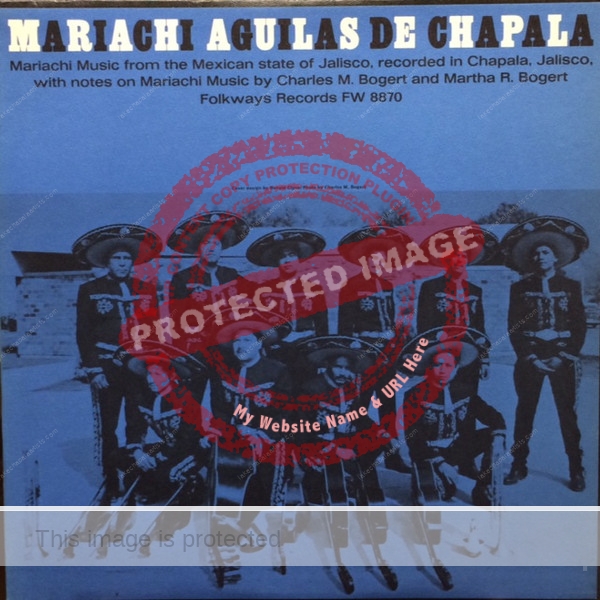

Charles Bogert (1908-1992) and his wife Martha (ca 1917-2010?) visited Chapala in 1960 and recorded a mariachi band – the “Mariachi Aguilas de Chapala” – playing several well-known songs. The recordings were released on a Folkways record later that year, and accompanied by explanatory notes written by the couple.

One of the curiosities about this record is that it came about almost by accident. Bogert had not visited Chapala to record mariachi music but was there with funds from the American Museum of Natural History to record and analyze the mating calls of the local frogs!

Charles Mitchill Bogert was born 4 June 1908 in Mesa, Colorado. He gained his undergraduate (1934) and master’s degree (1936) at University of California, Los Angeles before being appointed as assistant curator in the Department of Herpetology (Snakes) at the American Museum of Natural History from 1936-1940. He was promoted to associate curator in 1941 and became curator in 1943, a position he held until 1968.

His work with snakes included several field expeditions to Mexico, the earliest in 1938. He also traveled extensively in Central America, researching snakes and frogs in Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

Bogert published numerous articles in academic journals related to his chosen field of expertise and was made the first president of the Herpetologists’ League in 1946. From 1952 to 1954 he served as president of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, and in 1956 was vice-president of the Society for the Study of Evolution.

Just how did the mariachi recordings come about?

In 1957, Folkways Records had released an LP of recordings made by Bogert (many of them in the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona) entitled Sounds of North American Frogs. The following year, Folkways issued an other LP – Tarascan And Other Music Of Mexico (FX 8867) – which featured tunes from Chihuahua, Jala, Tepic and Lake Pátzcuaro and included a 12-page booklet by the Bogerts. In 1959, Folkways released Sounds of the American Southwest (FX 6122).

In 1960, the American Museum of Natural History awarded Bogert funds and provided him with the equipment to visit Chapala and record the sounds of that area’s local frogs. It was in the course of this trip that the Bogerts recorded the Mariachi Aguilas de Chapala.

In their notes, the Bogerts recognized that though “The mariachi band may be no more typical of Mexico than the sahuaro cactus is typical of the American deserts… [it] is now as prominent in Mexican culture as the giant cactus is in the desert landscapes of Arizona and Sonora.” They offered some historical context to the development of mariachi music, though modern scholars of the origin of mariachi music would beg to differ with their version.

The Bogerts noted that there was an on-going decline in the amount of live music in Mexican villages:

“Not so many years ago almost every village in Mexico supported a brass band or a small orchestra, sometimes both. Today much instrumental groups are largely confined to cities and the more prosperous towns. In many villages the bandstand in the center of the plaza has the neglected air of an unused edifice, which leads one to suspect that the sole source of music is now the ubiquitous loud-speaker. Before the advent of these unfortunate but less expensive substitutes for the local musician, each region had its own folk-music rather than the homogenized product of the radio station.”

According to the Bogerts,

“Another contributor to the decline of Mexican folk-music is the tourist, especially the American. Too often he limits the musicians’ repertoire by insisting on hearing only the pieces he already knows or has heard in the United States…. If this trend continues, songs purely local in character may fade from the scene.”

Their recordings of the Mariachi Aguilas de Chapala were made not in a studio but in the open air, “on the third-story roof garden of the Country Club Arms, an ultra-modern apartment hotel in Chapala” owned by Mrs. James Grant and her late husband. [Aside: If anyone can tell me more about the Country Club Arms, please get in touch!]

The band had ten musicians, playing two trumpets, three violins, one guitarrón, one guitarra de golpe, and three guitarras. The songs recorded were Atotonilco; Las Olas; La Negra; Jarabe Tapatío; La Bamba; Chapala; Tecalitlán; La Adelita; Las Bicicletas; Ojos Tapatíos; Ay, Jalisco, No Te Rajes!; Las Mañanitas; and El Carretero Se Va.

Despite their reservations about the possible role of tourists in the decline of the village mariachi, the Bogerts clearly recognized the importance of tourists as a source of income for mariachi musicians:

“Needless to say, tourists are a good source of income for these peripatetic bands. When business is slow, one member of the orchestra, usually carrying only a violin, sometimes approaches an unwary tourist and asks if he would like some music. lf the answer is yes, the tourist may find that instead of having hired one man to playa softly romantic violin, he is suddenly surrounded by ten musicians who burst forth with their loud music, sometimes in cheerful, cacophonic competition with a blaring radio. The tourist’s discomfiture rarely lasts, however, for he and his party are soon infected by the lilting melodies and foot-tapping rhythms of the mariachi. Whatever fee he pays will be small in comparison with the pleasure he derives from the memories he takes with him.”

During the 1960s, the Bogerts continued to visit Mexico, with Charles Bogert, in his role of herpetological researcher, focusing mainly on the Oaxaca area.

Bogert has the distinction of having had at least 21 reptiles and amphibians named after him by his colleagues, including a subspecies of the venomous Mexican beaked lizard called Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti.

Bogert died at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on 10 April 1992.

Bogert’s recordings and notes about mariachis are valuable reminders of Chapala’s long musical history, but the Bogerts were by no means the first visitors to Chapala to laud the irresistible attractions of mariachi music. For example, in 1941, David Holbrook Kennedy became fascinated by a local mariachi band, especially by one of its singers in particular.

Nor was mariachi music the only attraction for anthropologists interested in music. At the start of the 1950s, a well-known American musicologist – Sam Eskin – visited Ajijic for a short time and (from the patio of the Scorpion Club) recorded the ambient sounds of a religious festival in Ajijic, complete with church bells and pre-dawn firecrackers.

Sources:

- Charles Bogert and Martha Bogert. 1960. “Mariachi Aguilas de Chapala”, a collection of mariachi music from the Mexican state of Jalisco. (Folkways FW 8870, 12″ 33rpm LP.)

- Barbara Krader. 1961. Review of Folkways record “Mariachi Aguilas de Chapala”. Ethnomusicology (University of Illinois), Vol 5 #3, September 1961, p 227.

- Charles H. Smith. 2005. “Bogert, Charles Mitchill (United States 1908-1992)” (web)

- Charles W. Myers and Richard G. Zweifel. 1993. “Biographical Sketch and Bibliography of Charles Mitchill Bogert, 1908-1992”, in Herpetologica, Vol. 49, No. 1 (March 1993), 133-146.

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.