Several Lake Chapala websites boast that the talented and multifaceted American author Norman Kingsley Mailer (1923-2007) is among those writers who found inspiration at the lake. But is their pride in his visits to the area misplaced? Mailer’s biography has been exhaustively documented in dozens of books and there is no doubt he is a great writer. However, this post concentrates on the less savory side of his visits to Ajijic and Lake Chapala. Is he really someone local residents should be proud of?

According to normally reliable sources, Mailer visited the area more than once in the course of his illustrious career. Mailer’s first visit to Lake Chapala was in the late 1940s with his first wife, Beatrice Silverman. Journalist Pete Hamill referred to this visit in his “In Memoriam” piece about Mailer:

“Moulded by Brooklyn and Harvard and the Army (he served as an infantryman in the Philippines in World War 2), he erupted onto the literary scene in 1948 with “The Naked and the Dead”, the first great American novel about the war. For the first time, he had money to travel and hide from his fame. He went to Paris where he succumbed to the spell of Jean Malaquais, the critic and novelist. He went to Lake Chapala, where he did not succumb to the charms of the American expatriates.”

This is presumably the occasion referred to by Michael Hargraves when he wrote dismissively that Mailer “only passed through Ajijic back in the late 1940s to have lunch”.

While Mailer may not have fallen immediately in love with Lake Chapala and its American expatriates, he certainly grew to love Mexico and spent several summers in Mexico City during the 1950s. In July 1953, and now with painter Adele Morales (who became his second wife the following year) in tow, Mailer was renting a “crazy round little house” a short distance outside Mexico City, in the Turf Club (later the Mexico City College). Mailer described the house in a letter that month to close friend Francis Irby Gwaltney :

“At the moment we’re living at a place called the Turf Club which is a couple of miles out of the city limits of Mexico City in a pretty little canyon. We got a weird house. It’s got a kitchen, a bathroom, a living room shaped like a semicircle with half the wall of glass, and a balcony bedroom. It looks out over a beautiful view and is furnished in modern. This is for fifty-five bucks a month.”

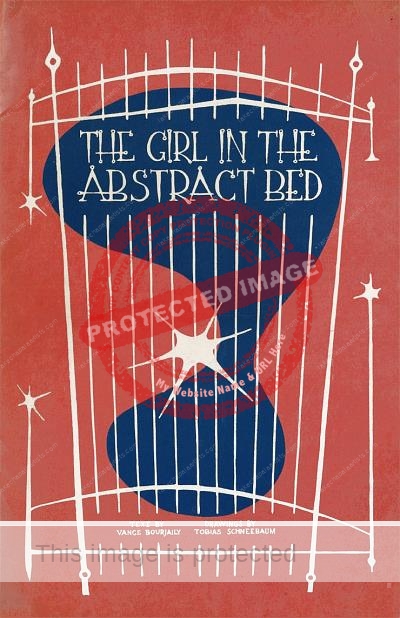

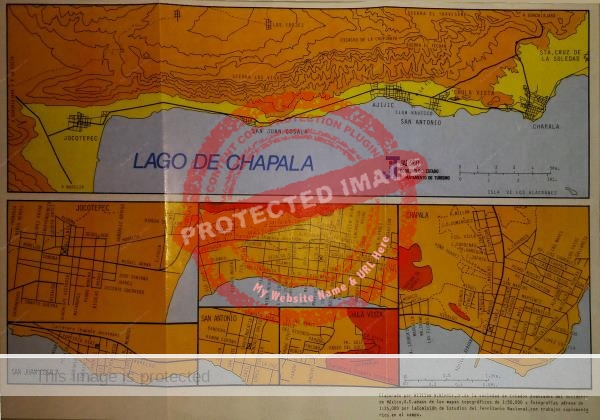

In another letter (dated 24 July 1953) from the Turf Club, Mailer was clearly referring to Ajijic when he wrote that “There are towns (Vance was in one) where you can rent a pretty good house for $25 a month and under.” Mailer was referring to novelist Vance Bourjaily, a long-time friend who lived and wrote in Ajijic in 1951.

