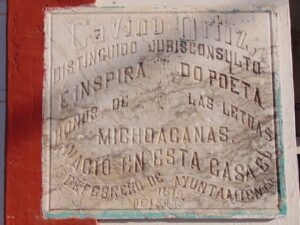

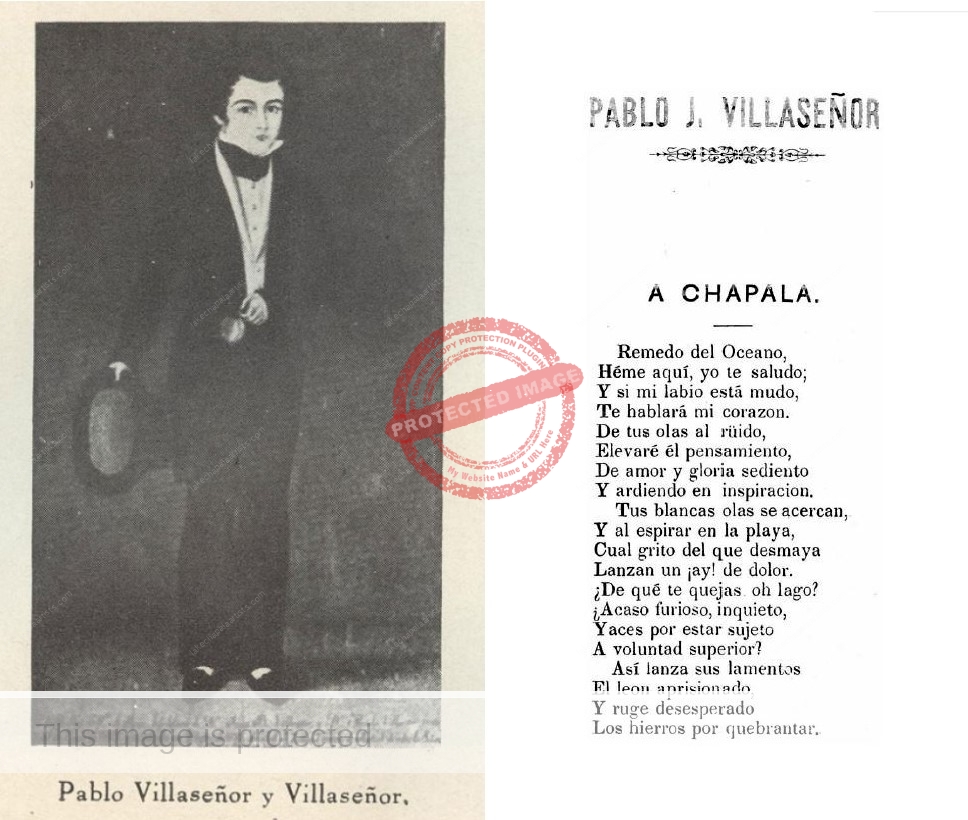

Despite Pablo J. Villaseñor’s tragically short life—he died in 1855 at the age of 27—he has left us some memorable literature, including an evocative romantic poem about Lake Chapala, an entry about Chapala in Mexico’s multi-volume, Diccionario Universal de Historia y Geografía, and a play with its own Wikipedia page.

Pablo José María Villaseñor Villaseñor was born 14 January 1828 in Guadalajara, and baptized there at Templo de Nuestra Señora del Pilar three days later. Villaseñor’s family owned the Hacienda de Cedros in Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos, so he would have been very familiar with Lake Chapala from an early age. He began studies at the Seminario Conciliar de Guadalajara in 1837.

His literary career began in 1846 when he started writing for a newspaper called El Látigo. He later also wrote for Voz de Alianza, and was a founder member of the Sociedad Literaría La Falange de Estudio.

On 19 February 1849 at the age of 21, Villaseñor married Petra Ignacia Garcia Camberos (1833-1911) at the Santuario de Guadalupe in Sayula, Jalisco. (Their son, Juan Villaseñor, was born the following year; he married in Guadalajara in 1877.) A few months after marriage, Villaseñor accepted the (largely honorary) title of abogado.

Villaseñor had a very active literary career, writing in various genres, and participating in various literary groups and magazines. In 1851, he contributed 16 poems to a collection he helped organize titled Aurora poética de Jalisco: colección de poesías líricas de jóvenes jalisciences, dedicada al bello sexo de Guadalajara (Poetic Dawn of Jalisco: a collection of lyrical poems by young people from Jalisco, dedicated to the fair sex of Guadalajara), published in Guadalajara by J. Camarena.

