Everyone knows that Lake Chapala has attracted hosts of famous writers over the years – after all, without them, this blog would have been a bit pointless! However, as I suggested in “Did Somerset Maugham ever visit Lake Chapala?” some famous writers have been associated with the lake despite never visiting it. Is this also the case for the Nobel Prize-winning author Ernest Hemingway? Did he ever actually visit or work at Lake Chapala?

Señor Google turns up several articles and websites claiming Hemingway-Lake Chapala links. One in particular, entitled “Neill James—Ajijic’s Woman of the Century!” and first published in the 19 February 2012 edition of the USA Today’s weekend feature, La Voz de Mexico, makes some strong claims about Ajijic and Hemingway.

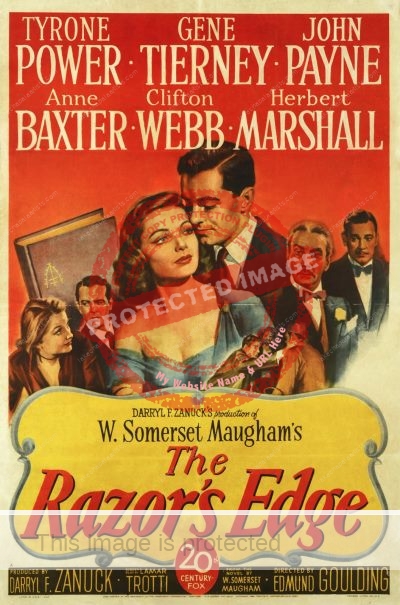

Ernest Hemingway and his trusty Underwood typewriter [See Sources for image credit]

To quote the article:

“Her publisher was Scribner’s, who at the time was also publishing Thomas Wolfe, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway—three of the most legendary writers of the 20th century.

Neill’s five books introduced and drew flocks of writers to Lakeside to share in her wealth of information. As the desire to travel began to subside and she settled in Ajijic, Ernest Hemingway, D.H. Lawrence, George Bernard Shaw, plus the editor of Life Magazine, came to visit her.”

The first sentence is fine: Neill James was indeed published by Scribner’s as were the other authors named, and it is perfectly conceivable (though by no means proven) that she met one or more of the other authors when visiting Maxwell Perkins at his offices in New York. It is even possible, as Laura Bateman wrote in Ajijic: 500 Years of Adventures, that, “Once, while waiting in Perkins’ outer office, Neill witnessed the notorious fist fight between Ernest Hemingway and Max Eastman.” That event occurred in August 1937.

The second sentence has some elements of truth about it, but the third – about Ernest Hemingway, D.H. Lawrence, George Bernard Shaw, and the editor of Life magazine visiting James – is wishful thinking and completely unsupported by the available evidence.

D. H. Lawrence was long dead before Neill James ever arrived in Ajijic, so that claim is clearly bunkum. (Lawrence, who died on 2 March 1930, lived in Chapala from May to July 1923.)

There is no evidence that George Bernard Shaw ever visited Lake Chapala, though it is remotely possible that the great English philosopher met Miss James somewhere else. Note that, by the time James settled in Ajijic, Shaw was already 88 years old. I do have lots of sympathy for the idea that Shaw can be linked to Mexico since he apparently once said that, “The two most beautiful things in the world are the Taj Mahal and Dolores del Rio”! (Dolores del Río was a stunningly beautiful Mexican actress from Mexico’s golden age of cinema).

I have never found any evidence that any serving editor of Life magazine visited Chapala to call on James or anyone else, though three photographs of Neill James in Ajijic do appear in Leonard McCombe’s photo essay for Life magazine, published in 1957.

The Hemingway-Chapala claim, which has since been repeated in International Living, seems equally inaccurate. Hemingway’s life has been painstakingly analyzed by a small army of biographers, but Lake Chapala never makes an appearance.

So far as I am aware, the only significant time Hemingway ventured into Mexico was a visit to Mexico City (from Cuba) in March 1942, which later came to the attention of the FBI because he apparently checked into the Reforma Hotel under an assumed name and met Gustav Regler, a friend from his time in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. (Regler himself did visit Ajijic several years later.)

While I’d love to be proved wrong, the idea that Hemingway ever visited or lived at Lake Chapala is just one more literary myth.

Sources

- Laura Bateman. 2011. “Neill James”, a chapter in Alexandra Bateman and Nancy Bollenbach (compilers). 2011. Ajijic: 500 years of adventurers (Thomas Paine Chapter NSDAR).

- Mary Dearborn. 2017. Ernest Hemingway – A Biography. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Tod Jonson. 2012. “Neill James—Ajijic’s Woman of the Century!” in USA Today’s weekend feature La Voz de Mexico, 19 February 2012 edition; reprinted in El Ojo del Lago, September 2012.

- Leonard McCombe. 1957. “Yanks Who Don’t Go Home. Expatriates Settle Down to Live and Loaf in Mexico.” Life, 23 December 1957.

- David Ramón. 1997. Dolores del Río. Editorial Clío.

- Matt Reimann. 2015. “When Ernest Hemingway Fought Max Eastman“, at bookstellyouwhy.com, 8 June 2015.

- Nicholas Reynolds. 2012. “A Spy Who Made His Own Way. Ernest Hemingway, Wartime Spy”, in Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 56, No. 2 (Extracts, June 2012).

- Image credit: https://player.watch.aetnd.com/player.html?tpid=572995835 [13 Sep 2018]

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.