In October 1953, Mailer was guest speaker at the Mexico City College (then in its Colonia Roma location) at the fall session opening of its Writing Center, along with Broadway producer Lewis Allen. Bourjaily also gave lectures at the Mexico City College.

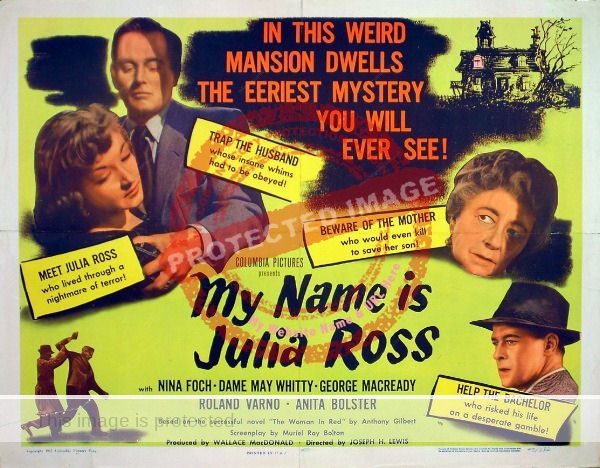

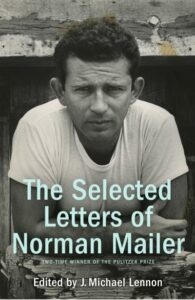

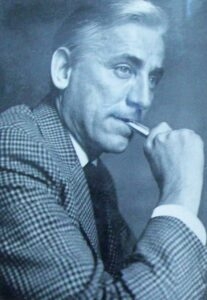

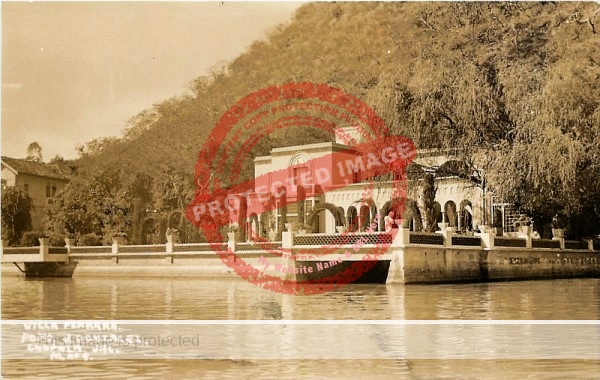

Norman Mailer book cover

By a not-entirely-surprising coincidence, one of the owners of Turf Club property at that time was John Langley, a former concert violinist living on insurance payouts following a shooting accident that had cost him the index finger of his left hand. During the 1950s, Langley spent most of his time at his lakefront home in Ajijic. (The 1957 Life Magazine article about the village includes a photograph of Langley, at his Ajijic home, relaxing with Jeonora Bartlet, who later became the partner of American artist Richard Reagan). Langley and Mailer definitely knew each other and more than likely shared the odd joint.

Struggling to complete a worthy follow-up novel to The Naked and the Dead, Mailer found that smoking pot gave him a sense of liberation. Biographer Mary V. Dearborn quotes Mailer as writing that, “In Mexico… pot gave me a sense of something new about the time I was convinced I had seen it all”.

She then connects this to Mailer’s cravings for sexual experimentation:

“But it was also bringing out a destructive, event violent side to his nature. Friends have recalled some ugly scenes in Mexico and hinted at sexual adventures that pressed the limits of convention as well as sanity.”

In 1955, Mailer co-founded The Village Voice (the Greenwich Village newspaper in New York on which long-time Lake Chapala literary icon and newspaper editor Allyn Hunt later worked) and in the late 1950s or very early 1960s, Mailer and Adele were back in Mexico, living for some months in Ajijic.

