Stories about underdogs who rise to the top of their chosen field or profession are always fascinating. So how did Adela Breton, an amateur artist, come to produce some of the finest ever copies of ancient Mexican murals and friezes? In several cases, the originals no longer exist or have become badly corroded, and her magnificent drawings and watercolors are the best record we have of these artistic and cultural treasures.

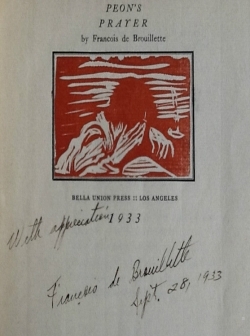

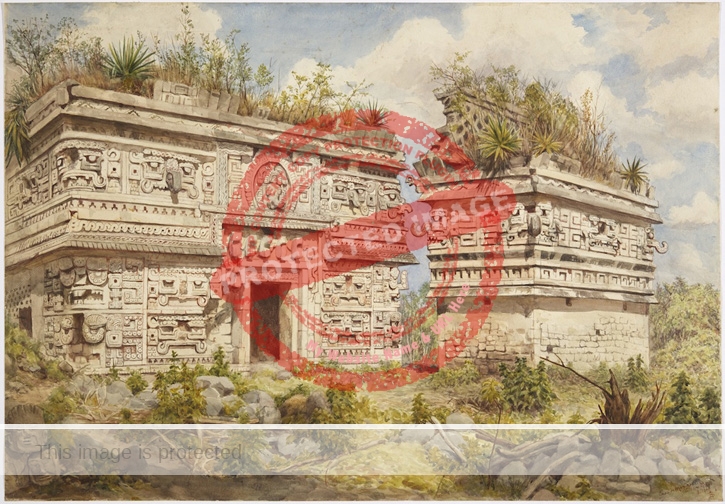

Adela Breton, Watercolor of the east façade of the ‘Nunnery’ at Chichen Itza. Photo credit: Dan Brown/Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives.

