The following excerpts come from the detailed account written by Dr. Leo Leonidas Stanley (1886-1976) after visiting Lake Chapala in October 1937. (For ease of reading, accents and italics have been added and spelling standardized.)

Note that early descriptions (in English or Spanish) of the villages on the south shore of the lake are exceedingly rare, making Stanley’s account especially valuable.

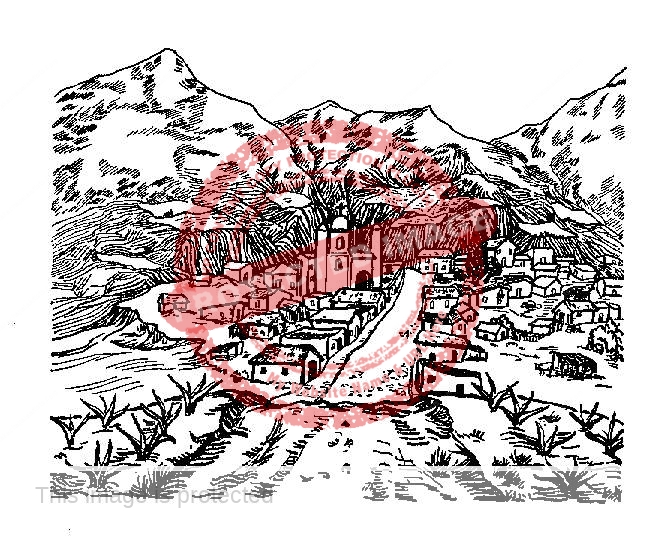

San Luis Soyatlán

Our next objective was San Luis Soyatlán, the Cathedral spires of which town we could see at a long distance. In the flat Mexican villages, the church always stands out prominently. There were a number of smaller vi11ages, at which we stopped for a few moments, and at one place we were able to get some beer. The Mexican girl who served us was a rather pretty señorita, and evidently a friend of Ramón’s. She had not seen him for several weeks, and greeted him in a very friendly manner. As Ramón was not married, Alonzo and I began to josh him a little and accused him of liking the girls. This seemed to please him very much.