In his obituary column, Hunt described how Mailer “discovered weed when he lived in Greenwich Village” and then “began using marijuana seriously”, before asserting that when Mailer and Adele “landed in Ajijic, their consumption of grass and their sexual games continued.” This is supported by Mack Reynolds, another journalist and author living in Ajijic at about that time. In The Expatriates, Reynolds, who eventually settled in San Miguel de Allende, recounts a more-than-somewhat disturbing story told him by the aforementioned John Langley:

“A prominent young American writer, who produced possibly the best novel to come out of the Second World War, had moved to Ajijic with his wife. His intention was stretching out the some $20,000 he had netted from his best seller for a period of as much as ten years, during which time he expected to produce the Great American Novel. However, he ran into a challenge which greatly intrigued him. Their maid was an extremely pretty mestizo girl whose parents were afraid of her working for gringos. They had heard stories of pretty girls who worked for Americans, especially Americans in the prime of life, and our writer was still in his thirties. Still, the family needed the money she earned and couldn’t resist the job. After the first week or two, the maid revealed to the author’s hedonistically inclined wife that each night when she returned home her parents examined her to discover whether or not she remained a virgin.

To this point the author hadn’t particularly noticed the girl, but now he was piqued. The problem was how to seduce her without discovery and having the authorities put on him by the watchful Mexican parents. He and his wife consulted with friends and over many a rum and coke at long last came up with a solution.

The girl, evidently a nubile, sensuous little thing, which probably accounted for her parents’ fear, was all too willing to participate in any shenanigans, especially after she’d been induced to smoke a cigarette or two well-laced with marijuana. The American author and his wife procured an electrical massage outfit of the type used by the obese to massage extra pounds off their bodies. They then stretched the girl out on a table, nude, and used the device on her until she was brought to orgasm over and over again.”

These brief descriptions of Mailer’s visits to Lake Chapala suggest that websites may like to rethink his inclusion on their list of the great writers inspired by the lake and its friendly communities. Mailer clearly pushed the bounds of friendship well beyond the reasonable. (Perhaps a Mailer biographer reading this can pinpoint precise dates for Mailer’s visits, and suggest some of his more positive contributions to the area?)

Mailer does have at least one additional connection to Ajijic via the Scottish Beat novelist Alexander Trocchi (1925-1984), who worked on his controversial novel Cain’s Book (1960) in Ajijic in the late 1950s. Shortly after its publication, and live on camera in New York, Trocchi shot himself up with heroin during a television debate on drug abuse. Already on bail (for having supplied heroin to a minor), and with a jail term seemingly inevitable, Trocchi was smuggled across the border into Canada by a group of friends (Norman Mailer included), where he took refuge in Montreal with poet Irving Layton.

Mailer’s novels include The Naked and the Dead (1948); Barbary Shore (1951); The Deer Park (1955); An American Dream (1965); Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967); The Executioner’s Song (1979); Of Women and Their Elegance (1980); Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1984); Harlot’s Ghost (1991). He also wrote screenplays, short stories, poetry, letters (more than 40,000 in total), non-fiction works and several collections of essays, including The Prisoner of Sex (1971).

Norman Mailer won a Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction with The Armies of the Night (1969) and a Pulitzer for Fiction with his novel The Executioner’s Song (1980).

Sources:

- Anon. 1953. “Writers hear Mailer speak”, in Mexico City Collegian, Vol 7 #1, p1, 15 October 1953.

- Mary V. Dearborn. 2001. Mailer: A Biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Pete Hamill. 2007. In Memoriam: Mailer y Norman. (Published, translated into Spanish in Letras Libres, December 2007, pp 42-44.

- Michael Hargraves. 1992. Lake Chapala: A literary survey (Los Angeles: Michael Hargraves).

- Allyn Hunt. 2007. “Norman Mailer, Contentious Author And Provocateur Who Died A Death He’d Have Scoffed At…”, Guadalajara Reporter 23 November 2007

- J. Michael Lennon (editor) 2014. Selected Letters of Norman Mailer. Random House.

- Mack Reynolds. 1963. The Expatriates. (Regency Books, 1963)

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts, or email us.

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).

His eleven books included a series for Rinehart that included Footloose in France (1948); Footloose in Canada (1950); Footloose in Italy (1950); and Footloose in Switzerland (1952). In addition he wrote Confessions of a Grand Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1953); Sutton’s Places (Holt, 1954); Aloha, Hawaii;: The new United Air Lines guide to the Hawaiian Islands (Doubleday, 1967); Travelers, the American Tourist from Stagecoach to Space Shuttle (William Morrow, August, 1980); The Beverly Wilshire Hotel: Its Life and Times (1989).