Tobias (“Toby”) Schneebaum (1922-2005) was a gay artist, author, adventurer and activist, best known for living among, and documenting, the Amarakaeri people of Amazonian Peru and the Asmat people of the southwestern part of the island of New Guinea.

Before these trips into the tropical jungle, Schneebaum had lived in Ajijic for several years, and had experienced his first taste of tropical jungle by visiting the reclusive Lacandón people in Chiapas.

Schneebaum’s life and legacy to anthropology have been analyzed at length by later writers who have placed most emphasis, quite rightly, on his adventurous exploits in distant jungles, and on his humanitarian, activist work in New York City in connection with HIV/AIDS.

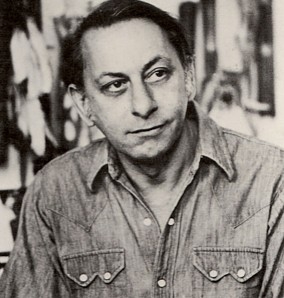

Tobias Schneebaum. 1970s. (New York Observer)

This post focuses on Schneebaum’s formative years in Ajijic, immediately before he began his major travels. His three years at Lake Chapala undoubtedly left their mark on the young man. Schneebaum later wrote at some length about his time in Ajijic in two of his memoirs: Wild Man (1979) and Secret places: my life in New York and New Guinea (2000). Unfortunately, these two accounts contain some factual inaccuracies and sometimes conflict with one another, making it difficult to reconstruct with certainty the details of his time in the village.

Theodore Schneebaum (his birth name) was born to Polish immigrants in New York on 25 March 1922 and raised in the Jewish faith in Brooklyn. After attending Stuyvesant High School, he studied at the City College of New York, where he gained a B.A in Mathematics and Art.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Schneebaum joined the U.S. army and became a radar mechanic. After the war, he took evening painting classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School with Mexican muralist Rufino Tamayo. Schneebaum was underwhelmed by Tamayo’s teaching but did follow his advice to pursue his artistic dreams in Mexico rather than Paris.

In either 1947 or 1948, Schneebaum headed for Mexico City. In Wild Man, Schneebaum recalls living for a time at a pension called Paris Siete, where political painters such as Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros (who “liked my paintings”) met every week.

Schneebaum first visited Ajijic in the company of “Madame Sonja”, an elderly “Rumanian osteopath” who he accompanied when she traveled from Mexico City to Lake Chapala to treat Zara Alexeyeva Ayenara, who had recently lost her “adopted brother, a Russian who had been a great dancer”. (New York-born Zara and her Danish dance partner, Holger Mehner, lived at Lake Chapala for years and were known locally as the “Russian dancers”.) In Wild Man, Schneebaum claims that Sonja’s patient was Zara, but in Secret Places he mistakenly says it was “Holga Menha” (which is impossible since Holger had died in 1944).

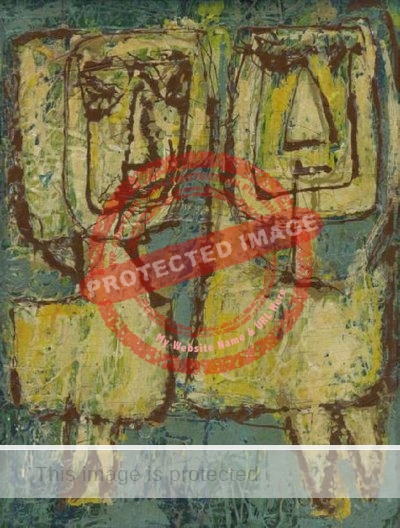

Schneebaum landed on his feet in Ajijic and it became his base for the remainder of his time in Mexico, including trips to southern Mexico and the one in 1950 to visit the Lacandón Maya in Chiapas. Like many other artists who have visited Ajijic, Schneebaum’s own artistic output during his stay in the village was greatly influenced by his discovery of pre-Columbian motifs and statues.

