The famous American writer, composer and translator Paul Bowles (1910-1999) was a frequent visitor to Mexico in the late 1930s and early 1940s prior to moving to live in Morocco in 1947. Bowles spent a few relaxing weeks in Ajijic, on Lake Chapala, in the first half of 1942.

Paul Bowles was born in New York on 30 December 1910 and displayed early talent for music and writing. After attending the University of Virginia, Bowles made several trips to Paris in the 1930s, and also visited French North Africa in 1931. During the late 1930s and most of the 1940s, Bowles was based in New York where he composed music (primarily for stage productions) while making frequent trips south to explore the sights and sounds of Mexico and elsewhere, trips which had a profound influence on his musical compositions.

Bowles’ interest in visiting Lake Chapala dates back to 1934, when he was considering accompanying Bruce Morrissette in traveling around Mexico. In March 1934, Bowles wrote to Morrissette that, “A while ago I made a list of what seemed to be the best places there: Campeche, Necaxa, Toluca, the baja part of Baja California, Mazatlán, Pátzcuaro, perhaps Lago Chapala, Morelia, which looks to be lovely, Tepatzlán, Cholula, Amecameca and Xochimilco …”

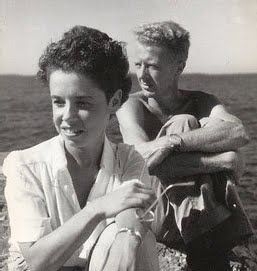

In 1937, Bowles met Jane Auer at a party. When they met again, accidentally, a few days later, Jane suggested to Bowles that he “take her to Mexico with him.” Auer and Bowles married 21 February 1938, and had a successful, if unconventional, marriage that lasted until her death in 1973.

[Jane Sydney Auer (1917-1973) was an American writer and playwright. Her novel, Two Serious Ladies, first published in 1943, may have been the catalyst that resulted in Bowles’ own novel-writing career. Jane Bowles suffered a stroke in 1957, from which she never fully recovered. She died in 1973 at a clinic in Spain.]

They took a Greyhound bus to reach Mexico on their first trip together in 1937, with Bowles hiding 15,000 anti-Trotsky stickers in his luggage. In Mexico, he met the Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas and attended a concert at which Revueltas conducted his Homage to García Lorca. Bowles took a second trip to Mexico later in 1937 in order to live for a short time in Tehuantepec (on the recommendation of Miguel Covarrubias, whom he had met in New York), where he worked on an opera about a slave rebellion.

They took a Greyhound bus to reach Mexico on their first trip together in 1937, with Bowles hiding 15,000 anti-Trotsky stickers in his luggage. In Mexico, he met the Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas and attended a concert at which Revueltas conducted his Homage to García Lorca. Bowles took a second trip to Mexico later in 1937 in order to live for a short time in Tehuantepec (on the recommendation of Miguel Covarrubias, whom he had met in New York), where he worked on an opera about a slave rebellion.

On 23 February 1938, two days after their marriage, Bowles and his wife attended the first performance of Bowles’ Mediodia (Mexican dances for 11 players) in New York. The couple then left on a honeymoon, “with 27 suitcases, two wardrobe trunks, a typewriter and a record player”, aboard a Japanese freighter, the SS Kanu Maru, on a trip that took them to Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Barbados and Paris, France. They returned to New York in September.

They visited Mexico again in 1939 and stayed in Acapulco and Taxco (where Jane first met Helvetia Perkins, who would later became her lover). On this trip, they met a still unknown Tennessee Williams, and a young man named Ned Rorem, then only a teenager, who went on to become a composer and diarist, and win a Pulitzer Prize in 1976.

Some idea of the exalted literary and musical circles in which Bowles and his wife moved can be gained from a list of their roommates in the rented house they occupied in 1941. The house, at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights, New York, was rented by the novelist and editor George Davis, who occupied the ground floor. Paul and Jane Bowles lived on the second floor, together with the theater set designer Oliver Smith. Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, and W. H. Auden shared the third floor, while Golo Mann lived in the attic. It was in this house that Bowles composed Pastorela, a Mexican Indian ballet commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein for American Ballet Caravan.

Some idea of the exalted literary and musical circles in which Bowles and his wife moved can be gained from a list of their roommates in the rented house they occupied in 1941. The house, at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights, New York, was rented by the novelist and editor George Davis, who occupied the ground floor. Paul and Jane Bowles lived on the second floor, together with the theater set designer Oliver Smith. Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, and W. H. Auden shared the third floor, while Golo Mann lived in the attic. It was in this house that Bowles composed Pastorela, a Mexican Indian ballet commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein for American Ballet Caravan.

Early in 1942, when Bowles and his wife revisited Mexico, he was taken ill with jaundice and spent several weeks in a “British hospital in Mexico City” before going to Cuernavaca for convalescence. In Cuernavaca, Jane let him read and critique her manuscript of Two Serious Ladies, though it was greatly rewritten and edited prior to its publication the following year. Jane, accompanied by Helvetia Perkins, left for New York at the end of March, while Bowles remained in Mexico a few more weeks, staying at Casa Heuer, the small posada run by siblings Paul (Pablo) and Liesel Heuer in Ajijic.

