Ireneo Paz, the paternal grandfather of Nobel Prize-winning author Octavio Paz, was a respected writer, journalist and intellectual.

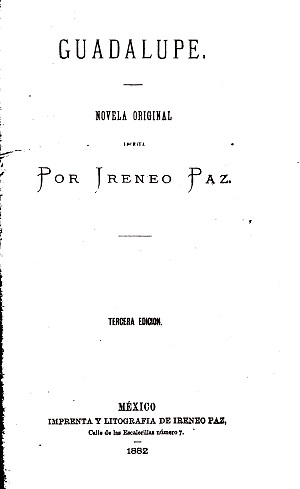

One of his novels, Guadalupe, first published in 1874, is an illustrated romance novel (in Spanish) with several descriptive passages relating to Lake Chapala. The story is set in an unnamed lakeshore village. The text includes several mentions of specific towns and villages around the lake, and one of the middle chapters is devoted to the events that arise from a storm on the lake.

While the style of the writing is “dated”, the story is clearly told. English speakers with an intermediate level of Spanish should find the plot and dialogue relatively easy to follow. The third edition of this book can be downloaded for free (as a pdf file or for ereaders) via Google Books:

- Ireneo Paz. Guadalupe (1882). Google Books.

Ireneo Paz Flores was born 3 July 1836, in Guadalajara, and died in Mexico City on 4 November 1924. A lawyer by background, he founded several literary magazines and was editor of the national magazine La Patria Ilustrada, which, in 1889, was the first major publication to regularly accept the often-startling cartoons and skeleton-like calaveras drawn by famed graphic designer and engraver José Guadalupe Posada.

Ireneo Paz Flores was born 3 July 1836, in Guadalajara, and died in Mexico City on 4 November 1924. A lawyer by background, he founded several literary magazines and was editor of the national magazine La Patria Ilustrada, which, in 1889, was the first major publication to regularly accept the often-startling cartoons and skeleton-like calaveras drawn by famed graphic designer and engraver José Guadalupe Posada.

In a prolific career, Ireneo Paz wrote more than 30 books, including poetry, plays comedy, memoirs and novels. His best-known works are a study of Malinche and a book about the famous Mexican (Californian) bandit Joaquin Murrieta. Among his works are: La piedra del sacrificio (1871); La manzana de la discordia (1871); Amor y suplicio (1873); Guadalupe (1874); Amor de viejo (1874); Doña Marina (1883); Leyendas históricas de la Independencia (1894); Vida y aventuras de Joaquín Murrieta, famoso bandolero mexicano (1908); Porfirio Díaz (1911); Leyendas históricas (1914).

Tragically, the political differences between La Patria (edited by Ireneo Paz) and La Libertad (edited by Santiago Sierra Méndez) led to a duel between the two men in April 1880, in which the latter was killed.

During the Mexican revolution, Mexico City was the scene of fighting between rival groups. In 1914 (the year his grandson was born), Ireneo Paz’s spacious, well-appointed house and printing shop in the heart of the old city were ransacked and Paz moved the family out of the then-city to live in Mixcoac.

Ireneo Paz’s own life and writing career are interesting, but his greatest contribution to Mexican literature is through the influence he exerted on his grandson, Octavio, who lived under the same roof throughout his childhood.

Ireneo Paz’s own life and writing career are interesting, but his greatest contribution to Mexican literature is through the influence he exerted on his grandson, Octavio, who lived under the same roof throughout his childhood.

As British translator, journalist and non-fiction author Nick Caistor explains in his biography of Octavio Paz, Ireneo Paz was his grandson’s “direct link to the struggles for Mexican independence in the nineteenth century, in which he had personally played as significant role, and to Mexican history in general.”

However, despite supporting the liberal movement led by Benito Juárez in the 1850s, and fighting against the French, most notably in the city of Colima, Ireneo Paz had eventually become a staunch supporter of the modernization efforts of Mexico’s multi-term dictator President Porfirio Díaz.

Caistor justifiably argues that Ireneo Paz exerted an influence over his grandson that extended well beyond politics:

As a novelist he was one of the precursors of the ‘indigenista’ movement, which sought to make the indigenous inhabitants of Mexico protagonists of the national narrative for the first time. The awareness of the presence of the ‘other’, the silenced, marginalized voice of the country’s first inhabitants, fascinated Octavio from an early age.

At the same time, the Paz household was open to outside influences. Despite his opposition to the French invasion, by the 1880s Ireneo Paz saw France as the emblem for modernity. In 1889 he even travelled to Paris as an exhibitor at the Exposition Universelle where he displayed examples of his printing and binding.”

Not surprisingly, the Paz household was full of books, including not only those written or printed by Ireneo but also a fine collection of Spanish and French literature, many of the volumes brought back from Paris. Growing up in such an atmosphere undoubtedly wove its spell over young Octavio who became one of Mexico’s most famous and revered poets.

Paz’s exploration of the Mexican identity, El laberinto de la soledad, first published in 1950, was elegantly translated by Lysander Kemp, and published in 1961 as The Labyrinth of Solitude: Life and Thought in Mexico. Kemp, who later became chief editor of the University of Texas Press, had his own connections to Lake Chapala: he was a long-time resident (1953-1965) of Jocotepec, at the western end of the lake.

Sources:

- Anon. “Efemérides del Periodismo Mexicano: Irineo Paz Flores”. Jul 3, 2016

- Nicholas Caistor. 2008. Octavio Paz. Reaktion Books. 208 pages]

- Braulio Peralta, 2014. “La Letra Desobediente. Ireneo Paz“. Milenio, 14 March 2017.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).