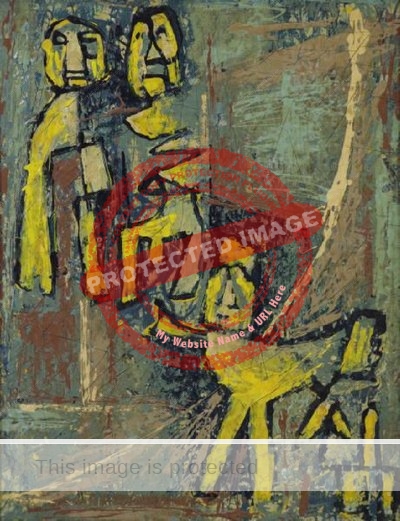

Tobias Schneebaum. Undated. Abstract (Sold by Clarke Auction Gallery, 2017)

Schneebaum also taught art for several weeks each summer and encountered a variety of local and international artists in the village, who formed the nucleus of an active social circle. Moreover, as David Bergman, in his foreword to Secret Places, writes, “Schneebaum had refrained from sex after some adolescent experiences; now in the Mexican town of Ajijic, his homosexual desires were reawakened.”

In fact, these three main facets of his life in Ajijic – art, friends and sexual reawakening – were intimately intertwined shortly after being employed by Irma Jonas to teach students attending her summer painting schools in Ajijic (which were held from 1947 to 1949 inclusive). Jonas also appointed a second American artist, Nicolas Muzenic, and a Mexican artist, Ernesto Butterlin (who adopted the surname Linares), to share the classes. The three became fast friends.

In his memoirs, Schneebaum describes Ernesto (whom he refers to as “Lynn”) in glowing detail: “A young blond painter, born in Guadalajara of German parents, also lived in Ajijic. He was twenty-seven, blue-eyed, four inches over six feet, and very handsome, and was subject to the attentions of both the men and the women who later passed through town… He was engaging and irresistible; he was slender and deeply tanned and had just the right amount of softness to his body and mind so that he threatened no one.”

According to Schneebaum, an ill-fated love triangle developed between the three artists. Schneebaum fell in love with Nicolas Muzenic, who fell in love with Lynn. Matters were complicated by the arrival of “haughty and radiantly beautiful” Zoe, the “fourth member of our group”, who had been living with Henry Miller in Big Sur when she heard about Lynn and decided to visit Ajijic. Zoe “wore sheath dresses of black or white and penciled dark lines around her eyes to shape them into almonds, and enlarge the black pupils. Her skin was pale, the color of pearls.”

To further complicate their relationships, Zoe became obsessed with Nicolas who “arranged her hair in various styles and coated her face with makeup and sequins”. After dinner, “they would dance with their slender bodies tightly together, moving to slow foxtrots and tangos, dipping deeply, and turning with grace.”

Schneebaum recalls in Wild Man that, “Lynn’s casual ways bewitched and irritated Nicolas, just as Nicolas’s arrogant, snobbish manner attracted and mortified Lynn. Nicolas moved into Lynn’s house and began a frenzied, volcanic affair that lasted two years”, ending (according to Schneebaum, though it sounds somewhat fanciful) with Nicolas buying the property and forcing Lynn to move out.

Katie Goodridge Ingram was living in Ajijic at the time and knew this quartet of extraordinary individuals. She remembers Zoe as “one of the most stunningly beautiful woman you could ever see. She slathered coconut oil all over and then went down to the (then) wonderful old stone pier and tanned herself generously for hours. Toby joined her, and Lin and sometimes Nick Muzenik. All of them gorgeous. Well, Toby was quiet, shy, introverted, and stooped, so was not so dramatically attractive.”

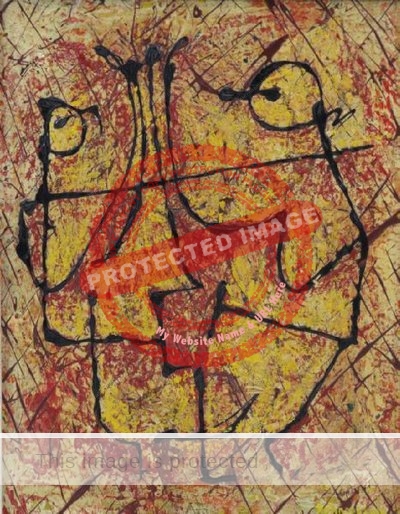

Tobias Schneebaum. Undated. Abstract (Sold by Clarke Auction Gallery, 2017)