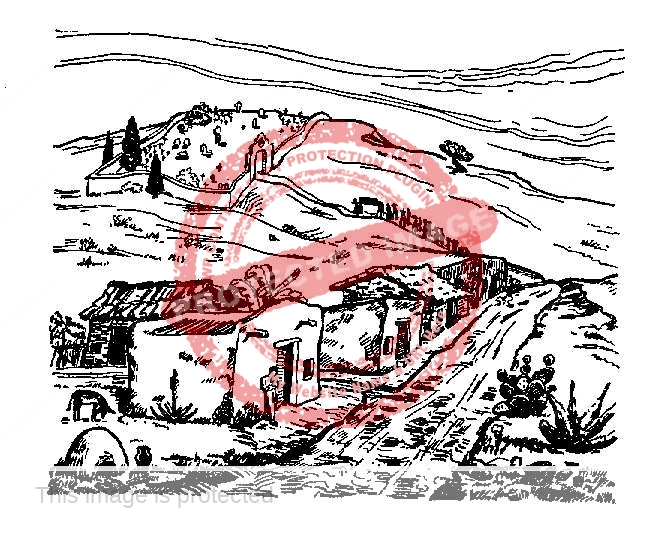

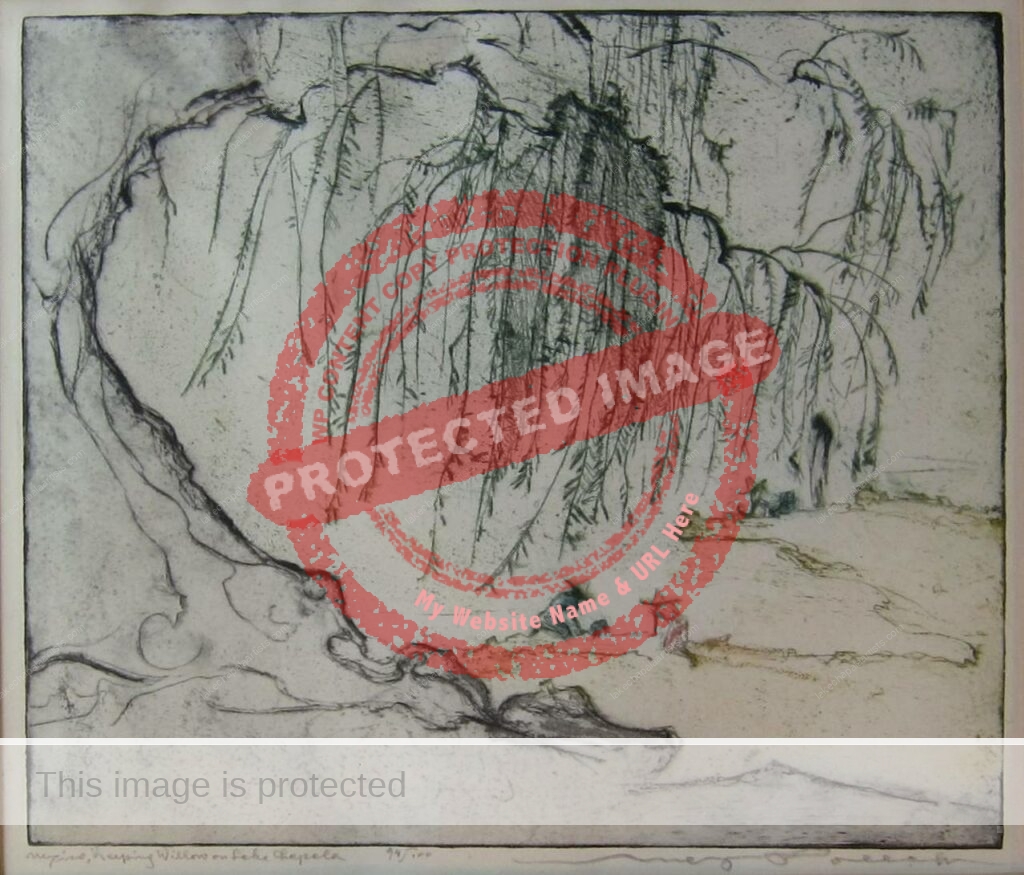

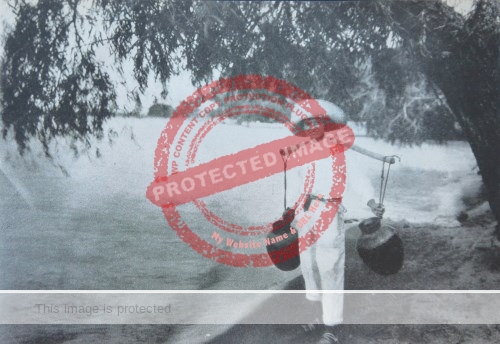

Leo Stanley. 1937. Post Office on south shore of Lake Chapala. Reproduced by kind permission of California Historical Society.

In going through one village, we saw the post office. On a blackboard in front of it were the names of those for whom a letter was waiting. This did not seem to be a very bad idea.

Far out in the country we came across a young Mexican who was hunting. He was looking for doves, or pa1omas. He had a muzzle-loading shotgun, and carried his powder and caps in a container made of a cow’s horn. It was an interesting old weapon, and was made in 1850. The date was on the barrel. He offered to sell it to me for ten pesos, which is about three dollars, but it would have been difficult to transport, and I had to refuse this old relic. [56-57]

At this point, Stanley realized that his original plan to ride all the way around Lake Chapala was impossible in the time he had available. He decided to stay overnight in San Luis Soyatlán and then ride on the next morning to Tuxcueca in time to catch the daily boat to Chapala, leaving Ramón to “retrace our steps with the animals.”