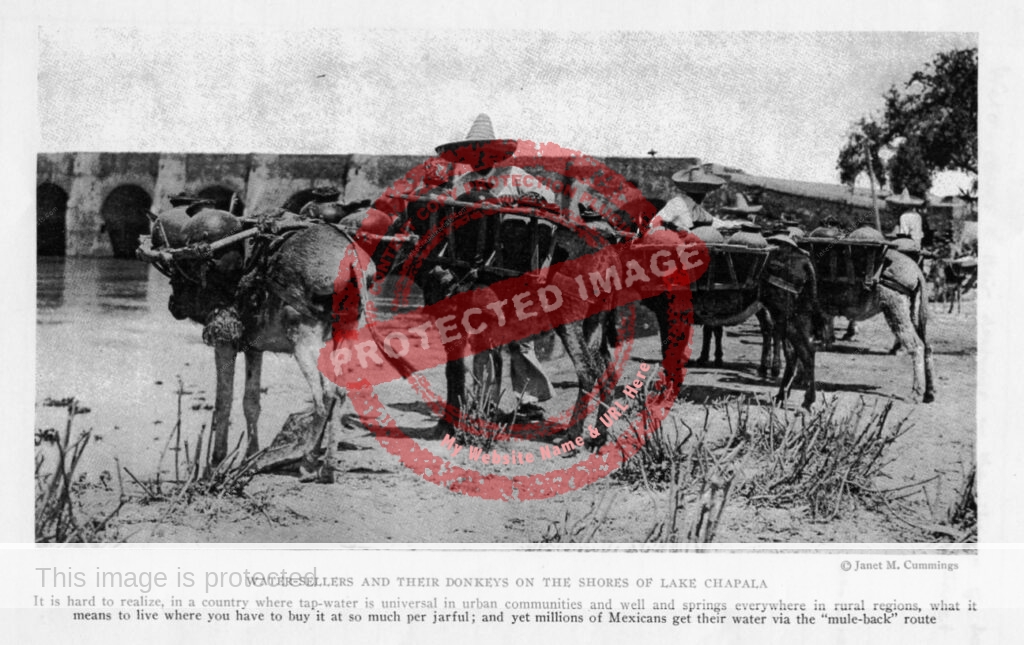

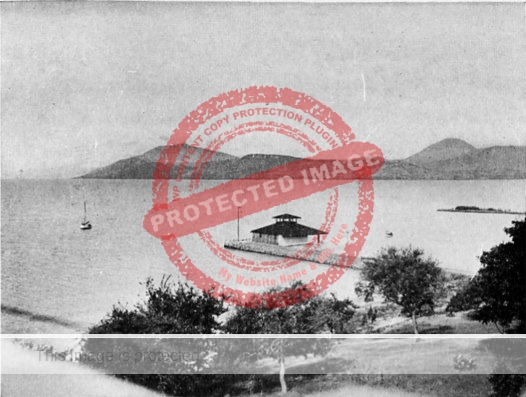

Breton traveled widely throughout Mexico. While her most significant work in terms of archeology was undertaken in central and southern Mexico, she also made a major contribution to the story of western Mexico by recording the excavation of a shaft tomb near Etzatlán, investigating a nearby obsidian works, and by mapping the circular mounds that were the only surface evidence of Guachimontones, the major archaeological site close to Teuchitlán. Breton also visited Chapala, where she sketched a couple of local people and collected several small archaeological pieces.

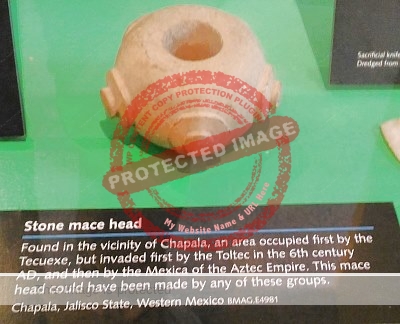

Stone mace head from Chapala. Adela Breton collection, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

We can only speculate as to precisely why she visited Chapala in 1896, but it is more than possible that it was to see if the curative waters would alleviate her rheumatism or arthritis. This is supported by the comment in The Mexican Herald in 1902 that Breton had “for many years spent her winters in Mexico for reasons of health” prior to becoming seriously interested in pre-Columbian civilizations.

It is possible that her introduction to Chapala was at the invitation of Septimus Crowe, a former British vice-consul who had made his home there. It is also very possible that her 1896 visit was a return visit to the lake. The anthropologist Elsie Crews Parsons, who visited in the early 1930s, wrote about the earthenware idolos “washed up from the lake or dug up in the hills back of town” and then writes that “An English lady who visited Chapala thirty-nine years ago quotes Mr. Crow [sic] as saying that the ídolos sold Lumholtz were faked, information that the somewhat malicious Mr. Crow did not impart to the ethnologist.” Breton is the best candidate for this “English lady”. Assuming that Parsons has the chronology correct, then Breton must have visited Chapala and met Crowe in about 1893, well before her proven visit in May 1896. Unfortunately, we may never know for sure since the whereabouts of Breton’s original diaries are unknown.

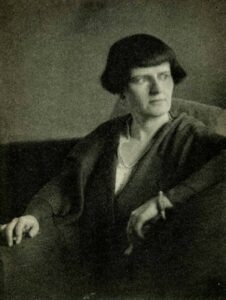

Adela Catherine Breton was born in London, England, on 31 December 1849. Her father, William Henry Breton, served in the Royal Navy, had a keen interest in archaeology and regularly brought curios home from his travels. He also authored two travel books, both published in 1835: Excursions in New South Wales, Western Australia, and Van Diemen’s Land, during the years 1830, 1831, 1832, and 1833 and Scandinavian sketches, or, A tour in Norway.

When Adela was 18 months old, the family moved to Bath and established their home in Camden Crescent. This would remain Adela’s home for the rest of her life. Quite how Adela acquired and honed her artistic skills is unclear. Art would certainly have been an essential part of the general education of any well-to-do young English lady at the time but her proficiency, especially with watercolors, strongly suggests that she had some further art training at some point.

After her mother died in 1874, Adela kept house and cared for her aging father. He died in 1887. Adela was never married, and the death of both parents gave her a substantial inheritance (shared with a younger brother) and enabled her to be independent. Almost immediately, she started to travel, perhaps seeking to avoid British winters and find a climate beneficial for her health. She took to spending extended periods abroad, initially in Canada and the U.S., and then later in Mexico and elsewhere. One of her first trips was to Banff and across the Rockies by the newly completed Canadian Pacific Railway. She also spent time in Japan (1890) and experienced an earthquake in San Francisco (1891) before visiting Mexico for the first time in 1892, when she arrived at the port of Veracruz aboard a ship from Havana, Cuba.