Recalling one of the summer schools he taught at, Schneebaum writes in Wild Man that, “Irma [Jonas] sat with her twenty-six students, only two of whom were male. They stayed in Ajijic six weeks, loved it all, and were very generous with everyone. I received an offer from the aged wife of a Hollywood producer to live with her and two swimming pools in Bel Air.” This number of students does not tally with that provided by Jonas in an article written much closer to the time, but Schneebaum’s description presumably applied to the 1949 workshop, the last of Jonas’ painting schools to be held in Ajijic. The following year, she moved the classes to Taxco. (Incidentally, the students at the summer 1949 workshop in Ajijic included the African American playwright, artist and author Lorraine Hansberry.)

In his two memoirs, Schneebaum mentions various other residents of Ajijic, including authoress Neill James, the Johnsons (Herbert and Georgette), “an elderly British couple” who “had a splendid garden with hundreds of blossoming hibiscus”, and “Herr Müller and Fräulein Müller”, a German brother and sister who ran the village’s only small pension, though “They were nondescript and almost never talked to each other or to any of the guests.” Despite staying at their pension for several months, Schneebaum has recalled their names inaccurately since he is clearly describing Pablo and Liesel Heuer.

While he was in Mexico, Schneebaum (in Secret Places) claims to have had “one-man shows in Mexico City and Guadalajara with the help of Carlos Mérida” but I have been unable to find any supporting evidence or details for these in the local press or elsewhere.

He did, however, participate in at least two group shows in Jalisco. The first, held at the Museo del Estado (Regional Museum) in Guadalajara in March 1949, was of abstract works by “four Ajijic artists”: Schneebaum, Louise Gauthier, Ernesto Linares (Ernesto Butterlin) and Nicolas Muzenic and Guadalajara-based Alfredo Navarro España. Later that year, in August, a group show at the Villa Montecarlo in Chapala featured works by Schneebaum, Muzenic, Alfredo Navarro España, Shirley Wurtzel, Ann Woolfolk and Mel Schuler.

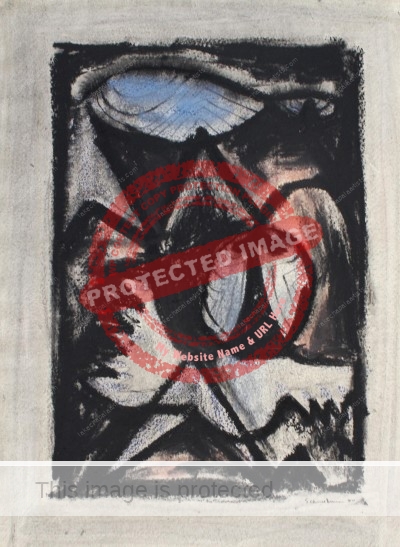

This abstract multi-media (pastel, watercolor, ink and pencil) drawing (below) by Schneebaum dates back to his time in Mexico and is currently listed for sale at DallasModerne.

Tobias Schneebaum. 1950. Multi-media abstract (DallasModerne)

After Ajijic and his trip to the Lacandón in 1950, Schneebaum returned to the U.S. where, in 1953, he held his first one-man art show at the Ganso Gallery in New York. After that gallery closed, Schneebaum was taken on by the Peridot Gallery which staged solo shows of his work in 1955, 1957, 1960, 1964 and 1970.

Between about 1954 and 1970, Schneebaum was alternating travel to distant places with a job as designer at Tiber Press, a silk-screen greeting-card company in New York that also occasionally published books. This was when, according to journalist Robin Cembalest, Schneebaum moved into an apartment next door to Norman Mailer. The two became good friends. Mailer and Adele (soon to become his second wife) had also spent some time in Ajijic. After they returned from Mexico and became engaged, “Schneebaum made an accordion-shaped announcement for the engagement… when unfolded, it revealed a long penis.”

