Poet and translator Clayton Eshleman repeatedly stressed in interviews the significance of a summer stay in Chapala in 1960 in determining his future direction and success. In addition to his own original works, Eshleman is especially well known for his translations of Peruvian poet César Vallejo and for his studies of Paleolithic cave paintings.

Ira Clayton Eshleman Jr. was born on 1 June 1935 in Indianapolis, Indiana. He discovered jazz in his teens and became a proficient jazz pianist and studied music for a short time in university, playing piano in bars to help finance his education. He graduated from the University of Indiana in 1958 with a degree in philosophy. Having by then discovered poetry, including the Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg, he immediately re-enrolled as a graduate student in English Literature.

Ira Clayton Eshleman Jr. was born on 1 June 1935 in Indianapolis, Indiana. He discovered jazz in his teens and became a proficient jazz pianist and studied music for a short time in university, playing piano in bars to help finance his education. He graduated from the University of Indiana in 1958 with a degree in philosophy. Having by then discovered poetry, including the Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg, he immediately re-enrolled as a graduate student in English Literature.

In 1959, he was introduced by an artist friend Bill Paden to Latin American poetry and was immediately drawn to the works of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904-1973) and Peruvian poet César Vallejo (1892-1938). Quickly realizing, aided by a bilingual dictionary, that existing translations of their poems had obvious flaws, Eshleman decided to do something about it, but knew that he first needed to improve his Spanish.

This was the impetus for him to hitchhike to Mexico City in the summer of 1959, “with a pocket Spanish-English dictionary and two hundred dollars”, and work on his Spanish, while meeting other poets along the way. The following summer, 1960, he spent several weeks in Chapala. In an interview many years later, Eshleman recalled that:

“The next summer I got a ride in the back of a flat-bed truck to Etzatlan, Mexico, ending up in Chapala for a couple of months. I rented a room in the home of an ex-American retired butcher named Jimmy George, who had a sixteen year-old Indian wife and lots of pigs and turkeys. I showed some Neruda poems to her one day and with her very modest English and my baby Spanish (and the faithful bilingual dictionary), we made some crude versions together, which were the real start of my Residence on Earth collection, published in Kyoto, Japan in 1962.”

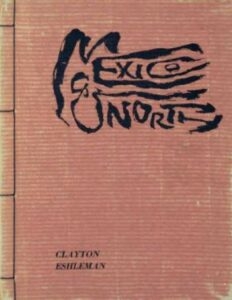

During his months in Chapala (and despite a bout of hepatitis), Eshleman also worked on many of the poems published in Mexico & North (privately published in Japan in 1962), the first collection of his own poetry.

Many of the poems in Mexico & North refer to Lake Chapala either directly or indirectly, including the very first one, “Evocation I”, which mentions Ajijic:

and its second part, Evocation II, which mentions Chapala:

In the same volume, “Water-Song” also mentions Chapala, with pithy descriptions of the lake and its water hyacinths, while “I Want to Live” is dedicated to “Humberto Anaya,” who at one time ran a real estate office in Chapala in association with Juan Manuel Valadez Alcantar.

Other Chapala-related poems in the volume include “Un Poco Tomado,” which has the line “lovely muddy Lago de Chapala“; “Dark Blood,” set in La Galería, Ajijic’s first art gallery-cantina; “The Spanish Lesson,” with its “A Sgt. in a Colinel’s cap” and mention of “The Chapala Society“; and “Prothalamion,” the final and longest poem in the book.

In a letter to Margaret Randall from about the time his book was published, Eshleman wrote that he “must have written 200 poems in a couple of months” during his first summer in Mexico, and that in his second summer he had joined Beat poets in Mexico City for poetry readings, and spent an evening (presumably in Jocotepec, Jalisco) with fellow poet/translator Lysander Kemp. (The Beat poets in the then-vibrant Beat scene in Mexico City in 1959 included surrealist poet Philip Lamantia and the multi-talented Anne McKeever, who hosted visiting jazz poet ruth weiss that year.)