His emotive poem titled A Chapala (To Chapala), written in 1851, portrays the lake as a living, breathing entity, with sentiments such as love, longing, pain and melancholy, a stage for both remembered and untold stories of heroes and former glories.

Here’s an informal English translation of a sample stanza from the middle of the poem:

Time flies. What remains

Of the gloomy monastery?

Rubble, oh! and mystery,

The grass that grows there!

And the tombs of the heroes,

Forgotten among the sand;

And the sacred walls,

Made nests for reptiles.

Pablo Villaseñor died at the family’s Hacienda de Cedros on 13 November 1855.

Shortly after the poet’s death, historian Agustín Rivera y Sanromán (1824-1916), a long-time friend of the Villaseñor family, spent two weeks at Hacienda de Cedros. In a footnote in his 1910 life of Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, Rivera noted that the “Villaseñor family of Guadalajara” had owned Cedros (which dates back to the sixteenth century) since “long before 1810″ and then described the family dining table:

I had the pleasure of eating at the dining room table, which had recently been restored and was worthy of a museum. It is large, made of unpainted wood, and the owners have been curious enough to inscribe on it the names of people who have eaten there. There I read the names of Bishop Mayor, Bishop Cabañas, Father Hidalgo, Archbishop Espinosa, and others. One of the respectable people with whom I dined is Mrs. Ignacia Garcia, widow of my friend the poet and lawyer Don Pablo J. Villaseñor.”

According to Enrique Palomar, the name of Primitivo Ron was also carved into the Villaseñor family dining table, because he had taught the hacienda owner’s only son, Lorenzo, while employed as a teacher in the local village school in Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos. Primitivo Ron gained infamy some years later in 1889 when he assassinated General Ramón Corona, the Governor of Jalisco, whose name is apparently also carved in this historic table.

Guillermo Romo was a close friend of the Villaseñor family. In a 1945 article, he included a previously unpublished biographical recollection of the poet’s life written by Clemente Villaseñor in 1858, in which he explained that, because Pablo Villaseñor,

was very ill and suffered from aneurysms, the applause of the public and the opinion they formed about his compositions—favorable or adverse—greatly affected him and sometimes he fell bedridden. He was very satirical in his private conversations.”

Villaseñor’s entry about Chapala for Mexico’s nineteenth-century Diccionario Universal de Historia y Geografía will be considered in a separate post.

And the Wikipedia page? Villaseñor’s most famous three-act drama, a tragedy based on historical events in Guadalajara, is El Palacio de Medrano: Drama en Tres Actos y en Verso, published in 1851, which (for some reason) has its own English language Wikipedia page.

Sources

- Juan R. Navarro (publisher). 1853. Guirnalda poetica: selecta colección de poesias mejicanas. Mexico: Imprenta de Juan R. Navarro.

- Enrique Palomar. 1982. “Una Mesa con Historia.” El Informador: 4 July 1982, 11.

- Agustín Rivera. 1910. Anales de la Vida del Padre de la Patria Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. León, Guanajuato: Imprenta de L. López.

- Guillermo Romo Celis. 1945. “Una visita a Cedros, solar de los Villaseñor.” pp 61-87 of Indice de las Memorias de la Academia Mexicana de Genealogia y Heraldica, Tomo I, No. 1 (marzo de 1945), pp 61-86. Romo Celis cites a document written by Clemente Villaseñor, dated 6 October 1858.

Comments, corrections and additional material are welcome, whether via comments or email.

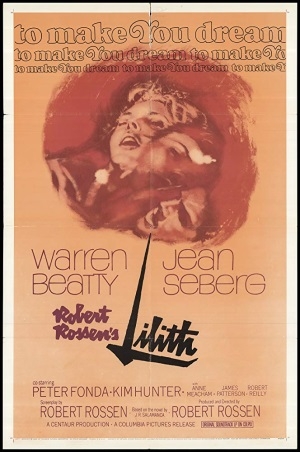

Richard Wendell Phillips Jr., the son of a New York stage actor, Wendell K. Phillips (1907-1991), and his first wife, Odielein Pearce, was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1929 and died on 2 October 2010. After graduating from Staunton Military Academy in Virginia in 1948, he planned to enter the U. S. Military academy at West Point. He later became an actor and played an uncredited part as a patient in Lilith (1964), written and directed by Robert Rossen.

Richard Wendell Phillips Jr., the son of a New York stage actor, Wendell K. Phillips (1907-1991), and his first wife, Odielein Pearce, was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1929 and died on 2 October 2010. After graduating from Staunton Military Academy in Virginia in 1948, he planned to enter the U. S. Military academy at West Point. He later became an actor and played an uncredited part as a patient in Lilith (1964), written and directed by Robert Rossen.