In 1954, Tiber Press published a curious limited edition children’s book entitled The Girl in the Abstract Bed. This has delightfully whimsical text by Vance Bourjaily, accompanied by genuine silkscreen prints of watercolors by Schneebaum that were tipped in before the book was bound. Clearly the two men were close friends (Bourjaily himself spent most of 1951 in Ajijic) and the book’s title came from the name of an abstract painting that Schneebaum had done for Vance and his first wife, Tina, to beautify the headboard of their daughter Anna’s crib.

In 1955, Schneebaum was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to travel and paint in Peru, an epic journey recounted in his 1969 memoir Keep the River on Your Right. The book, which became a cult classic, included the sensational story of how, while in the Amazon, he had been forced to participate in cannibalism.

Tobias Schneebaum. Undated. Abstract (Sold by Clarke Auction Gallery, 2017)

On other extended trips, Schneebaum explored Europe, crossed the Sahara desert, and ventured into the Congo, Ethiopia and Somalia before completing an overland crossing of Asia from Istanbul to Singapore, Borneo and the Philippines. In 1973, he lived for months with the Asmat people on the southwestern coast of New Guinea. This indigenous group became the focus for the next 25 years of his life. He helped establish the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress, went back to school to complete an M.A. degree in Cultural Anthropology from Goddard College in 1977, and was a lecturer on cruise ships to the region.

In 1999, Schneebaum was persuaded by film-makers Laura and David Shapiro to revisit New Guinea and Peru for a documentary film, entitled Keep the River on Your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale, released in 2000. He spent the final years of his life in Westbeth Artists Community in Greenwich Village, New York City, and died, after a lengthy battle with Parkinson’s, in Great Neck, New York, on 20 September 2005.

Schneebaum left his collection of Asmat art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and his personal papers to the University of Minnesota, where they are part of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies. His written legacy includes Keep the River on Your Right (1969); Wild Man (1979); Asmat Images, The Asmat Museum of Culture & Progress (1985); Where the Spirits Dwell (1989); Embodied Spirits (1990) and Secret Places: My life in New York and New Guinea (2000).

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Gail Eiloart and Katie Goodridge Ingram for sharing with me their personal memories of Tobias Schneebaum.

Sources

- Robin Cembalest. 2001. “Call of the Wild: What made Tobias Schneebaum traverse the globe in search of cannibals, leaving everything behind except his sketch pad?” ARTnews, March 2001.

- Dylan Foley. 1999. “Literati Ex-Cannibal on Film” (Tobias Schneebaum Interview), New York Observer, 2 November 1999. Reprinted on Last Bohemians blog.

- Martin Goodman. 2005. “Tobias Schneebaum – Artist who went to live with cannibals” (obituary), The Independent (London), 29 Sep 2005.

- Tobias Schneebaum. 1979. Wild Man. Viking Press.

- Tobias Schneebaum. 2000. Secret Places: My life in New York and New Guinea. (University of Wisconsin). (Foreword by David Bergman)

This profile was first published 5 January 2017.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcomed. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Tony Burton’s books include “Lake Chapala: A Postcard History” (2022), “Foreign Footprints in Ajijic” (2022), “If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants” (2020), (available in translation as “Si Las Paredes Hablaran”), “Mexican Kaleidoscope” (2016), and “Lake Chapala Through the Ages” (2008).

Mr. Burton: I just discovered your article April 13, 2024; Toby Schneebaum was my very dear friend and companion for many years, mostly in New York. However I supported him on his journeys, was acknowledged in his book, and received many of his drawings, paintings, and tribal items over the years. While the Documentary of his Life was being filmed in Peru I was in Venezuela and although we tried to connect, I couldn’t get over the Andes..We last had dinner in his apt at Westbeth shortly before he died. Since I have all his books, in various editions, I tried to download and/or copy your article–to compare corrections with the printed books cited– without success, because you have it ‘disabled. Can you, as a favor, disable this? I would much appreciate it. Thank you in advance for this… David Burke PS: I lived in Mexico for some years, spent time at Lake Chapala & Ajiijc as well as in Chiapas and the Yucatan (and else where in South America). Floriano Vecchi, founder of Tiber Press, was also a dear friend of mine.

David, Thanks for your very interesting comment. I’ll respond shortly via email. TB