Post-Chapala

In the summer of 1961, Eshleman married Barbara Novak. The couple then lived in Japan for three years, where Eshleman taught English and studied Eastern religions. Eshleman considered this period, when he was translating César Vallejo’s Poemas humanos, the beginning of his “apprenticeship to poetry”.

The Eshlemans then spent a year (1964-65) in Peru. Eshleman had gone there in the hope of persuading César Vallejo’s widow, Georgette, to allow him access to the poet’s original manuscripts, but she never did give her permission. While living in Lima, Eshleman worked on Quena, a bilingual literary magazine funded by the North American Peruvian Institute, but this magazine was suppressed for political reasons prior to publication. Though the young couple returned together to New York in 1966, they separated shortly afterwards.

Back in New York, Eshleman taught at the American Language Institute at New York University and began to publish a series of books under the Caterpillar Books imprint. He was an active participant in the anti-war movement and was jailed briefly as an organizer of the “Angry Arts” protest group.

On New Year’s Eve 1968 Eshleman met Caryl Reiter, who became his second wife. When he was appointed to the faculty of the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, the couple left New York for California. During a year in France (1973-1974), Eshleman taught courses in American poetry at the American College in Paris and the couple first visited the Paleolithic painted caves of the Dordogne region. This was the start of a prolonged interest in investigating the imagination and imagery of the Paleolithic painters. Eshleman’s major work on this topic was published in 2003 as Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination and the Construction of the Underworld.

For the latter part of the 1970s and early 1980s, the Eshlemans lived in Los Angeles, with the poet working for the Extension Program of the University of California at Los Angeles, the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, and a visiting lecturer at campuses in San Diego, Riverside, Los Angeles, and Santa Barbara. From 1986 to his retirement from academic life in 2003, Eshleman was Professor of English at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Clayton Eshleman died in January 2021.

During his prolific career, Eshleman had work published in more than 500 magazines and newspapers, and also founded and edited two important literary magazines: Caterpillar (1967-1973) and Sulfur (1981-2000).

Eshleman’s books of poetry and prose include Mexico and North (Tokyo, Japan, 1961); Walks (New York: Caterpillar, 1967); The House of Okumura (Toronto: Weed/Flower, 1969); Indiana (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1969); The House of Ibuki (Freemont, MI: Sumac Press, 1969); Altars (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1971); Coils (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1973); Realignment (Kingston, NY: Treacle Press, 1974); The Gull Wall (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1975); On Mules Sent from Chavin: A Journal and Poems (Swanea, UK: Galloping Dog Press, 1977); What She Means (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1978); Fracture (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1983); The Name Encanyoned River: Selected Poems 1960-1985 (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1986); Under World Arrest (Santa Rosa: Black Sparrow Press, 1994); Erratics (Rosendale, NY: Hunger Press, 2000); Everwhat (Canary Islands: Zasterle Press, 2003); An Alchemist with One Eye on Fire (Boston: Black Widow Press, 2006); The Grindstone of Rapport: A Clayton Eshleman Reader (Boston: Black Widow Press, 2008); and Anticline (Boston: Black Widow Press, 2010).

Eshleman won numerous literary awards, including a National Book Award for Translation, the Landon Translation prize from the Academy of American Poets (twice), a Guggenheim Fellowship in Poetry, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a Rockefeller Study Center residency in Bellagio, Italy.

And to think that it all began at a butcher’s home in Chapala . . .

Lake Chapala Artists & Authors is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission. Learn more.

Note: This is an updated version of a post first published in 2016.

Source of quotes:

- “An expanded version of ‘Niall McDevitt Interviews Clayton Eshleman.'” – The Wolf.

- “An Interview with Clayton Eshleman; Going to the Moon with Some Wonderful Ghosts:Literary Translation and a Poet’s Formation” by Ethriam Cash Brammer.

- Harris Feinsod. 2017. The Poetry of the Americas: From Good Neighbors to Countercultures. Oxford University Press

Comments, corrections or additional material welcome, whether via email or comments feature.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).