.5 x 30.5 cm (17.5″ by 12″), were designed by Pratt and printed by Adrian Duran in Mexico City.

When Pratt’s Mexican silkscreens were exhibited at the Misericordia University Pauly Friedman Art Gallery in Dallas in 2009, viewers were informed that the vibrant colors and bold designs chosen by the artist “place the viewers at the time and place of their creation… [and] allow the viewer to see what Pratt saw and experienced.”

The silkscreen of Chapala, dating from the 1940s, depicts La Capilla de Lourdes, with the steep, palm tree-lined street leading up to its entrance and a typical Chapala sail boat. Pratt explains in the accompanying text why she chose those elements for her design:

I have included in my “Mexico in Color” the picture of the little blue and white chapel just outside the town of Chapala, mainly because of my interest in the many people I see passing by. No matter how burdened with baskets, no matter how inconvenienced by the jog-jog of the donkey, off comes the sombrero as they pass the palm-bordered road running up to the chapel. Now that the little church is being enlarged, I wonder if the Indian who loves his diminutives will not share my regret at this change.”

The decorative design around the silkscreen “was painted by one of our Tlaquepaque boys, Clemente, with his dog-hair brush.”

Pratt emphasized the contrast between Chapala, “the playground of Jalisco” and Ajijic. In Chapala, many people:

make their living by merely adding to your pleasure: the mariachis whom you hire to play for you as you skim the surface of the beautiful lake in a launch or one of the more romantic rowboats, with their varied-colored awnings; the cheerful little men who rent you beach chairs, bright umbrellas or old tires; the ever-increasing group of men who make delicious home-made candies.”

On the other hand:

the tiny village of Ajijic… is no playground: days pass slowly or swiftly, as motivated by the daily routine of necessary tasks. There, as elsewhere in Mexico, the pat-pat of the tortilla symbolizes the narrow limits of the women’s lives; as does the constant net-mending symbolize the men’s devotion to the water. How they love to feel the tug of the big nets as their bronzed bodies bend with the pull of haul!”

Pratt refers to Witter Bynner “our own American poet… [who] has awakened in us still greater sensitiveness to the beauties of Lake Chapala” and to Neil James’ Dust on my Heart (1946), and Dane Chandos’ Village in the Sun (1945). In the context of Ajijic, Pratt explains that the village has been the scene for “not only good writing, but good painting.”

A decade later, Pratt produced a similar volume, Guatemala in Color (1958). She continued to be fascinated by folk art and, in her seventies, lived and taught in Egypt for four years.

Elma Pratt, educator, collector, artist, and philanthropist, never married and had no children. In 1970 she donated her extensive collection of international folk art, more than 2500 items in total, to the Miami University Art Museum in Oxford, Ohio. She moved to Oxford the following year and lived there the remainder of her life.

Note

- I offer a short history of La Capilla de Lourdes in chapter 27 of If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants (2020)

Sources

- Cardassilaris, Nicole Ruth. 2008. “Bringing cultures together: Elma Pratt, her International School of Art, and her collection of International Folk Art at the Miami University Art Museum.” Thesis for M.A. in Art History, University of Cincinnati.

- Taylor, Millicent. 1954. “On Tour With a Paintbrush: Elma Pratt and Her Art School,” Christian Science Monitor, 27 March 1954, 14.

- Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California) 7 July 1950.

- El Informador: 8 February 1944, 11; 10 February 1944, 7; 22 July 1945.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Absolutely adore this print and what the artist wrote about it!

Hi Lannie,

I happen to own that particular print, and others.

Let me know if you’d interested.

Carl Al

chucuri61@yahoo.com

646-409-8259