They reached San Luis by mid-afternoon and found somewhere to stay. While the others finished their meal in a fonda which had “large quantities of flies,” Stanley strolled down to the lake shore:

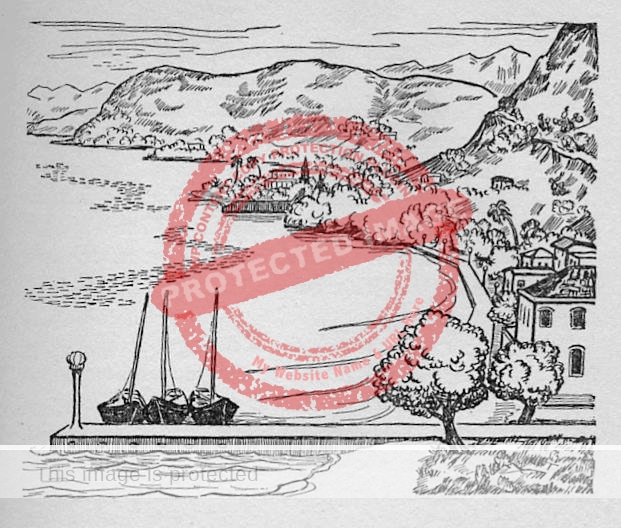

It was a very pretty afternoon, and off in the distance across the lake toward San Juan could be seen a peculiar phenomenon. By landslides and erosions in the mountains, the natural form of a spread eagle was displayed in brown against the green verdure. This marking could be seen very distinctly from the southern shore of the lake.

Because of road building activities around San Luis there are a number of new trucks being used. One of the drivers had directed his new Chevrolet truck into the water along the shallow margins of the lake, and was giving it a very thorough cleaning. He took as much care of his truck as the ordinary private chauffeur of his owner’s limousine. As he polished, he sang, and seemed to enjoy the occupation very much. [58-59]

Upon returning, I stopped at a number of the Spanish houses along the street, and there saw the women and some of the children weaving material for hats, or sombreros. A very tough reed is used. It is woven into strips about half and inch wide, the women work very deftly with their fingers, and area able to braid the reeds without even looking at them. These strips are then rolled up as much as one would roll a tape, and are then sent to a central shop where the hat maker forms them into the sombreros. This headgear is very durable, and serves the purpose of keeping off the rain as well as the tropical sun.

The following morning (13 October 1937) they rode on towards Tuxcueca:

We rode on out through the town, and toward the east… During the middle of the forenoon, we arrived at an adobe school house which overlooked the lake. We went in and found the maestra, or teacher, quite friendly and highly pleased that anyone should care to visit her school. She apologized for the appearance of the place, but it really was quite tidy and comfortable. The children were delighted to line up for their pictures. One child had absolutely no clothing on at all, but the others had enough to cover their nakedness. [63]