From Veracruz, she then traveled inland via Tlaxcala, Puebla and Cholula to Mexico City. She was so captivated by Mexico that she submitted the first of several travel pieces to her local newspaper back in Bath as “Your Mexican Correspondent”. Her arrival in Mexico City, to stay at the Hotel Iturbide, was duly noted on 1 April 1892 in a Mexico City daily, The Two Republics.

In December 1893, Breton embarked on an extended adventure in Mexico which lasted eighteen months until mid-1895. She traveled into Michoacán, where she came into contact with a local guide, Pablo Solorio, who she employed as her traveling companion and assistant on this and several subsequent occasions. Pablo looked after the logistics (horses, camp sites, food, contacts to local communities) which allowed Breton to focus on recording the local people, architecture, geology and historical sites through her art.

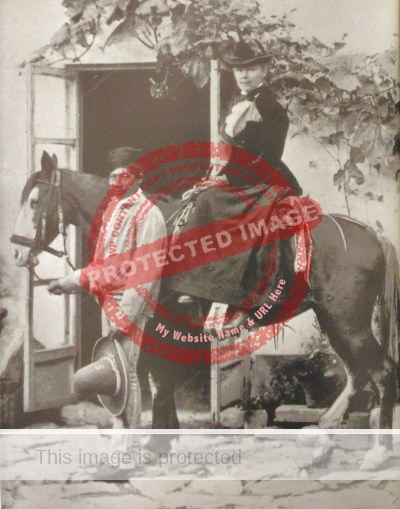

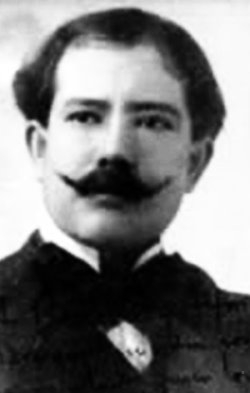

Adela Breton and Pablo Solorio

After Michoacán (and possibly Jalisco), they explored central Mexico and the mountains of Puebla and Oaxaca. Breton’s time at Teotihuacan in 1895 was especially productive since it enabled her to make meticulous sketches and paintings of the pre-Columbian murals of Teopancaxco which became a reference point for many later studies. Breton was also very interested in geology and Mexico’s volcanoes, so both 1xtaccíhuatl Volcano and the Pico de Orizaba were on her itinerary.

Photos taken in Bath show that Pablo accompanied Breton back to the U.K. for a visit, though she makes no mention of this in her extensive notes.

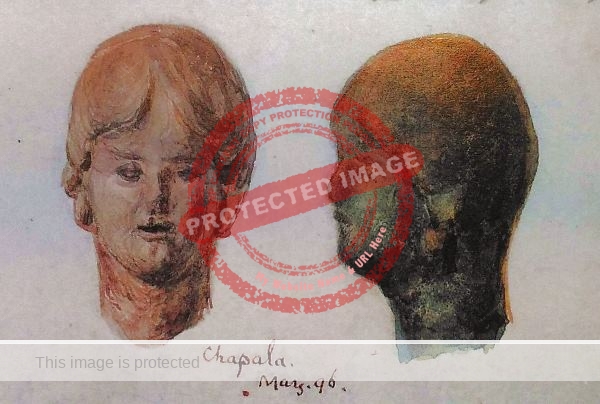

In 1896-97, Adela returned to Mexico and Pablo guided her through Michoacán before traveling north into Zacatecas and south to Guerrero. They visited Chapala in May 1896, as shown by the annotation alongside these two small paintings in her sketchbook for that period. The figurine identified as from Chapala was included in “The Remarkable Miss Breton” exhibit at Bath in 2016.

Adela Breton. Portraits, Chapala. 1896. (From sketchbook)

By the time Breton left Mexico for New York in April 1897, she had apparently become quite a familiar figure in Mexico City with The Mexican Herald reporting that, “Miss Adela Breton, a young lady of this capital, leaves this morning, contrary to the habits of Mexico, quite alone, for New York on a pleasure trip.”

Over the winter of 1898-99, Breton was back in Mexico, painting in the mining town of Real del Monte, a town which probably has more British connections than anywhere in Mexico. Real del Monte attracted Cornish tin miners, and even today, more than century later, residents still peddle their own, spiced-up version of Cornish pasties. Real del Monte is also the place where soccer was first played in Mexico; the local team, formed in 1901, is the oldest in the country.

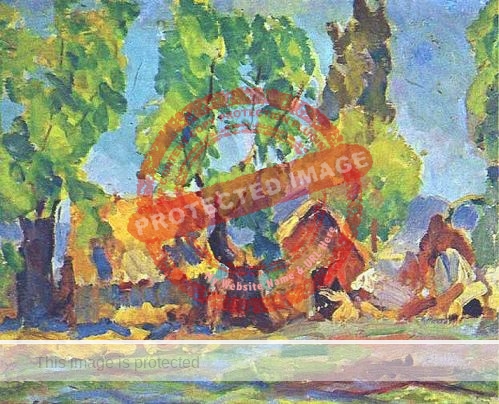

Adela Breton. Watercolor of Valle de Santiago. From sketchbook. Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

The turn of the century marked a new and defining chapter in Breton’s life. She made her first visit to Chichen Itza in 1900, at the age of 50. The visit was at the request of archeologist Alfred Maudslay, who asked her to check the accuracy of drawings he had done himself. Breton was able to improve significantly on Maudslay’s efforts and over the course of the next seven years, spent extended periods of time drawing and paintings at several Maya sites. Some, such as Chichén Itzá and Usmal, were well known even at that time while others, such as Labná and Acanceh, were (and to some extent still are) largely unknown.

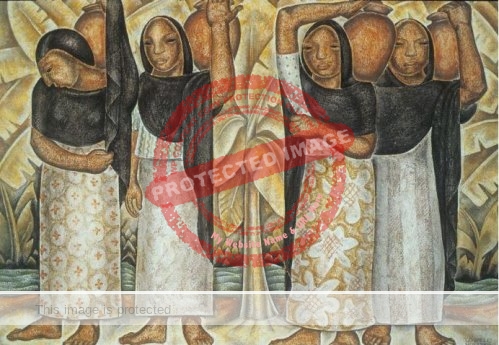

Among her best-known watercolors are those depicting the frescos of battle scenes in the Upper Temple of Jaguars at Chichen Itza. They were already deteriorating by the time Breton painted them, but her record, compiled over numerous visits, is the only one to show all of them as they appeared at that time and in full color. When color photography made its debut, there was very little color remaining on any of the original frescoes.

Breton was constantly worried about the inherent problems of making accurate detailed drawings of such large objects. Despite being an accomplished photographer, she decided, after some experimentation, that even the best photos lacked some of the contrast and details she could incorporate into her drawings following a prolonged study of the real objects. Over the years, Breton justifiably acquired a reputation as one of the finest copyists of Mexican murals, manuscripts, maps and codices ever known.

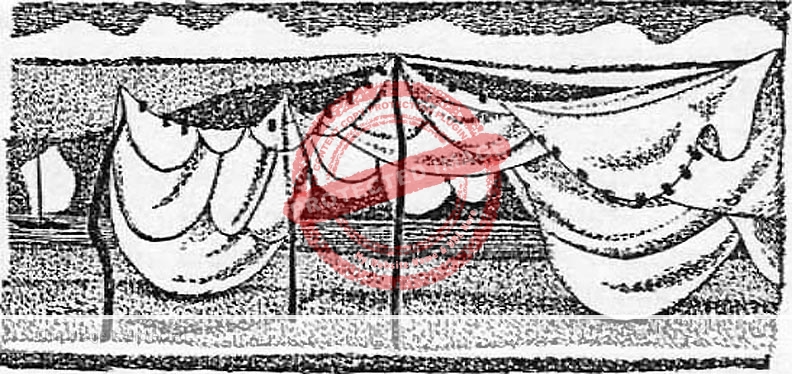

Adele Breton. Freize at Chichen Itza (detail)

Her success was only possible because Breton had not only acquired some fluency in Spanish but was also able to communicate in several Mayan languages. This was essential, given the remote places where she often worked. As a reporter for The Mexican Herald wrote, Breton had chosen to explore ruins “reached only at the expense of tremendous hardships in the way of travel and accommodations” before adding, appreciatively, “and has done it all at her own expense.”

Her long-time guide-companion Pablo died (possibly of yellow fever) in 1904. Adela did not learn of his death for several months. Even though they had no romantic involvement, Adela was distraught when the news finally reached her, but it did nothing to deter her from continuing to document ancient sites.

By this time, Breton knew all the great names in Mexican archeology, including like-minded foreigners such as Zelia Nuttall, Alfred Tozzer, Fredric Ward Putnam, Alfred Maudslay and Eduard Seler, as well as many Mexicans working in the field.

Archaeologist Alfred Tozzer described Breton as:

“a character … an English maiden lady of much means. Her appearance is typical of an independent, unmarried spinster of fully sixty, tall, thin, and with a long face, grey hair, extremely near sighted but straight as an arrow. She wore a short skirt, a dark blue shirtwaist with straight collar attached, and a brimmed straw hat covered with flowers and planted perfectly square upon her head, but the surprise comes when she starts to talk. She is En-glish, you know, En-glish to the very bone and her speech is as exaggerated as any affected English lady ever heard upon the stage.”

Others who met her were less complimentary. For example, Edward Thompson, who was U.S. Consul to the Yucatán while Breton was working at Chichen Itza, wrote, “To tell the honest truth she’s a nuisance. She is a ladylike person but full of whims, complaints and prejudices.”

Breton certainly had several run-ins with authorities during her trips and appears to have regularly bemoaned the food, especially, once writing that, “The difficulty of going into Mexico is the impossibility of getting any food … I used to live chiefly on air and a few peanuts for the long riding journeys – 30 miles without any breakfast, and then some frijol broth”.

Despite such issues, however, Breton always maintained, like so many other foreign visitors before and after her, that Mexico held a very special place in her heart, so I prefer to assume that her occasional moans were more due to her general ill-health, compounded by repeated bouts of malaria and other diseases, than they were to any genuine dissatisfaction.

Her academic respectability grew as she became ever more involved in the biannual International Congress of Americanistas. At the 1902 Congress, held in the U.S., she exhibited her large copies of Mayan mural paintings found at Chichen Itza. In Vienna at the 1908 Congress, she gave a paper about the survival of ancient ceremonial dances (such as Las Voladores) in Mexico.

During the 1910 Congress, held in Chile and Argentina, she presented a paper (with lantern slides) entitled “Painting and sculpture in Mexico and Central America”. She opened this paper with a fervent plea for the world to recognize the quality of indigenous art and architecture in the Americas:

“Not many years ago it was the custom to depreciate the ancient peoples of America, and to represent them as savages, or as best as semi-civilized, with little knowledge of the arts … The excavations of each season now bring fresh evidence of the high rank reached by some of the ancient races in every line of art, and especially their remarkable skill in painting and sculpture. In their conception of grand and impressive buildings and the decoration of them with painted sculptures and frescoes, and still more in their skillful treatment of the difficult processes of colored relief in stuccoes, they take a foremost place among the nations of antiquity.”

The 1912 International Congress of Americanistas was held in London, England, and Breton was one of the co-organizers.

Figurine from Chapala, Adela Breton collection, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

What makes her trips to Mexico so remarkable is not that she was English, or a woman, or both, but that she was a woman often traveling on her own, riding more than a thousand kilometers side-saddle in the process. This is very different to an earlier Englishwomen, Rose Kingsley (daughter of Charles Kingsley), whose 1872 visit to Mexico (South by west or winter in the Rocky Mountains and spring in Mexico) was as part of a large group led by the influential railroad entrepreneur General William Palmer.

Breton’s last visit to Mexico came in summer 1908 when she went to Mexico City to copy an ancient, and fragile, map for Professor Alfred Maudslay. By 1910, the Mexican Revolution was underway and for most of the following decade foreigners were well-advised to stay away from any off-the-beaten-track places of the kind that most interested Breton.

Major archaeological sites which Breton had drawn or painted include Teotihuacan, Chichen Itza, Acanceh, Zempoala, Ake, El Tajin, Mitla, Uxmal, Xochicalco, Cholula, and La Quemada. Her keen eye for detail meant that Breton became critical of many of the so-called “restoration” efforts carried out during the late Porfiriato at sites like Teotihuacan, Xochicalco and Mitla.

In 1922, Breton left her home in Bath for the last time, to sail to Rio to attend the Americanists’ Congress. Ill health caused her to stay longer than she anticipated there, to recover from dysentery, before setting off for home via the West Indies and Canada. Unfortunately, she fell ill again, and died in Barbados, at the age of 73, on 13 June 1923.

She left her entire collection to the Bristol Art Gallery & Museum of Antiquities. It includes more than 300 watercolors and 80 printed photographs, as well as 13 sketch books and has not been on public display very often. The major exhibitions include Bristol (1946), Cambridge (1952), the British Museum, London (1973) and one entitled “The Art of Ruins: Adela Breton and the Temples of Mexico”, which began at Bristol Museums in 1989 and then toured the U.K. Two complementary exhibits were held in the U.K. in 2016-2017: “The Remarkable Miss Breton” (in Bath) and “Adela Breton: Ancient Mexico in Colour” (in Bristol). The most significant exhibit in Mexico of Breton’s work was held in 1993 at the National History Museum (Museo Nacional de Historia) in Chapultepec Castle.

Breton’s remarkable drawings and watercolors of landscapes, people, murals and cities remain an invaluable resource and surely more than merit a permanent display somewhere. Come on sponsors! Make sure this extraordinary female artist-explorer and her work get the attention they so richly deserve!

Sources:

- Breton, Adela C. 1892. “A Mexican Sanctuary”. Bath Chronicle, 14 July 1892.

- Breton, Adela C. 1903. “Some Mexican portrait clay figures”, Man, vol 3, 130-133, 1903.

- Breton, Adela C. 1908. Survival of Ceremonial Dances among Mexican Indians. Proceedings, 16th International Congress of Americanists (Vienna), 531-540.

- Breton, Adela C. 1912. Painting and Sculpture in Mexico and Central America. Proceedings, 17th International Congress of Americanists (Buenos Aires, 1910), 1, 245-247.

- Giles, Sue and Jennifer Stewart (eds). 1989. The Art of Ruins: Adela Breton & the Temples of Mexico. City of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

- McVicker, Mary F. 2005. Adela Breton, A Victorian Artist amid Mexico’s Ruins. UNM Press.

- Pint, John. 2016. “Adela Breton, 19th century British artist and explorer of Mexico feted in England”, Guadalajara Reporter 11 August 2016.

- The Mexican Herald : 10 April 1897, p8; 25 October 1902.

- The Two Republics (Mexico City) : 1 April 1892.

- Townsend, Richard F. (ed) 1998. Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past. Art institute of Chicago.

- Weigand, Phil C. and Eduardo Williams. 1997. “Adela Breton y los inicios de la arqueología en el occidente de México”. Relaciones (Zamora, Mich.), vol 18, #70, pp 217-255

Sombrero Books welcomes comments, corrections or additional material related to any of the writers and artists featured in our series of mini-bios. Please email us or use the comments feature at the bottom of individual posts.

Harry Alverson Franck (1881-1962) was one of the foremost travel writers of the first half of the twentieth century, often taking temporary employment to help finance the next stage of his trip. Franck was a prolific writer, turning out some thirty travel books in a very productive life, including volumes on Mexico, Spain, Andes, Germany, Patagonia, the West Indies, China, Japan, Siam (Thailand), the Moslem World, Greece, Scandinavia, British Isles, Soviet Union, Hawaii and Alaska.

Harry Alverson Franck (1881-1962) was one of the foremost travel writers of the first half of the twentieth century, often taking temporary employment to help finance the next stage of his trip. Franck was a prolific writer, turning out some thirty travel books in a very productive life, including volumes on Mexico, Spain, Andes, Germany, Patagonia, the West Indies, China, Japan, Siam (Thailand), the Moslem World, Greece, Scandinavia, British Isles, Soviet Union, Hawaii and Alaska.

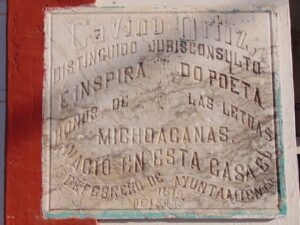

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.

The protagonist of this novel is a young man, Claudio Oronoz, who considers himself an artist. (His poems appear at intervals in the novel). At the age of twenty-one, Claudio evades the obligations and responsibilities foisted on him by his family, who want him to enter business, turns his back on materialism, and heads for the capital city in search of like-minded bohemian individuals with whom he can share his thoughts, feelings and concerns. Thus begins his “odyssey of pleasure”, which subsequently involves trips to the theater, dinners, “parties and orgies”.