In a letter to Virgil Thomson, Bowles wrote that, “As soon as she had gone I came to Chapala. Reasons for my not going with her were several.” During his stay in Ajijic, Bowles visited the house in Chapala where D.H. Lawrence had written the first draft of The Plumed Serpent in 1923; Bowles found it “depressing” and poorly ventilated, with the ambiance of a dead-end street. According to his autobiography, Bowles discovered a whole new world of “delightful” literature during his time in Ajijic. He started with García Lorca, then read two novels by Bioy Cásares and the memoirs of Mario Alberti before turning his attention to Mexico’s early colonial times, and then to short stories by Jorge Luis Borges.

Bowles’ compositional creativity was in full flow during these years. In 1944, for example he composed the incidental music for the Broadway opening of Tennessee Williams‘ The Glass Menagerie. (The success of this work enabled Williams to spend the summer of 1945 at Lake Chapala).

Bowles’ compositional creativity was in full flow during these years. In 1944, for example he composed the incidental music for the Broadway opening of Tennessee Williams‘ The Glass Menagerie. (The success of this work enabled Williams to spend the summer of 1945 at Lake Chapala).

In 1947, Bowles moved to Tangier, Morocco. His wife, Jane, followed a year later. Except for a series of winters spent in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), and occasional trips elsewhere, Bowles lived the remaining 52 years of his life in Morocco. His fame was undiminished and a succession of famous writers and musicians made the pilgrimage to Morocco to visit him, including the most famous names of the Beat generation: Jack Kerouac, William S Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg.

When Gregory Stephenson interviewed him in Morocco in 1979, he found that Bowles had mixed memories of Mexico:

“When I mention the Tarahumara, Bowles says that he once translated some Tarahumara myths for a surrealist magazine. He rummages in his bedroom and returns with a copy of View for May 1945, a special “Tropical Americana” number which he edited. There are black and white photographs, collages and translations, including sections of the Popul Vuh and the Chilam Balam, all done by Bowles. A myth titled “John Very Bad” has been rendered by him into English from the Tarahumara. There are also bizarre and gruesome news stories selected by Bowles from the Mexican press.

Bowles speaks of the extreme poverty and squalor he encountered in parts of Mexico when he visited that country in the 1930s. Mexico was a land of gloom and chaos, he says, but also poetry, mystery and great natural beauty. Places such as Acapulco and Tehuantepec were very pleasant in those days and living there was very cheap. Yet he was often very ill in Mexico, afflicted with diverse ailments.”

The astonishingly prolific writing and composing career of Paul Bowles was drawn to a close by his death in Morocco on 18 November 1999.

Bowles’ extensive musical output included Sonata for Oboe and Clarinet (1931); Horse Eats Hat, play (1936); Who Fights This Battle, play (1936); Doctor Faustus, play (1937); Yankee Clipper, ballet (1937); Music for a Farce (1938); Too Much Johnson, play (1938); Huapango – Cafe Sin Nombre – Huapango-El Sol, Latin American folk (1938); Twelfth Night, play (1940); Love Like Wildfire, play (1941); Pastorela, ballet (1941); South Pacific, play (1943); Sonata for Flute and Piano and Two Mexican Dances (1943); ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, play (1943); The Glass Menagerie, play (1944); Jacobowsky and the Colonel, play (1944); Sentimental Colloquy, ballet (1944); Cyrano de Bergerac, play (1946); Concerto for Two Pianos (1947); Concerto for Two Pianos, Winds and Percussion (1948); Oedipus, play (1966); Black Star at the Point of Darkness (1992) and Salome, play (1993).

Novels by Bowles include The Sheltering Sky (1949); Let It Come Down (1952); The Spider’s House (1955); and Up Above the World (1966). His collections of short stories include A Little Stone (1950); The Delicate Prey and Other Stories (1950); A Hundred Camels in the Courtyard (1962); Things Gone & Things Still Here (1977); Collected Stories, 1939–1976 (1979); and A Thousand Days for Mokhtar (1989). Poetry works by Bowles include Two Poems (1933); Scenes (1968); The Thicket of Spring (1972); Next to Nothing: Collected Poems, 1926–1977 (1981); and No Eye Looked Out from Any Crevice (1997).

Sources:

- Paul Bowles. 1972. Without Stopping: An Autobiography. Peter Owen Publishers.

- Virginia Spencer Carr. 2004. Paul Bowles: A Life. Scribner.

- The authorized Paul Bowles website.

- Letter from Paul Bowles to Virgil Thomson (Mexico, April 1942). Jackson Music Library, Yale University, Virgil Thomson archive.

- Gregory Stephenson. 1979. “Calling on Paul Bowles, Tangier, Morocco, August 1979”

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

I would kindly point out, as other online web site fail to do, that Mr. Bowles received the Pulitzer Prize for his breakout novel The Sheltering Sky.

Thank you

PS My mother Liliane Webb, the Author of the Book The Marranos, myself and my brother lived in Tangier for one year during the year 1969. An incredible experience as a child for certain! I do remember my mother attended social events at the Bowles’s house quite often.

Dear Dr Smith, Thanks for your interesting comment and sharing a personal memory. I have seen previous references to the Pulitzer claim, but Mr Bowles’s name does not appear on a search of nominations and prize winners at https://www.pulitzer.org/. Regards, TB.