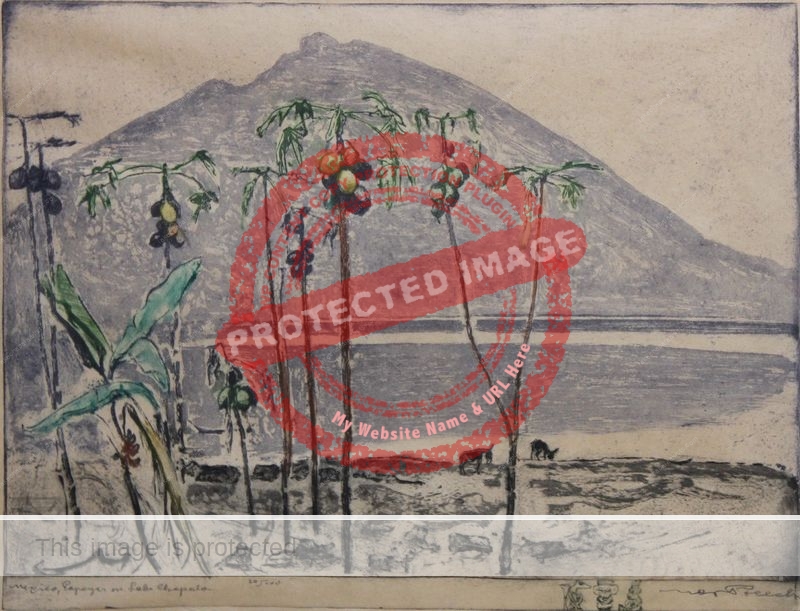

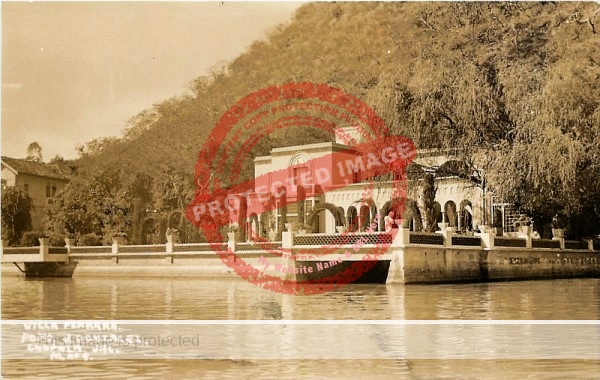

Leo Stanley. 1937. Shore of Lake Chapala. Reproduced by kind permission of California Historical Society.

When they reached Tuxcueca, Stanley was asked if he would see two girls who were quite ill:

It was about two cuadras, or blocks, away. The captain of the boat said that he would hold the launch for me. This house was a make-shift hospital, and run by a practical nurse.

There were two girls in a very dark room, one aged seventeen, and the other about eleven. Both were ill with pneumonia, and the small one’s lungs were almost entirely congested. She was comatose, and I felt that the end was not far away. There was very little that I could do under the circumstances, but I gave them some instructions, which they seemed to appreciate. They asked for a bill for my services, but of course I told them that there was no charge.

While we were waiting on the stone pier for the departure of the boar, four or five burros were driven to the eater’s edge to unload their burdens. These little animals each had four or five immense planks which they had carried from forests across the mountains. Each load must have weighed between three and four hundred pounds.

A few minutes later, Stanley and Alonzo took the gasoline boat—described as “about forty feet long, fairly narrow, and made of metal”— back to Chapala, arriving just in time to enjoy a late lunch.

Source

- Leo L. Stanley. “Mixing in Mexico”, 1937, two volumes. Leo L. Stanley Papers, MS 2061, California Historical Society. Volume 2.

Acknowledgments

My heartfelt thanks to Frances Kaplan, Reference & Outreach Librarian of the California Historical Society, for supplying photos of Stanley’s account of his time at Lake Chapala. I am very grateful to Ms Kaplan and the California Historical Society for permission to reproduce the extracts and photos used in this post.

Comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios are welcome. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”

Seaton wrote that, “In the little Indian town of Ixtlahuacan [de los Membrillos], they make a famous quince wine. It is good, if you like it, but rather sweet, and more like a cordial.”

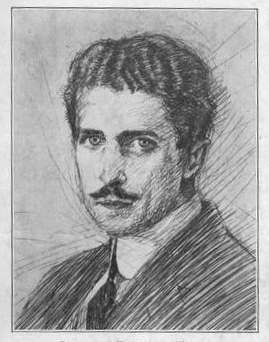

![l to r: Robert Hunt, Galdys Ficke, Arthur Ficke, ca 1935. [Source: Kraft: "Who is Witter Bynner"?]](http://lakechapalaartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/hunt-robert-with-fickes-chapala-1934-5s.jpg)

Chapter 11 is about a religious procession to the cemetery (campo santo) on the hillside:

Chapter 11 is about a religious procession to the cemetery (campo santo) on the hillside: