Arriving in Chapala in 1895, Italian count Guiseppe Antona and his friends dismounted at the ‘Inn of the Nueva Purissima’ (sic) which was “more suited to be called a stable than anything else,” since the rooms had no windows. Antona had arrived at a building (long since demolished) known as Mesón de la Purísima, believed to have been located where Avenida Francisco I Madero #232 is today. By a curious twist of fate, the replacement building, dating from the early 1930s, has once again become a hostelry, though one offering a far superior level of accommodation.

Sketch of Chapala, perhaps by Antona, published in The Detroit Free Press, 1895.

In about 1904, Meson de la Purisima, valued at $1000 pesos, was described as being about 1400 square meters in area, with a covered passageway, a patio, eight stables and nine terraced areas. It is unclear who owned it at that time. However, by 1930 the property was owned by Juan José Barragán, the widower of María de los Angeles Morfín de Barragán (1867-1926).

Following Juan José Barragán’s death in Chicago in April 1930, the property was one of several inherited by their six children. In April 1932, five of the six—engineers Juan José and Luis, lawyer Daniel, and their two sisters, Luz and Paz—sold Mesón de la Purísima to their brother, Alfonso, for $1000 pesos. Mesón de la Purísima (then Calle del Muelle #25) was listed at that time as a roughly rectangular property extending about 50 meters west from its 22.7 meters of street frontage to the east.

Three years later, Alfonso Barragán sold the property to Carlota Bohnstedt de Monteverde for $8000 pesos. The increase in value is noteworthy, but the new deed in October 1935 made it clear that the original building had been torn down and replaced by a new house with the (then) address of Madero #30.

This scenario raises two especially interesting questions. First, who designed and built the new house? And, secondly, who was Carlota Bohnstedt de Monteverde?

A forgotten work by Luis Barragán?

It seems highly likely that Alfonso would have entrusted the building of his new house to one or both of his engineer brothers. Oldest brother Juan José (1897-1975) had designed and built homes in Guadalajara, and had been closely involved in numerous other major projects, including the construction of the La Capilla-Chapala railroad, completed in 1920. Luis (1902-1988), a couple of years younger than Alfonso, had returned from Europe to dedicate himself to developing his skills as an architect. Recognized today as the most influential Mexican architect of the twentieth century, Luis had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1976, and is the only Mexican ever to have won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. The two brothers had worked together briefly in Guadalajara before Luis established his own architectural practice.

Following his father’s death in 1930, Luis had spent 1931-32 transforming the family home (Avenida Madero #411) in Chapala into a modernist residence, ably assisted in the process by his talented colleague Juan Palomar y Arias. The revitalized residence was bought by American poet Witter Bynner in 1940. By 1934, Luis had also drawn up some ideas (never executed) for Villa Niza in Chapala (Avenida Hidalgo 250) for the Newton family, and had completed a significant remodeling for Gustavo Cristo’s lakefront vacation home at Paseo Ramón Corona #10.

But what was Luis doing between 1932 and 1934? This gap in his timeline coincides neatly with when brother Alfonso was replacing Mesón de la Purísima, so it seems highly probable that Luis was involved in that major project, too. If this can ever be proven to be the case, it would add one more building to the list of homes designed, transformed or remodeled by this illustrious Mexican architect.

Charlotte (Carlota) Bohnstedt de Monteverde

The story of Charlotte Bohnstedt de Monteverde (birth name Gertrud Adelheid Eva Gottliebe Charlotte Bohnstedt) is equally intriguing. Born in Berlin, Germany, in 1889 to Gertrud Hientzsch and Max Bohnstedt, Charlotte was only an infant when Max abandoned the family and moved to New York, where he initially worked as a clerk. Shortly after Max was granted US citizenship, he and Gertrud divorced.

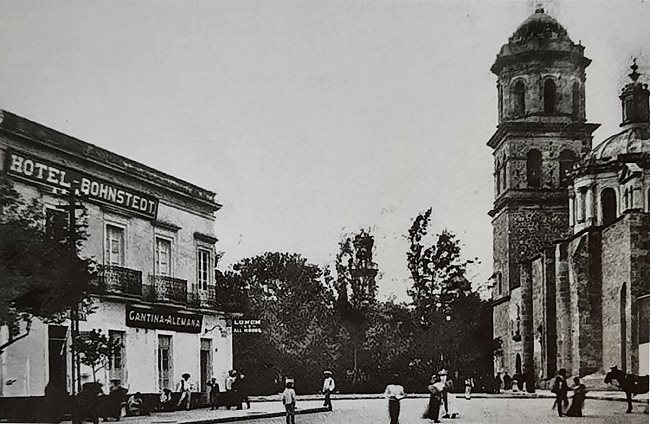

In about 1904, Max moved to Mexico and settled in Guadalajara. Known in Mexico as Máximo, he worked for a time as manager of the popular Hotel Cosmopolita, overlooking Plaza San Francisco and the then terminus of the Mexican Central Railway. (The hotel was owned by German businessman Francisco Fredenhagen, who has numerous interesting links to Chapala.)

In 1906, The Mexican Herald announced that Máximo Bohnstedt had been appointed manager of the Lake Chapala Navigation company, following the death of former manager Julio Lewells.

Somehow, Máximo was able to buy the La Alemana cantina, which occupied the ground floor of the Hotel Alemán, which adjoined the Cosmopolita. He immediately advertised for a first class cook willing to invest $300 to $500 to run a restaurant alongside his ‘established’ bar. This legendary cantina, with its outstanding German food, flourished for decades, before finally closing a few years ago.

Hotel Bohnstedt and Cantina Alemana. Photographer and date unknown.

In about 1909, Máximo acquired the entire building, and renamed it Hotel Bohnstedt. Between the bar, hotel, and a related sideline in trading Mexican curios and relics, Máximo apparently amassed a small fortune.

Máximo never remarried and, when he died in April 1923, left all his real estate and personal property to Charlotte, his only child. Three months later, 34-year-old Charlotte, accompanied by her mother, left Germany and moved to Guadalajara to administer his assets.

In 1929, Charlotte (known in Mexico as Carlota) married Alfonso Monteverde, a Sonora-born resident of Los Angeles. The couple lived with Gertrud in Guadalajara, and Alfonso administered the La Alemana cantina. Carlota registered her marriage and assets formally in Mexico, and made it abundantly apparent that she and Alfonso had agreed to bienes separados (separate property). The document listing Carlota’s real estate portfolio in Guadalajara is the longest list of its kind I have ever seen.

El Informador, the Guadalajara daily, reported that Carlota and Alfonso spent the summer of 1942 in Chapala, which coincides nicely with when she purchased the Alfonso Barragán house. At that time, Carlota also owned other property in Chapala, including an undeveloped lot on the eastern side of Francisco I. Madero.

Later occupants of Madero 232

It is not yet clear when Carlota Bohnstedt sold the property. But, by 1951, the ‘Salazar’ house (as it was then called) was rented by the musical and artistic Campbell family, who had retired to Chapala. The Campbell family—comprised of four siblings: Hilary, Elsa, Amy and their brother, Alan—lived here for five years while Amy and Alan designed and built a brand new home at Calle Niza #10, near the chapel of Nuestra Señora de Lourdes. In 1957, a year after they moved in, Life magazine’s Leonard McCombe photographed them at their new home for a photo essay documenting the American community at Lake Chapala. In 1976, Hilary Campbell, the last surviving family member, donated—in memory of her sister Elsa who had died a decade earlier—the family Baldwin grand piano to the Lake Chapala Auditorium for its grand opening.

Avenida Madero #232, August 2013. Credit: Google Street View.

Though there are currently substantial gaps in the timeline of this building, it was later used for many years as the Chapala branch of the Guadalajara-based investment firm Allen W. Lloyd (which later merged with Actinver). In 2019, following some remodeling, the property became Plaza Chapala Hotel, a beautifully appointed boutique hotel.

From rustic inn of dubious merits in the 1890s to a luxury boutique hotel in the 2020s! Who would have thought it?

The stories of dozens of other historic buildings in Chapala are told in If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s Historic Buildings and Their Former Occupants (also in Spanish as Si las paredes hablaran: Edificios históricos de Chapala y sus antiguos ocupantes). Lake Chapala: A Postcard History uses reproductions of more than 150 vintage postcards to explain why and how Lake Chapala became such an important international tourist destination.

Acknowledgment

Kudos to Rogelio Ochoa Corona, whose long-running series of short video cápsulas about Chapala deserves the widest possible audience, for bringing the early land ownership details of this property to my attention.

Sources

- Guiseppe [Giuseppe] Antona. 1895. “Shooting Teal Duck at Lake Chapala.” The Detroit Free Press, 3 March 1895, 11.

- Leonard McCombe (photographer). 1957. “Yanks Who Don’t Go Home. Expatriates Settle Down to Live and Loaf in Mexico.” Life, 23 December 1957.

- Luciano Sandoval. 2023. Esta vida es un sufrir. La cantinas de Guadalajara (1898-2023). Zapopan: Editorial Innovación Educativa, SA de CV.

- Thomas Allen Bohnstedt. Undated. “The Brodtkowitz Bohnstedt Line: Max Bohnstedt, and Hotel Bohnstedt in Mexico.”

- The Mexican Herald: 6 June 1906, 3; 7 Nov 1908, 8.

- El Informador: 18 June 1942, 10; 26 June 1942, 2; 8 July 1942, 9.

Comments, corrections and additional material welcome, whether via comments feature or email.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

I love reading about Luis Barragan. I will be touring his home in CDMX in the coming days and will share this piece with Arq. Guillermo Eguiarte who directs the Casa Barragan. I work with Equiarte in the 1990’s when he worked for the CPTM in Canada and Japan.

Saludos

Greg; Thanks for your comment. I’ll let you know if/when I find out more about this particular property. Cheers, Tony.

Excelente artículo Tony. Justo el 3 de julio de 1934 Juan José y Luis presentaban para el concurso del Gran Parque de la Revolución su propuesta a la que denominaron “Evolución” y para el día 8 se comunicaba que los Barragán habían ganado la convocatoria sobre los ingenieros Martínez Negrete y Castellanos, Rafael Urzúa y Aurelio Aceves Mucho que investigar respecto a los Barragán en Chapala. Saludos!

Gracias, tocayo. ¡Espero que tu y/o tus estudiantes siguen investigando el legado de Barragán! Saludos!